EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

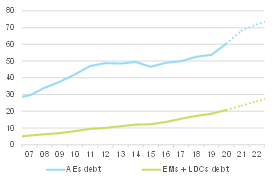

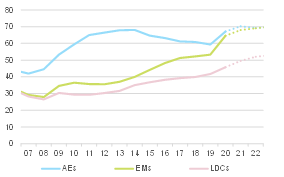

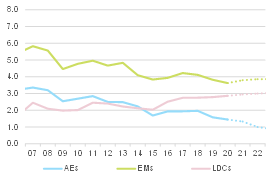

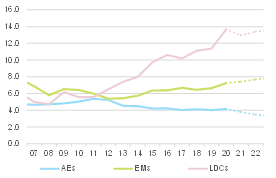

- The Covid-19 pandemic and related global economic crisis triggered an unprecedented shift in public debt sustainability in the developing world. Emerging Markets (EMs) and Low-income Developing Countries (LDCs) have been hit harder by the post-Covid debt surge, reflecting their heavy debt-service burden compared to Advanced Economies (AEs). A decade ago, the share of government interest payments in fiscal revenues was nearly the same (on average around 6%) for the three country categories. Since then, the debt-service cost has fallen for AEs (to 4% in 2020), gradually increased for EMs (7.3%) and more than doubled for LDCs (13.7%).

- Despite the global economic recovery that is already underway (+5.5% in 2021, the fastest recovery in the past 40 years), we expect increased debt distress in EMs and especially in LDCs in the next two years and further sovereign downgrades as well as some defaults. Low-income countries will need a minimum of USD450bn in order to step up their spending response to Covid-19, to rebuild or preserve foreign exchange reserves and to offset the long-lasting scars of the crisis. In the absence of a comprehensive solution, heavy debt burdens may generate a permanent global divergence between rich and poor countries.

- Current debt restructuring initiatives will certainly continue to kick the can down the road and are likely to fall short of their objectives. The IMF’s new USD650bn SDR allocation is a step in the right direction but will be no game-changer. The G20/Paris Club Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) has the merit of including China, for the first time, into a coordinated debt relief initiative. Yet, it will bring only “temporary” relief (i.e. payment deferral without debt cancellation) in 2021 and covers a very small portion of the debt-service burden (excludes EM borrowers and private creditors, for example).

- The changing creditor landscape of public debt (Eurobond holders, China, India and some Middle Eastern countries) has created a “race to seniority” and increased debt sustainability risks. This shift from traditional (concessional) to private and commercial debt complicates debt restructuring and leaves less room for debt forgiveness. China’s collateralized lending with strategic assets gives it a more senior status, for instance in Angola and Zambia, compared to official international lenders (such as the IMF, World Bank). This creates a race to seniority that complicates debt-resolution negotiations in case of repayment difficulties. So far, when things have gone wrong and repayment difficulties arose, countries have bilaterally engaged in debt-restructuring talks with China behind closed doors (Sri Lanka, Ecuador, Angola, Zambia, Kenya), with barely any disclosure on agreed repayment deferrals (rather than write-offs).

- The IMF-coordinated “Common Framework” aims at offering the same restructuring terms for all creditors, including private creditors, by following a “case by case” approach. Coordination, transparency and acceptability will be the main challenges for reaching a satisfactory debt restructuring agreement with all stakeholders. Given the overwhelming share of Eurobond holders, official creditors are currently pushing for private sector involvement in debt restructuring to ensure “fair” burden sharing. Yet, some borrower countries are less inclined to incur losses on private creditors, with the fear of having their sovereign ratings downgraded, which would lead to losing market access. In addition, the success of the initiative hinges on transparent information sharing regarding the stock and conditionality of the debt with China. We believe that the political acceptability of these debt-relief initiatives could be jeopardized should China not take sufficient part in the process. The US and other bilateral creditors may not want to join the initiative if the provided debt relief is used to repay Chinese debt.

- Overall, we expect neither a fundamental blanket solution nor a tsunami of debt defaults in the near future. The international community is likely to step in to bring the needed liquidity relief in case of stress, without being able to offer an overarching solution. Debt forgiveness will bring only temporary financial relief to countries without tackling the root causes of unsustainable debt accumulation. In this sense, proposals like the “New Deal” for Africa from the Paris Summit would offer a viable solution through private-sector-led growth if countries manage to overcome their structural impediments (i.e. high exposure to commodity cycles, weak fiscal revenue collection, inefficient government spending, corruption and poor governance, low potential growth due to shortfalls in human capital, infrastructure and energy investment etc.).

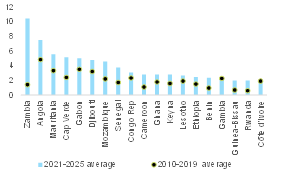

- We identify pockets of sovereign debt stress vulnerability for the next two years. The top 20 riskiest EM countries include the heavyweights Egypt, South Africa, India and Brazil, as well as Pakistan. Our Public Debt Sustainability Risk Score (PDSRS) analyzes sovereign debt dynamics in 61 EMs and 40 LDCs. The countries that we flag as “most vulnerable” have high chances of being next to seek financial support from international lenders, to apply for debt relief/restructuring initiatives or to default on their sovereign debt (i.e. failure to reimburse principal or interest payments in due time). The top 20 riskiest countries include seven economies each from Latin America (Suriname, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Trinidad & Tobago, Panama, Brazil, Argentina) and Africa (Egypt, Zambia, Angola, Tunisia, Ghana, South Africa, Mozambique) and three each from the Middle East (Lebanon, Bahrain, Jordan) and Asia (Sri Lanka, Pakistan, India). However, there is no country from Emerging Europe. The top 20 also includes four of the five countries that defaulted in 2020 (Lebanon, Suriname, Zambia, Argentina).

- The traditional debt sustainability analysis toolbox may not catch all high-risk economies as some specific factors could suddenly trigger severe liquidity tensions followed by sovereign debt defaults, even if the overall debt metrics appear at acceptable levels (the example of Ecuador showed this in 2020). Therefore, we pay particular attention to EMs and LDCs with a high annual interest or amortization burden on sovereign debt and/or with a high level of foreign exchange-denominated public debt along with significant exchange rate vulnerability. This adds Bangladesh, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Iran, Kenya, Malawi, Nigeria, Uganda, Albania, Kazakhstan, Morocco, Congo DR, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan to our watch list for debt distress in the next two years.