Regional Outlooks

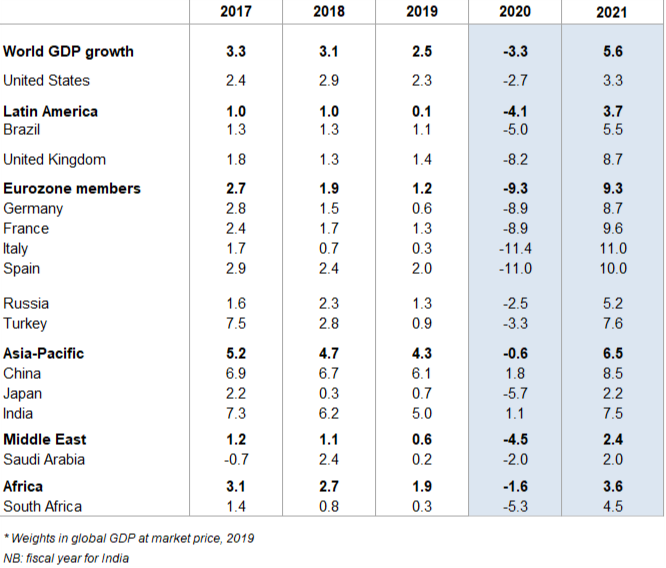

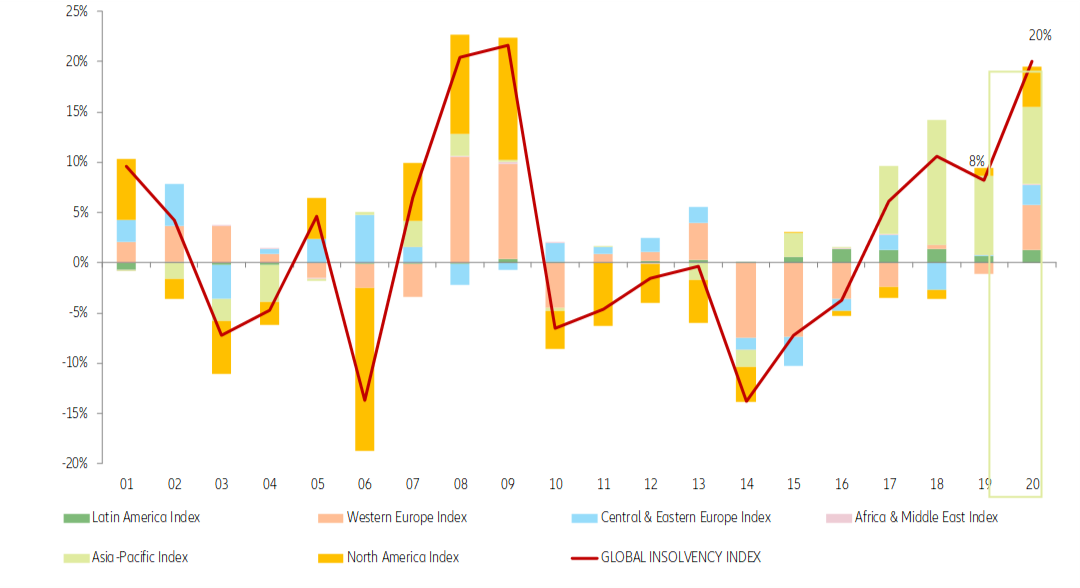

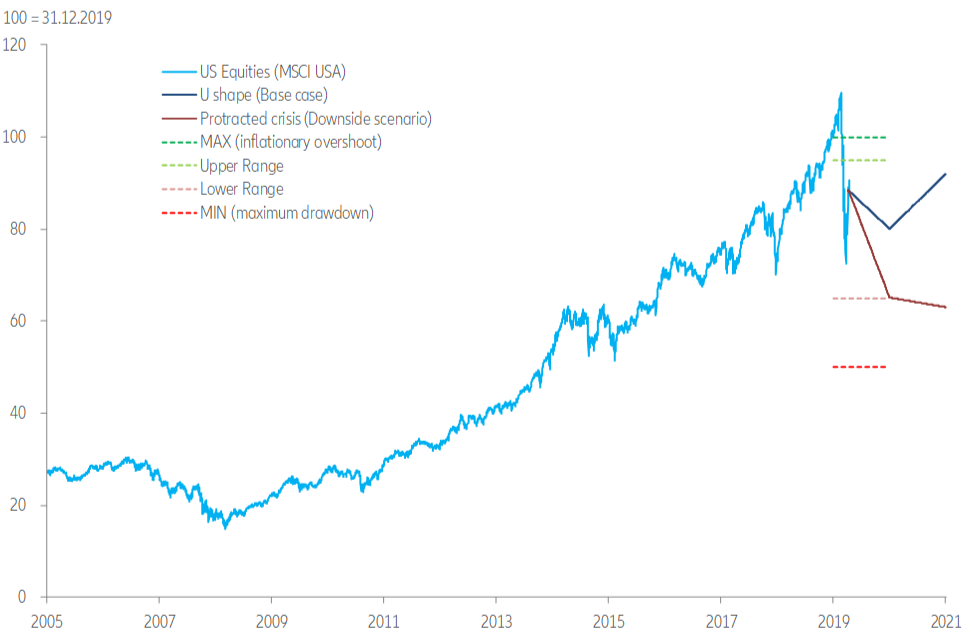

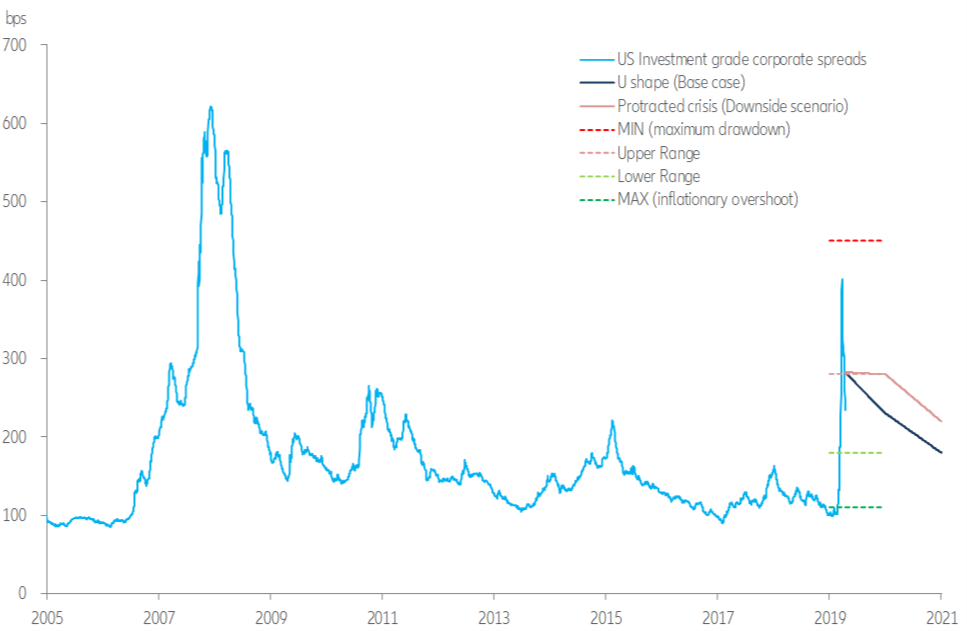

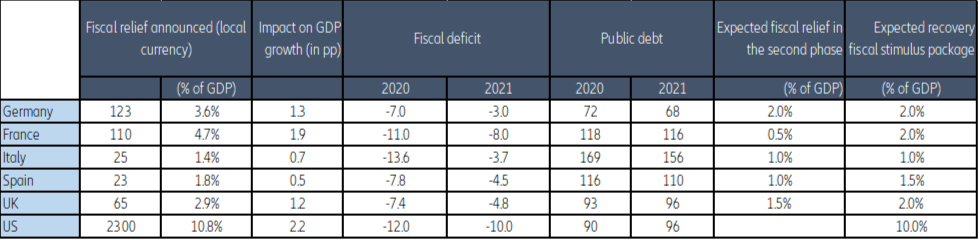

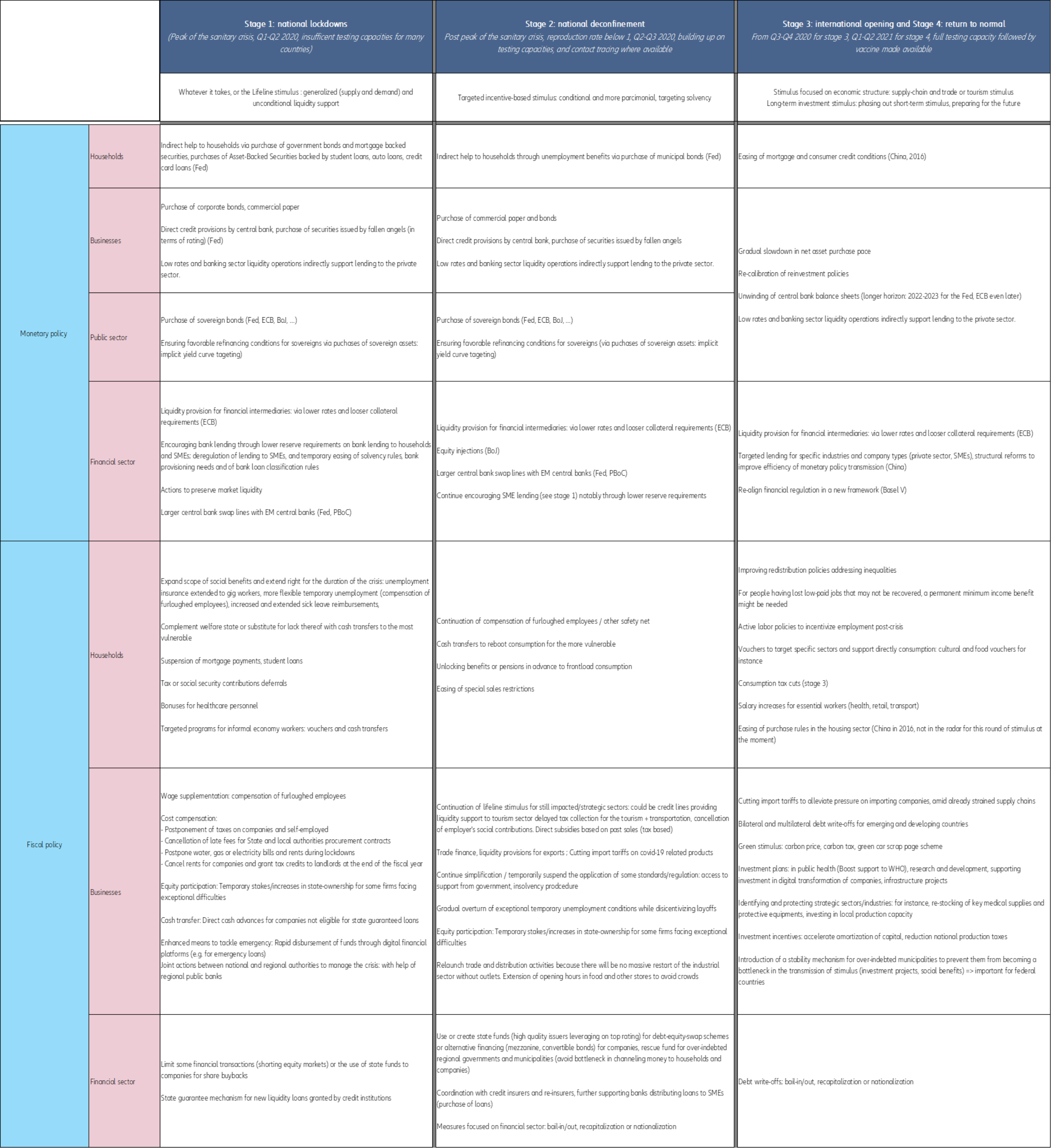

In the U.S., a rather short duration of the lockdown and bazooka policies will limit the impact of the Covid-19 shock. We expect more fiscal stimulus to be announced before year-end in favor of the corporate sector and municipalities, while the announced USD2tn for infrastructure spending program is less certain. The Covid-19 shock was immediately visible in job market conditions: initial unemployment claims jumped to a historical high of 22 million people in the two last weeks of March and two first weeks of April, which is likely to elevate the unemployment rate from 4.4% to 13.5% before year-end. In terms of growth, this kind of adjustment would mirror a significant decline of growth from +2.5% y/y in Q4 2019 to a trough of -8.6% y/y in Q2 2020 (-30 q/q annualized). In these circumstances, U.S. GDP growth would contract by -2.7% y/y in 2020 compared with its growth of +2.3% y/y in 2019. This represents a significant downward correction compared with our prior scenario for 2020 of +0.5% y/y. Our sensitivity analysis had already identified the fact that switching from a one-month to a two-month confinement (social distancing in the U.S.) was enough to anticipate a much lower level of growth (close to -2% y/y). We now anticipate two months of social distancing and a delayed de-confinement, meaning that the U.S. would return to its “normal” level of activity prior to the Covid-19 crisis only in the middle of Q4 2020 or beginning of 2021. This scenario is likely to translate into a significant rise in the delinquency rate of industrial and industrial loans to 6.5% at the end of the year, compared with 1.1% before the crisis. This is equivalent to an expected increase of insolvencies by 25% y/y, compared with 7% in our previous estimate. Amid mounting economic difficulties, the U.S. government announced a rapid extension of the PPP (Paycheck Protection Program) program, which was quicklyexhausted, with an additional USD484bn to be soon voted on by the Congress. We expect further stimulus to complete the so-called CARES program (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act (USD 2.3 trillion) and be announced in the coming weeks, in particular in the direction of states and big municipalities. A big infrastructure stimulus, amounting to USD2trn could be announced later, albeit with a certain delay and lower probability as bi-partisanship is less established in this area (we don’t integrate it in our scenario for now). We estimate at USD500bn the supplementary mattress of stimulus policy to be announced before year-end and prior to a potential infrastructure program.

The Eurozone economy will take a year to recover to pre-crisis levels. The domestic shock accounts for 30% to 40% in countries where confinement is very strict such as Spain, Italy, France and the UK. A two-month confinement period, coupled with a very gradual easing of containment measures, will push the European economy into the sharpest recession since WW II. We expect GDP growth to contract very strongly in H1 2020 (-4% q/q to -8% q/q in Q1, and from -10% to -20% q/q in Q2 depending on the country). The gradual easing of containment measures in several countries from early May onwards will set the stage for a marked – albeit to a large extent technical – GDP rebound in H2 2020. Already announced deconfinement plans suggest that controlling measures (mandatory face masks in supermarkets and public transport, a prolonged ban on events till at least end-June and targeted containment, consisting of isolating infected persons, testing suspected cases and tracking infections) will remain in place for several months to minimize the risk of a renewed surge in infections (see Exiting the lockdowns – A tale of four stories). Moreover, de-confinement at first will largely concern the domestic economy. As a result, we expect the EU single market to remain impaired by border restrictions until early 2021. Meanwhile, external EU border restrictions – in particular against countries that are less capable of containing the virus outbreak or that are pursuing a herd immunity strategy – could well remain in place throughout 2021 until a vaccine will be in place. Therefore, it should take until early 2021 – i.e. a full year - for Eurozone GDP to recover to its pre-Covid-19 levels. However, in some countries, particularly those that boast a large value-added share in services and tourism, the recovery process could well last until mid-2021 as these sectors may see longer-lasting damage from the crisis. Despite more stimulus expected down the line in an effort to jump-start the economic recovery, European countries look set to contract by close to -9% (France, Germany, the UK) to more than -10% in 2020 (Italy, Spain). We anticipate additional fiscal support during the crisis exit period: from infrastructure spending to electric car scrappage schemes and corporate investment incentives. We estimate that a doubling of current support packages from 2% of GDP could lift GDP growth by 1ppts. The dynamic rebound in 2021 of +8.7% is based on the assumption that a vaccine or an effective treatment is in place that allows for a return to normalcy.

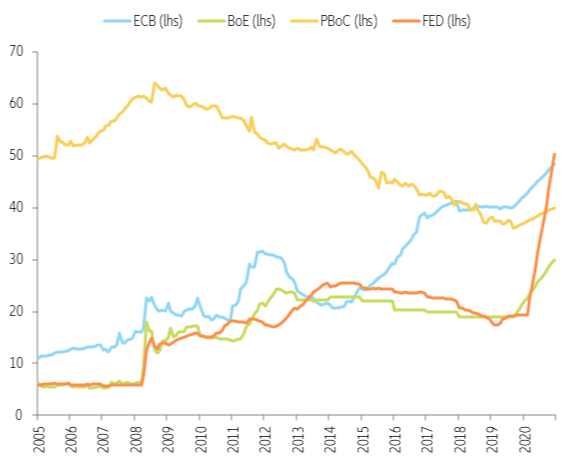

In China, our 2020 GDP growth forecast now stands at +1.8%, revised down from +4.0% (after +6.1% in 2019). We have factored in the impact of the latest Covid-19 news domestically and in the rest of the world: the risk of second waves of outbreaks in China is delaying activity resumption and domestic demand, and confinement measures in place in China’s trading partners is pressuring external demand. High frequency data indeed suggests that production is still 15%-20% below its usual level (even lower for consumption), meaning that resumption is slower than we had expected in early March. We now account for a full resumption of economic activity in June 2020. The recovery of the Chinese economy should become more visible in H2, helped by an accommodative policy stance, particularly on the fiscal side. We expect supportive fiscal measures to account for 6.5% of GDP in total in 2020, after 3.3% last year. Fiscal stimulus is mostly composed of public investment (in infrastructure, health, green policies, technology and other projects) and corporate tax and fees cuts. On the monetary side, the PBOC has injected 2.8% of nominal GDP worth of liquidity, with a particular focus for SMEs. We expect further injections worth at least 1% of GDP. Credit conditions should also be eased further, with the loan prime rate lowered by a further 20bp (after 20bp since the beginning of the year).

The worst is not over in the emerging world. Economic activity in the Emerging Markets has also been choked off by internal and external confinement measures, along with disruptions to supply chains and the dramatic decline in global trade volumes in general. We have therefore slashed our forecasts and now expect EM GDP to contract by -0.1% in 2020. This would be the worst output decline rate since comparable statistics became available, including during the 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis (+0.8% for EM). In our baseline scenario, we assume two months of full confinement on average in major EMs, followed by a gradual lifting of restrictions and a return to pre-Covid-19 output only in early 2021. We forecast a rebound to +5.9% growth in 2021. However, risks associated with the global shock are skewed firmly on the downside. Crucially, EMs have mostly limited and unequal capabilities to fight this pandemic. The lower their capabilities, the longer confinement could last: we find Nigeria, South Africa, Ukraine, Argentina, Romania and India as the most vulnerable. Moreover, EMs have registered record capital outflows since March, triggering very strong currency depreciations and liquidity constraints for the weakest. Should the liquidity crisis turn into a debt crisis, the large EMs most at risk of rating downgrades and subsequent sovereign or corporate defaults are Argentina, Turkey, South Africa, Angola, Mexico, Chile, Ecuador, Pakistan, Indonesia, Malaysia, Romania and Hungary.

In Asia-Pacific, we now expect aggregate growth to decline to -0.6% in 2020. This means that the Covid-19 shock would be larger than the Asian financial crisis (1998 growth at +0.1%). All of the main economies of the region should experience a technical recession in H1 (except for China and India) as confinement measures are being announced and/or extended. Economies seeing (renewed) outbreaks of Covid-19 and more dependent on global trade and tourism are likely to be hit the hardest, including Hong Kong, Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia and Japan. We have also significantly downgraded again our forecasts for Australia and New Zealand, as the countries enter their winter months and confinement measures may not be lifted quickly despite promising downward trends in infections recently. Going into 2021, we expect a recovery in Asia-Pacific, with GDP growth improving to +6.5%. In a downside scenario of a protracted global crisis, GDP growth for the Asia-Pacific region could decline to -9.8% in 2020 and -0.1% in 2021.

In Eastern Europe, annual GDP is forecast to contract by -3.9% in 2020, followed by a rebound to +6.2% in 2021. Open and tourism-dependent economies will be hardest hit by the Covid-19 crisis (e.g. Czechia, Slovakia, Croatia). Romania, Russia and Turkey have relatively weak health systems, potentially requiring longer confinement. Russia (-2.5% in 2020) also faces the sharp drop in oil prices, but is currently pumping more oil than in 2019 (which paradoxically mitigates the decline in GDP growth) and has sufficient fiscal power to withstand the shock for at least a year. Turkey’s growth is forecast at -3.3% in 2020 as it benefits from a good start to the year, but risks are skewed more to the downside than for others, notably because non-financial corporations have large external debt payments falling due in the next 12 months, which is likely to result in payment defaults.

In Latin America, recession is unavoidable and is likely to be the strongest on record, due to a triple shock. The China trade and commodity price shock, the oil price shock and lastly the stronger shock of confinement measures on virtually all economies. Overall, we expect a contraction of around -4.1% in 2020 in our baseline U-shaped scenario, and -8% in case of a protracted crisis. Monetary policy easing will help cushion the blow but won’t prevent recession from happening. Few countries have fiscal leeway (Chile, Peru, Mexico to a lesser extent) so many will have to resort to emergency IMF lending. The countries most at risk are oil exporters, tourist destinations and lower-income Central American countries. The risk of policy mistakes is high in Mexico and Brazil, where political pressure and labor informality render confinement difficult.

The Middle East is facing the twin shock of Covid-19 and the sharp drop in oil prices. As a result, real GDP in the region as a whole is forecast to contract by -5.1% in 2020 in our baseline scenario, before moderately recovering to +2.2% growth in 2021. In our downside protracted crisis scenario, output would plunge by -11.6% in 2020 and fall by another -1.3% in 2021.

Africa has been hit by the Covid-19 outbreak mainly through the sharp decline in commodity prices (oil, cacao, metals and minerals) and the slowdown of trade with China and Europe. The economies, which would be hit the hardest by the decline in oil prices are Nigeria, South Africa, Angola, Gabon, Ghana and Congo. The disruption of tourism activity and the drop in remittances could put the external sector under pressure in Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco and Ethiopia. The region is expected to enter recession in 2020 (-1.6%) and rebound slightly in 2021 (+3.6%).

[1] Unlimited purchases of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities – they had previously been limited to USD500bn and USD200bn respectively; Provision of USD300bn more in new financing to employers, consumers and businesses via a new program to be defined and capitalized by the U.S. Treasury, with USD30bn coming from the ESF (Exchange Stabilization Fund); Creation of two new facilities to support credit to large employers: the PMCCF (Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility), for new bond and loan issuance, and the SMCCF (Secondary Market Corporate Credit) to provide liquidity. Only investment grade companies will be eligible. They will be able to benefit from a four-year financing bridge; Resurrection of the TALF (Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility) to encourage the issuance of ABS (Asset-Backed Securities) backed by student loans, auto loans, credit card loans and loans guaranteed by the Small Business Administration; Municipal bonds with variable rates and banks’ certificates of deposit to eligible for the MMLF (Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility); Extension the securities being targeted by CPFF (Commercial Paper Funding Facility); Creation of a Main Street Business Lending Program to support lending to small and medium-sized businesses representing USS 2,3 trillion. It will offer loans on business with up to 10,000 employees and revenues of $2.5 billion. The total amount available will be $600 billion. It also included $500 billion in loans directly to states and municipalities (not just buying their bonds). It also expanded recently created lending programs by $850 billion

[2] Compared to the new debt to be issued in the coming months by Eurozone governments – and in particular by Italy, where we expect the debt burden to rise close to 170% of GDP this year – the ECB’s EUR750bn Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program is starting to look decidedly less mighty. The four largest economies alone – Germany, France, Italy and Spain – look set to issue about EUR1trillion in long-term debt in 2020. Smaller policy tweaks such as reinvesting PEPP purchases or accepting junk-rated bonds as collateral are likely but will certainly prove insufficient on their own in this context.