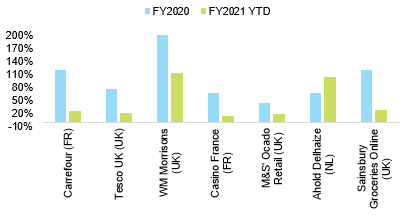

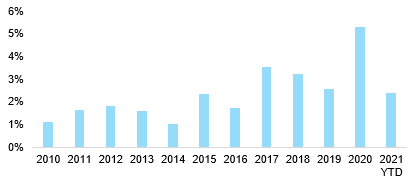

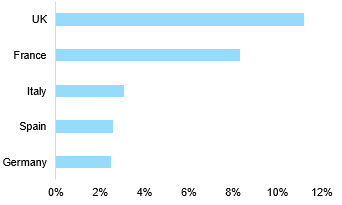

The Covid-19 crisis has fast-forwarded Europe’s e-commerce transition by four to five years, especially in food retail: In the top five markets, e-commerce penetration now ranges from between 3% to 11% of grocery sales. But we estimate that every percentage of grocery sales moving online threatens EUR13.6bn in sales and up to EUR1.9bn in profits (4% of total). More meals eaten at home and the flourishing sales of home and personal care products propelled annual grocery sales growth to +5.3% in 2020, about twice the average growth rates seen in the 2010s (Figure 1). The positive trend carried on in H1 2021, with sales up +2.4% despite a slowdown since March and the progressive reopening of bars and restaurants (Figure 2). In the same period, the use of e-commerce for groceries has skyrocketed and this is expected to continue even as the pandemic is being kept in check on the continent as consumer habits have definitely changed.

Figure 1 – Online grocery sales growth (% change y/y)

Figure 2 – Food retail sales in EU27 (% change y/y)

Figure 3 – Share of online in grocery sales (%, 2020)

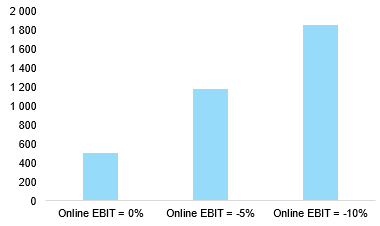

The growing penetration of e-commerce for groceries brings about two main challenges for established retail companies. First, it shakes up the competitive game by creating a new opportunity for retailers to place a greater emphasis on convenience and service vs. price competition. Companies slow or reluctant to embrace the digital transition face the risk of losing market shares. Second, it is a major threat to profitability: Online grocery sales are made at a loss irrespective of the delivery mode (click-and-collect or delivery) using the most common order-fulfillment methods. Grocery e-commerce entails higher costs because part of the service value chain (typically product picking, checkout and delivery) is transferred back from the customer to the retailer while the associated expenses are not fully passed onto service fees. Assuming an average 3.7% EBIT margin for food retailers in Europe (the weighted average of the sector in 2020), we estimate that every percentage of grocery sales moving online is threating a corresponding EUR500m in profits if online grocery margins are at zero, which is optimistic, or EUR1.2bn if they are at -5%. In a more pessimistic scenario, the profit losses could go up to EUR-1.9bn (Figure 4).

Figure 4 – Profits at risk from a 1% sales shift from stores to online (million euros, EU27+UK)

The UK and France are the most at risk. The e-commerce challenge for grocery retailers will play out very differently between countries depending on their respective market structures:

- The UK and France are the most at risk, given the already high penetration rates of grocery e-commerce. Both markets share higher market concentration, as well as the dominance of players historically strong in supermarkets and hypermarkets, and comparatively early to embrace grocery e-commerce. Drive-through click-and-collect services are a distinctive feature of the French market, for example.

- While even more concentrated, the German market is far less mature – local competitors have been comparatively more reluctant to expand their e-commerce operations. This is particularly the case for discounters, whose market share is the highest of all major European countries (35% vs. 10-15% in other large markets) and whose competitive edge was, historically, a low-thrill, low-price retail offering.

- The Italian and Spanish markets have a far more fragmented competitive landscape, with foreign firms (eg. Auchan, Carrefour) competing with national heavyweights and a myriad of smaller, often regional players pooling their purchasing centers. Fragmentation combined with specific national consumer preferences can explain the comparatively lower penetration, but 2020 showed consumer interest was real (online sales increased by 60-65%).

The double threat to market shares and profits will prompt retailers to place their e-commerce operations higher up on their strategic agendas, with three mains areas of focus:

- An adaptation of their store mix and a rotation in investment to adjust for a greater penetration of e-commerce. Because they provide the same “one-stop shop” value as a modern website, supermarkets and hypermarkets are the most at risk of seeing lower footfall and in turn cuts in investment and retail surface.

- Investment in digital capabilities allowing for more efficiency, with a view to reach profit parity vs. physical retail. New capacities added during the pandemic were made with a focus on volumes to serve as many customers as possible in a short period of time, but the return to more sustainable growth patterns should allow for a greater focus on careful planning and profitability. This will call for a redesign of the current logistic infrastructure and the creation of new systems relying extensively on warehouse automation technologies.

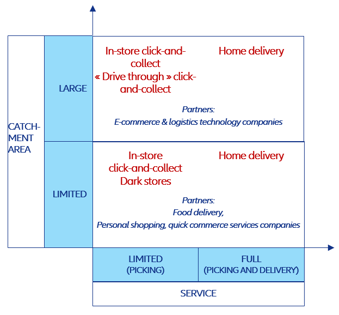

- Partnerships with companies in the fast-growing grocery e-commerce ecosystem. The past few months have seen a growing number of initiatives between food retailers and a fraction of so-called food technology companies including (Figure 5):

- Food-delivery specialists (eg. Deliveroo, JustEat, Delivery Hero etc.) now expanding beyond prepared meals;

- Personal shopping specialists (eg. Everli…) with freelance workers doing the picking in stores and delivery at the customer’s doorstep à la Uber;

- Quick commerce companies (eg. Gorillas, Getir, Cajoo etc.) operating urban dark stores with a generally limited range of products but the promise of super-fast delivery;

- E-commerce logistics services companies offering everything from software to warehouse equipment (eg. Ocado) with a view to provide cost-efficient logistics to established retailers.

Figure 5 – Catchment area and service matrix