Demographic change poses a formidable challenge for Australia: Despite only a modest increase in the old-age dependency ratio, the number of people aged 65 and older will almost double from 4.1mn today to 7.5mn within the next 30 years.

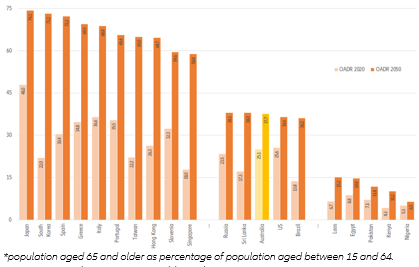

Countries are going to be hit in varying degrees by demographic change, not only in terms of the increase of the shares of older people in their populations but also with respect to the pace of change. According to pre-Covid-19 population projections, Australia’s old-age dependency ratio was expected to increase rather moderately from around 25% today to roughly 38% in 2050. Many Asian countries, notably Japan but also South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore, where the old-age dependency ratio is expected to treble within this time span, and some European countries such as Spain and Italy, will have to cope with old-age dependency ratios almost twice as high by mid-century. However, even this modest increase implies that the number of people aged 65 and older in Australia will almost double from 4.1mn today to 7.4mn within the next 30 years (See Figure 1).

While the Covid-19 pandemic has caused more than 4.1mn premature deaths until July 2021 worldwide , wiping away the life expectancy gains of decades and leading to record-low numbers of births in many countries in 2020, there were no observed effects in the total birth and death statistics in Australia and no reversal of exisiting trends. However, net overseas migration plunged from 247,600 in 2019 to a mere 3,300 in 2020, resulting in a comparatively low +0.5% population increase . If net immigration stays subdued for the time being, Covid-19 could accelerate the aging of the Australian society.

Figure 1: Old-age dependency ratios* in selected countries, in percentage