- The immediate impact of the Covid-19 shock on inflation has been decidedly deflationary, but in light of the brewing cocktail of post-pandemic economic trends, the probability of an inflationary overshoot has also risen. In fact, ambivalent market signals suggest that participants are pricing in a higher risk of extreme inflation scenarios – on both the downside as well as the upside.

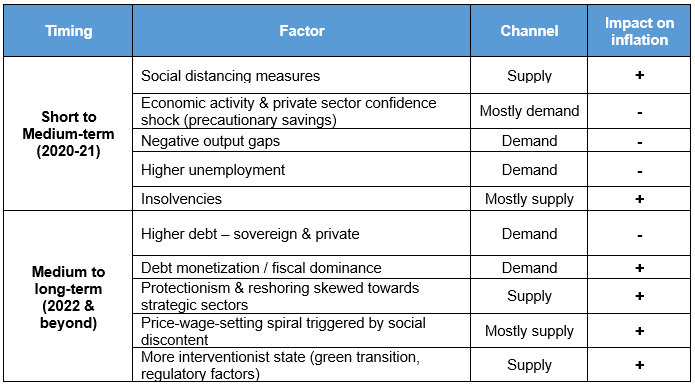

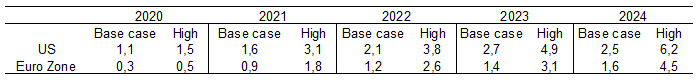

- In our base case, we see the inflation outlook moving through three phases of varying supply and demand pressures: 1) messy data in the immediate crisis aftermath, 2) a disinflationary recovery in 2021 (U.S.: +1.6%, Eurozone: +0.9%) due to substantial slack in the economy and a swift rebound in supply and 3) a temporary inflation overshoot in 2022 (U.S.: 2.1%, Eurozone: 1.2%) following a recovery to pre-crisis activity amid gradual supply headwinds but no policy paradigm change on wages or fiscal and monetary policy.

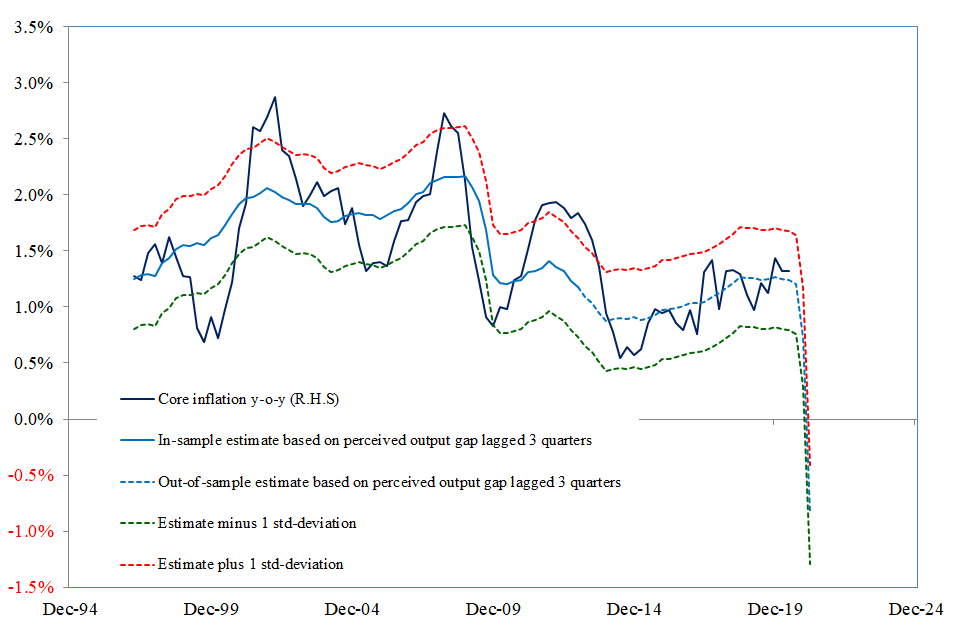

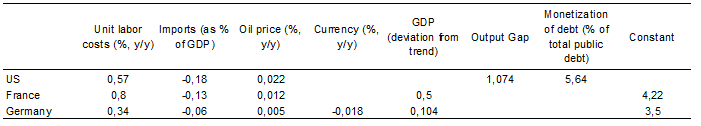

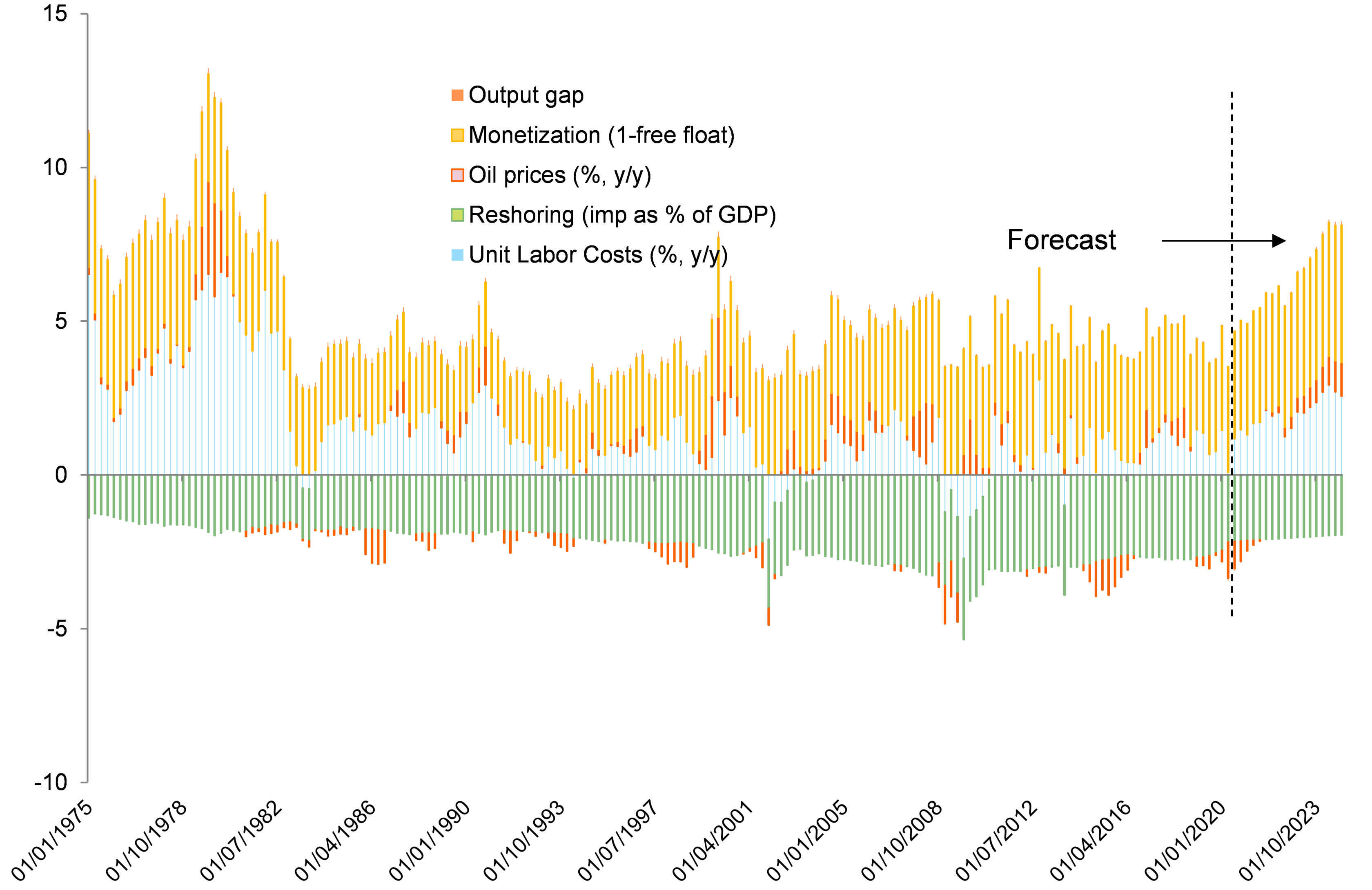

- What would it take for a scenario of a persistently high inflation (probability: 15%) to materialize? We see a risk that supply-side issues, including rising unit labor costs amid weak productivity growth and the extent of the economy’s longer-lasting scarring, could be underestimated. While a 1970s wage-price spiral would be difficult to imagine, given labor unions’ loss of influence, a push for higher wages and more redistribution amid heightened social discontent, together with more state intervention in economic affairs and rising protectionist tendencies, could well exacerbate prevailing supply bottlenecks and lead to a notable and persistent acceleration in inflation. In such a situation, central bank complacency should be particularly monitored. Central banks could indeed be reluctant to engage in an abrupt and aggressive policy U-turn to rein in inflation given (i) a recency bias towards a long period of subdued inflation, coupled with (ii) the U.S. Federal Reserve’s recent strategy switch to Average Inflation Targeting (AIT) and the fear of a major market tantrum. Under such circumstances, our model on long-term inflation projections suggests that inflation could reach 6.2% in the U.S., compared to 4.5% in the Eurozone, by 2024.

Quo vadis inflation?

Following the unprecedented shock experienced earlier this year, the global economy has embarked on an uneven recovery path. But even once GDP recovers to pre-crisis levels, which we don’t expect to happen before 2022, the global economy will have to deal with permanent scarring effects, including lower potential growth, higher debt levels, a larger role of the state in economic affairs and a closer cooperation between fiscal and monetary policy. Regarding inflation, the verdict is still out. In the immediate aftermath of the economic shock, inflation rates across most OECD countries have declined to near zero, but what is the risk that the cocktail of post-pandemic economic trends rings in the end of the low inflation era?

1. AMBIVALENT MARKET SIGNALS

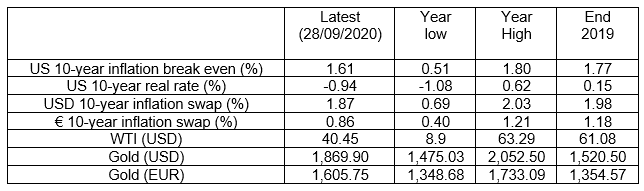

In the wake of the Covid-19 crisis, three recent market developments have (re)ignited a discussion over the inflation outlook. First, inflation expectations – as measured by the breakeven rate on 10-year U.S. TIPS – have risen by 110bp from a year-low of 0.51% to 1.61% (inflation swaps convey the same information). Second, the price of oil (WTI) has jumped from a year-low of USD8.9/bbl to USD40.45/bbl. Third, the price of gold has risen to new record highs in all major currencies: USD1,869.90, but also EUR1,605.75 and JPY197,508.27. However, these increases need to be put into perspective, as they came after sharp declines caused by the Covid-19 crisis.

- At 0.5% on 19 March, market-based inflation expectations were excessively depressed relative to the long-term equilibrium value (1.55%), which we estimate based on the perceived rate of U.S. inflation (2.3%). The labor market (represented by the ISM employment index) and the oil price drive the short-term deviations from this long-term anchor. The reversion to fair value seen since March can be explained by the rebound of the ISM employment index from 27.5 in April to 46.4 in August, as well as by the recovery in the oil price. In contrast, the Philadelphia Fed’s Survey of Professional Forecasters shows that they have cut their 10-year annual-average of headline CPI inflation forecast by about 20bps to 2.03%. If anything, this move was overdue, given the recent behavior of observed inflation and its impact on the perceived rate of inflation.

Figure 1: Market-based inflation bellwethers