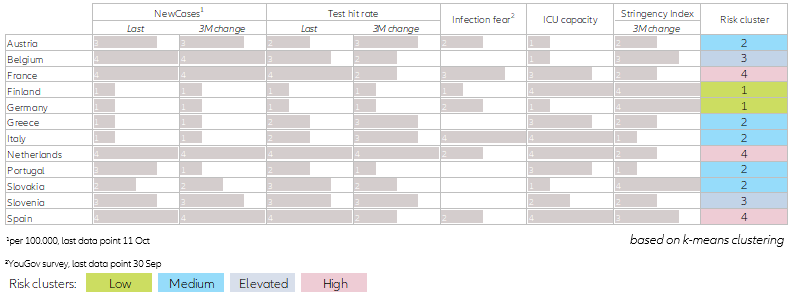

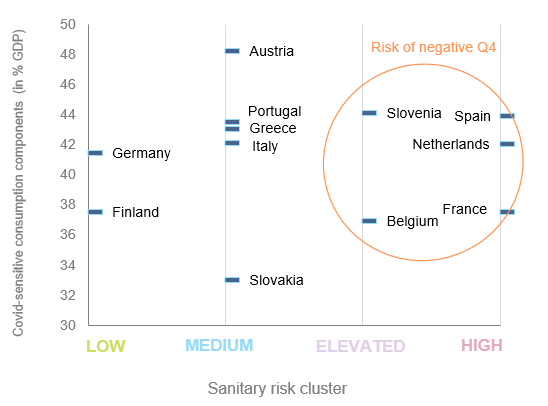

As Covid19-related restrictions are retightened, we expect key European economies to contract again in the final quarter of 2020. We forecast GDP to drop by -1.3% q/q in Spain, -1.1% q/q in France and–1.0% q/q in the Netherlands. Summer ended prematurely for many European countries, with governments reintroducing social distancing measures as the dreaded second wave of infections materialized in August. While all countries in Europe have since seen a rise in cases, our sanitary risk map (Figure 1) shows a wide divergence between best performers (Germany, Finland) and laggards (Spain, France and the Netherlands) who have lost control of the pandemic – again. We see an elevated risk of a double dip recession in countries that are once again resorting to targeted and regional lockdowns. The higher the sanitary risk cluster, the higher the downside risk to Q4 GDP growth (see Figure 2). We already forecast a relapse in both France (-1.1% q/q in Q4 vs. +1.0% previously forecasted) and Spain (-1.3% q/q vs +1.4% previously forecasted). With the fresh containment measures announced in the Netherlands, we now expect also a negative Q4 GDP growth reading (-1.0% vs. +0.5% previously forecasted).

Figure 1 - Sanitary risk map

We estimate the size of the growth setback by estimating (i) the GDP at risk (social spending and recession-sensitive components of consumption) and (ii) the shock of targeted restrictions in the economic centers (e.g. the Paris region, Catalonia and the Madrid region).

Figure 2 – Sanitary risk vs Covid-19-sensitive consumption components

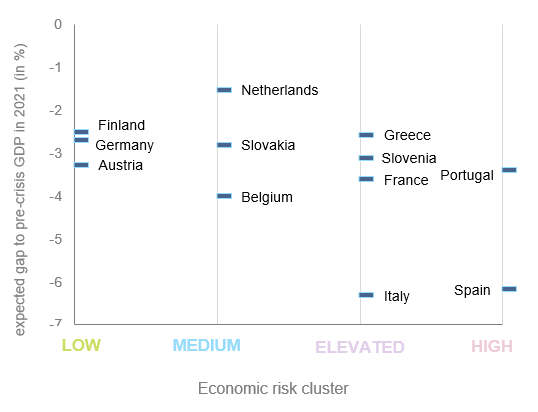

This second wave puts to the test the economic model of key Eurozone countries, returning to pre-crisis levels will take a long time. Spain and Portugal as tourism powerhouses are on the watch list. Indeed, economies that boast a high share of Covid-19-sensitive consumption in GDP, especially spending on services that requires social interaction, and a strong dependence on tourism are most at risk. After all, fiscal policy is proving less effective at boosting confidence here than in manufacturing and construction as long as contagion fears continue to linger. There is therefore a greater risk of long-term scarring. At the same time, those countries with a high level and/or recent increase in unemployment (official or hidden ) will have more difficulties in stabilizing household confidence and reducing the high savings rate. Our economic risk map (see Figure 3), which reflects the interaction of the relevant economic factors, shows that in Germany, Finland and Austria the risks are low, even though in Austria the consumption structure and size of the tourism sector are a weak point. The CEE manufacturing hub (e.g. Slovakia) shows medium risks, as do the Benelux countries. France, together with Italy, is in the elevated risk cluster. We are concerned by the possibility that it might weaken the Eurozone core for a while. This could further undermine policy coordination by fueling economic divergence among member states. Meanwhile Spain and Portugal are particularly vulnerable, given the importance of tourism for their economies, high unemployment and a - so far - timid fiscal policy response.

Figure 3 - Economic risk map

This risk of further economic divergence among Eurozone member states is also reflected in the (expected) GDP gap against the pre-crisis level in 2021 (see Figure 4). Generally, the higher the economic risk cluster of a country, the higher the uncertainty about the strength of the recovery and the higher the probability of an important GDP gap to pre-crisis levels still prevailing at the end of 2021.

Figure 4 – Economic risk vs expected GDP gap to pre-crisis level

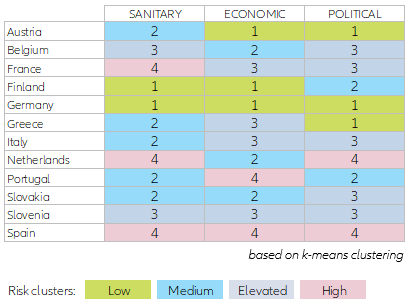

The post-pandemic Eurozone “pecking order”: Solid export economies in the lead (Germany, Austria and Finland), a shrinking core with France’s growth motor (household spending) turning into an Achilles’ heel and Spain as the new Italy. In our political risk map (see Figure 5) we try to gauge the ability of national Eurozone governments to turn the ship around - i.e. to swiftly implement decisive policy measures – by looking at recent approval ratings (including for the handling of the pandemic) as well as the size of parliamentary majorities. Meanwhile, national voting intentions for Eurosceptic parties serve as a gauge of the support for fresh EU policy action. Out of the countries that appeared in the elevated risk cluster, factoring in the political dimension soothes our concerns about Greece and Portugal, thanks to relatively low political hurdles for an adequate policy response. Meanwhile, for countries such as France, Spain and the Netherlands, a constrained political capacity to act risks exacerbating weaknesses in the sanitary and/or economic dimension.

Figure 5 - Political risk map

The risk of an inadequate policy response emphasizes even more the need for fast disbursements from the EU recovery fund. Forget about the legacy clusters that emerged in the Eurozone debt crisis: Following the pandemic reshuffling, the core is still formed by solid export-based economies (Germany, Austria, Finland) but it is increasingly thinning as France looks to exit the Covid-19 crisis clearly weakened and the Netherlands may struggle to put forward an adequate policy response. For the CEE countries, their position as Europe’s manufacturing hub contains economic risks, but they face a major sanitary challenge combined with elevated political risks. Meanwhile, Greece and Portugal still give reason for concern, but Spain is the new Italy having switched from poster to problem child. See figure 6 for the summary of the three risk clusters – sanitary, economic and political - by country.

Spain at a crossroads: ambitious fiscal stimulus, record high political fragmentation

Spain’s political gridlock is only making the sanitary crisis worse, as regional and central governments have failed to agree on a nationwide strategy to curb the second wave. Political tensions on the content of the 2021 budget have also delayed much-needed stimulus measures and reforms that would boost the economic recovery. With the return of targeted lockdowns and strict social distancing to fight rising Covid-19 infections, we expect Spain to see the largest GDP contraction in 2020, far worse than all of its Eurozone peers. We expect growth to contract in Q4. A moderately strict lockdown (50% of that seen in the spring) in Spain’s Madrid and Catalonia regions (40% of Spain’s GDP) should lead to a -1.3% q/q contraction, putting an abrupt halt to the recovery initiated in June.

Spain has recently presented a proposal for a EUR72bn stimulus package (6% of 2019 GDP), in part financed with the EUR140bn it should receive from the EU Recovery fund. This ambitious plan could boost GDP growth by 4.7pp in the next three years. Detailed policies are yet to be announced, but the heavy focus towards public investment (green growth, infrastructure, innovation and education) could yield a higher fiscal multiplier than the stimulus packages of its Eurozone peers. While this is an encouraging step, political hurdles to implementation remain as left- and right-wing parties struggle to find common policy denominators. Parliament could eventually vote a watered-down budget. The risk is for the recovery in 2021 to be only a mechanical rebound, making Spain lag behind its neighbors thereafter.

Fiscal policy: Clearly this is not the moment for complacency. Decisive action across the entire policy spectrum - including health, fiscal and monetary (in that order) - and at both national and supranational level, is urgently needed to keep centrifugal tendencies at bay. Certainly, the ECB will make sure to continue to cap sovereign risk premia, but this hardly qualifies as a sufficient nor sustainable policy response. At best it will help buy time for a meaningful fiscal response to bear fruit. After all, without more structural policy initiatives, an ever more expansive ECB policy comes with risks attached, ranging from mounting financial stability concerns to a rising politicization and in turn loss of independence. The focus must shift from relying on an ECB that is ever “lower for longer” to a fiscal policy that goes for “structurally stronger” by underpinning a credible growth strategy centered on the transition towards a green and digital economy. And make no mistake: given the task at hand, the necessary fiscal policy support will resemble a marathon more than a sprint.

Figure 6 - Risk clusters summary