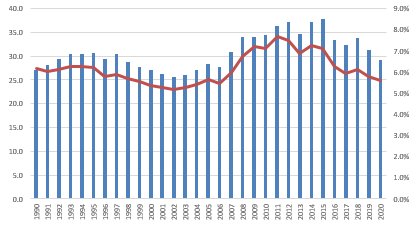

Japan’s life industry as a whole has weathered the long yield winter remarkably well, staying profitable in an environment where interest rates and growth basically disappeared. Yet, we find that there is still some room for improvement within the local market, namely consolidation, even as life insurers start to hunt for growth overseas, mainly in Asia and China, arguably the biggest opportunity in the sector. The end of the bubble economy at the beginning of the 1990s heralded Japan’s long yield winter, which is now in its third decade. From its peak in September 1990 (8.3%), 10-year yields of Japanese government bonds (JGBs) started to decline relentlessly throughout the 1990s (see Figure 1). Eight years later (September 1998), they reached an interim low of 0.8%. Since then, however, they never really recovered, staying continuously below the watershed of 2% and hovering around 0% for the last five years.

Figure 1: JGB 10-year yield, in %

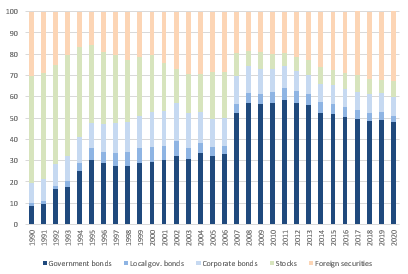

Declining interest rates dragged down investment returns, pushing them in some cases below the guaranteed minimum. At the end of the decade, these negative margins drove some insurers into bankruptcy, representing about 10% of total assets of the life insurance industry. The overwhelming majority of the industry, however, coped quite well with the low-yield environment, which was also compounded by low growth: Over the last three decades, gross written premiums remained basically flat – with a temporary boost by the privatization of Japan Post that increased life premiums by more than 10% in 2007 and 2008 (see Figure 2). Against the backdrop of a deflating economy, however, this is nothing to sneeze at: Penetration (life premiums as percentage of GDP) remained comfortably above 5% and thus much higher than, say, in Germany (3.0%) or the US (3.1%, 2020 each).

Figure 2: GWPs in trillion Yen (lhs) and GWP in % of GDP (rhs)

In 2020, Japan’s life industry recorded a RoE of 11%. Three management levers explain this Phoenix-like rising from the ashes: first, managing the product mix. Protection-type policies such as traditional life insurance and “third sector” products (medical, long-term care insurance) offer better margins, based on mortality and prevalence assumptions, than savings-type policies that are investment-related. Therefore the industry has relentlessly shifted into these products, supported by more favorable regulation, which lifted the ban on life insurers’ participation in health insurance. Since then, life insurers have been able to benefit from high demand for medical coverage (e.g. against cancer), driven by the fact that the comprehensive public health insurance system requires co-payments that can be quite substantial in the case of critical illness. Another area of growth is care products that address Japan’s aging society and changing behavior – older people are increasingly taken care of by nursing homes and other facilities rather than by their own families. Moreover, insurers developed new types of products, e.g. products with wellness benefits, and specialized products, e.g. infertility treatment insurance. In 2020, these “third sector” products accounted for a quarter of all premiums.

Second, managing risks. The mortality tables used by Japan’s life insurers are very conservative. Mortality rates for life insurance policies are higher than actual ones and those used for “survivorship policies” (e.g. annuities) are lower. The result: Payouts are below initially assumed levels. Managing mortality and morbidity risks is key for the profitability of the industry.

Third, managing assets. The most remarkable development is the shift into government debt and the high share of foreign bonds. Life insurers used to be the main creditors of the corporate groups (keiretsu) they belonged to; hence the high share of domestic stocks and loans in the asset portfolio. These times are gone for good (see Figure 3). Today, life insurers channel savings into government debt, helped by a (unique) accounting rule by which JGBs can be classified as “policy-reserve-matching bonds”, exempted from mark-to-market valuation (one reason why insurers shifted toward investment in super-long-term JGBs). At the same time, insurers looked for some extra yield abroad. Were it not for the inclusion of Japan Post in 2007, the share of foreign securities would be already closer to 40% – a share unique to Japan’s life industry. Although around two thirds of foreign bond holdings are currency-hedged, this huge portfolio is not without risk. While these hedges come in the form of short-term contracts, bond holdings are long-term in nature. Thus, Japanese life insurers hold a “rollover risk”, similar to the risks banks are facing in maturity transformation.

Figure 3: Securities by asset classes, in % of all securities

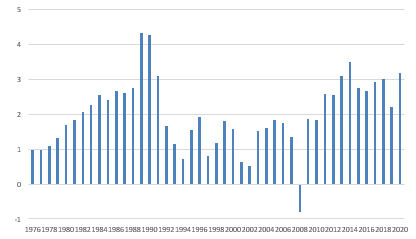

While profits remained in the doldrums in the 1990s and 2000s as several crises (Asian crisis, dotcom bubble, great financial crisis) hit the industry, averaging Yen1.5trn and Yen1.2trn, respectively, they more than doubled in the 2010s to an average of Yen2.9trn, even a tad above the buoyant 1980s (Yen2.8trn, see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Ordinary profit in Yen trillion

Remarkable as this profit comeback is, it does not have to end here: One important lever for improving profitability, namely consolidation, is still mainly absent from current management actions in Japan’s life industry. Back in the 1970s, around 20 life insurers were active in Japan; this number reached 30 at the end of the bubble economy. After a roller coaster development in the 1990s – with many new (foreign) market entries as well as exits – more than 40 life insurers are offering their services in Japan today. The market share of the top five is around 50%. Compared with the situation in the p&c industry – where three players dominate the market and the share of the top five hovers around 85% – Japan’s life industry still seems to have some room to consolidate to reduce costs.

At the same time, Japan’s life insurers have started to hunt for growth in overseas markets, mainly in Asia and China, arguably the biggest opportunity in the life insurance sector. They have recently emerged as big buyers of insurance assets. However, it remains to be seen if this deals spree pays off in terms of profitability. To start with, prices for insurance assets, particularly in the growing Asian markets, are not cheap. And the track record of Japanese companies in integrating foreign businesses has not been too impressive so far. Therefore the risks of overpaying and underperforming cannot be denied. But with a stagnating home market, Japanese life insurers have virtually no other choice than expanding internationally.