Airlines have taken harsh restructuring measures to curb cash outflows

Airlines have been forced to adjust their costs down to their much lower levels of revenue to mitigate the risk of running out of money and going out of business. The Q1 earnings announcements of major airlines revealed restructuring measures including:

- Grounding of planes: In March and April, Cathay Pacific, for example, cut capacity by -65% while United Airlines reduced international schedules to Asia and Europe by -20%. European airlines, such as Ryanair, Lufthansa, EasyJet and British Airways, also stepped up flight cancellations to reduce capacity, slashing more than 400 flights last month to countries including Italy, Germany and the U.S. It is estimated that up to 75% of the world’s overall fleet could have been grounded as a result of Covid-19 travel restrictions over the two-month lockdown period.

- Vouchers for future travel instead of refunds for cancelled flights: Total refunds still to be paid by airlines were estimated at around USD28bn as of May. It’s no surprise that most airlines have urged the European Commission to temporarily suspend the law granting customers full refunds for cancelled flights.

- Temporary furloughs: Several airlines have responded to the crisis by imposing unpaid leave and freezing pay to employees. In February for example, Cathay’s CEO asked its near-30,000 workforce to take unpaid leave on a voluntary basis to help the airline preserve its cash. About 100,000 workers at the four largest U.S. carriers (American, United, Delta and Southwest airlines) were asked to take voluntary unpaid or low-paid leaves.

- No dividends or stock buyback programs: The strings attached to the USD50bn aid package enacted to help America’s stricken airlines have forced major U.S. carriers into ceasing any stock buybacks and dividends, their main channels for rewarding investors, which has made their shares less attractive. Other major carriers around the world face the same situation.

The measures taken to withstand the current storm in a longer-term context are equally severe:

- Massive lay-off plans loom ahead: Airlines are running up losses partly because they can’t furlough or cut their staff more deeply than their bare-bones flight schedules. So, permanent cuts in the well-paying jobs found across the air sector are inevitable and coming soon. British Airways has already planned to remove around 30% of its workforce, while Ryanair could lay off 3,000 employees - mainly pilot and cabin crew jobs - starting next July if Covid-19 restrictions continue to batter the travel industry. In the U.S., deep job cuts are coming after October 1 as the federal bailout for the airline industry covers around two-thirds of overall labor costs through September. Estimates suggest that up to a third of the sector’s jobs - roughly 750,000 pilots, flight attendants, baggage handlers, mechanics and others - could disappear.

- Postponements of rents to aircraft lessors: Airlines who lease aircraft have approached their lessors for rent or loan payment holidays or waivers in order to preserve cash. Some airlines are looking to enter into loans or sell assets quickly in order to raise cash, for instance by the sale and leaseback of aircraft. Most lessors and banks have sought to work with their airline customers and agree to rent holidays or the restructuring of payments. Indeed, if the fundamental business of an airline is sound, it is better in the long term to ensure an airline’s survival than to risk its failure and to have to go through the process of repossession, which typically results in losses such as rent arrears and transition costs. In any event, many lessors consider that it makes little sense taking back aircraft at a time when demand is low, and placing them at all, let alone at a similar rental, will be difficult. More broadly, younger, fuel-efficient narrow-body aircrafts are best positioned to be key for airlines and lessors post-pandemic.

- Delays (if not cancellations) in new aircraft orders: This has been the main transmission channel through which airlines’ hardships have passed on to upstream aircraft manufacturers. Boeing and Airbus have been forced to temporarily suspend or slow production at many facilities as a result. For example, the A320 production rate has been reduced to 40 aircraft per month, down from an average of over 53 aircraft per month in 2019. The A330 and A350 programs are reduced to a rate of two and six aircraft per month, respectively. Turning to the orders race, Boeing reported 31 gross orders in March and 150 cancellations for a total of -119 net new orders. Year-to-date, Boeing has accumulated 49 gross orders (196 cancellations, -147 net new orders). On the other side, Airbus booked 60 gross orders last March and reported 44 cancellations for a net of 16. Year-to-date, Airbus has accumulated 356 gross orders (66 cancellations, net of 290).

- Fuel-hedging optimization: Fuel accounted for about a fifth of operating costs on average at the big four U.S. carriers last year. So Brent priced at USD38 a barrel would lower the cost per gallon of jet fuel for U.S. airlines by as much as 55%, according to Moody’s calculations. The problem this time is that the revenue falls outweigh fuel savings, while airlines that use hedges to lock in fuel costs cannot cash in on lower prices immediately. With no hedging or change in the crack spread, a 20 USD/b lower fuel price could shave off USD65bn from the industry’s 2020 fuel bill, based on our average 41 USD/b oil price forecast. However, many airlines will have hedged 2020 fuel so this benefit could be delayed for some.

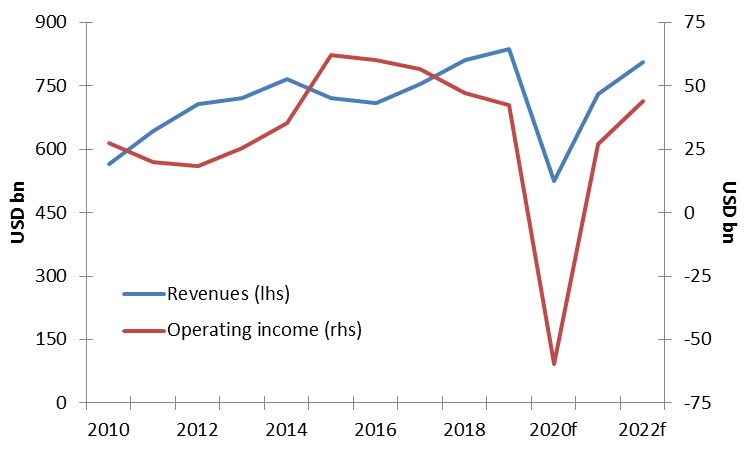

It is very difficult to provide a global estimate of these cost savings for the entire air industry, but available information suggests that they could help airlines hold back cash exits for one more quarter once lockdowns end. Although lower jet fuel prices may provide some offset to airlines’ extra costs to keep running, the collapse in travel demand over the first half of the year will have a huge impact on profitability.

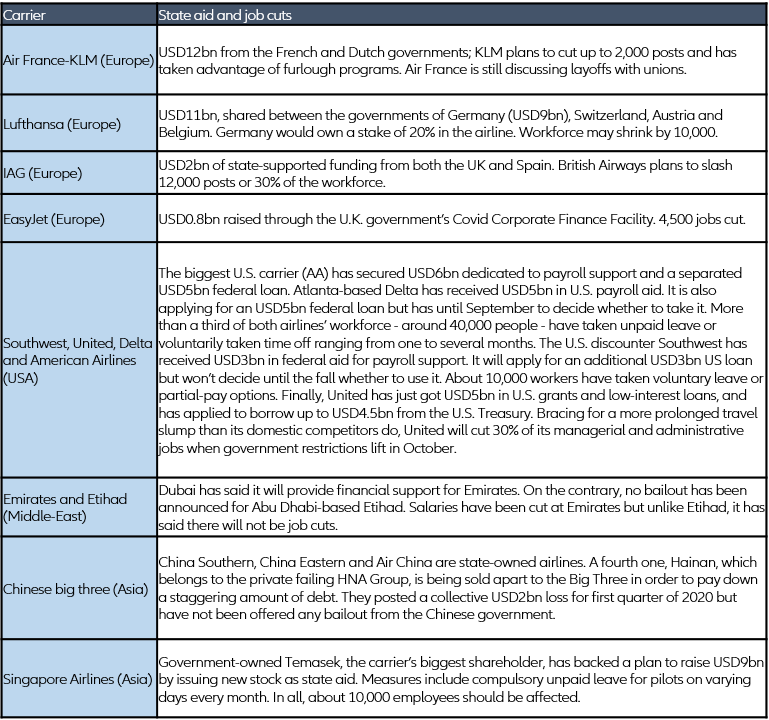

As of mid-May, governments had dedicated USD123bn to propping up the air transport industry (see Figure 5). Year-to-date, public support to airlines can be broken down into loans (USD60bn), employment aid (USD35bn), secured loans (USD16bn) and public funding (USD11bn). However, this support has been distributed unevenly. Unlike Asia, Europe or the U.S., the Middle East and Latam’s airlines have barely benefited, with public support accounting for less than 5% of airlines’ yearly revenues. This partially explains why two of the largest Latin American airline companies (AVIANCA, LATAM) recently filed for bankruptcy. They did not receive support mostly because air transport in the region is positioned as a luxury good for people who usually prefer road transport.

The U.S. government struck first with its Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act, better known as the CARES Act. It has provided a total of USD50bn in assistance for passenger carriers, split between a USD25bn Payroll Protection Grants package and a USD25bn Loan and Loan Guarantees facility. This represents 25% of U.S. airlines’ yearly revenues. Europe comes in the second position with public support amounting to 15% of the yearly revenues of airlines in the region. Asia is in the third position, with public support accounting for 10%.

The massive scale of state support raises concerns about whether the cash windfall is standing in the way of a a necessary thinning out of the sector by supporting weak airlines – among which some are state-owned or flag carriers – that are highly leveraged or unprofitable.

Figure 5: State-aid and layoffs for global airline companies