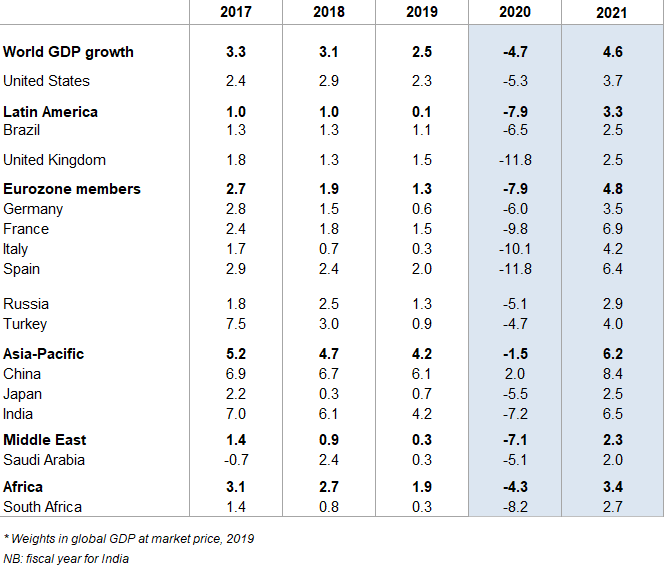

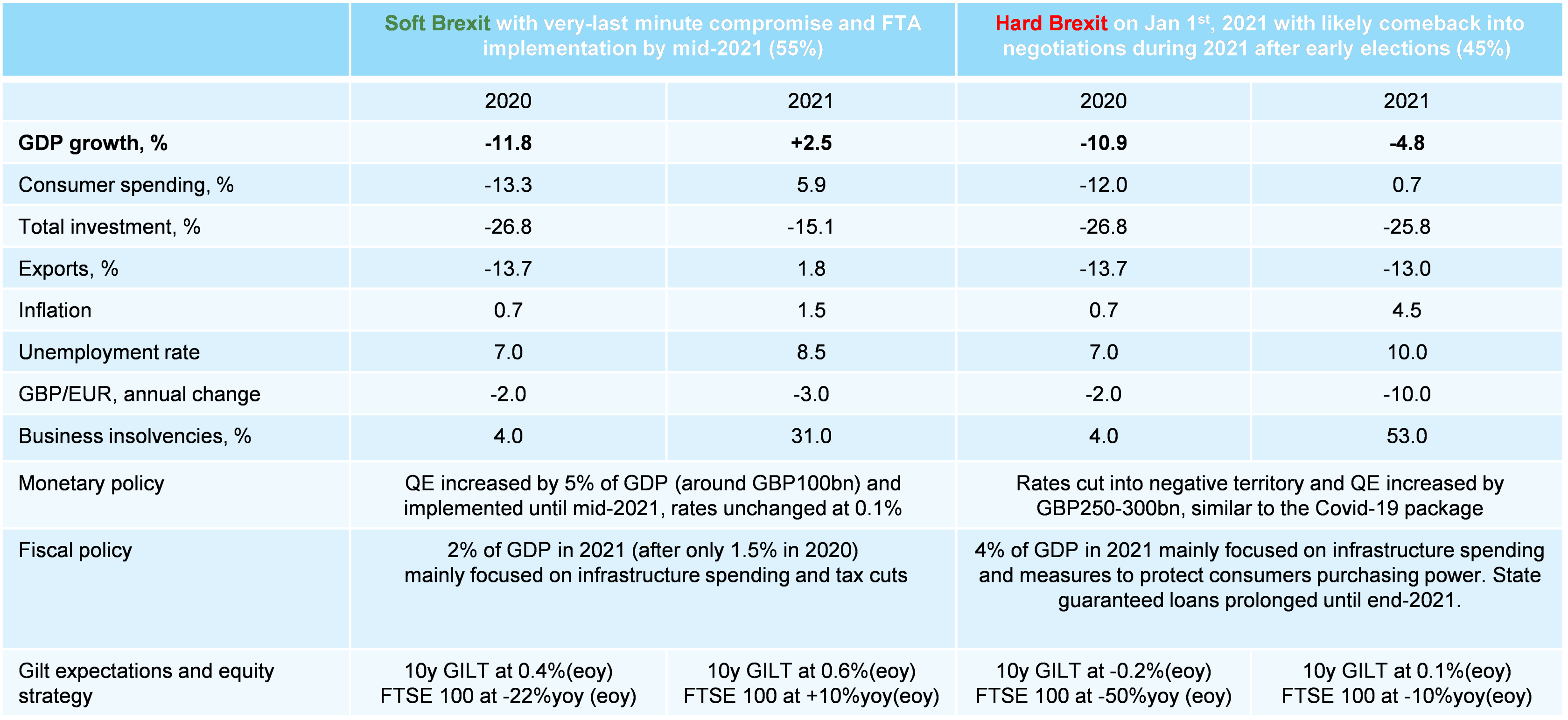

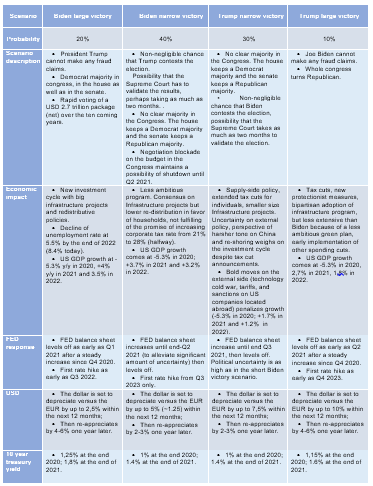

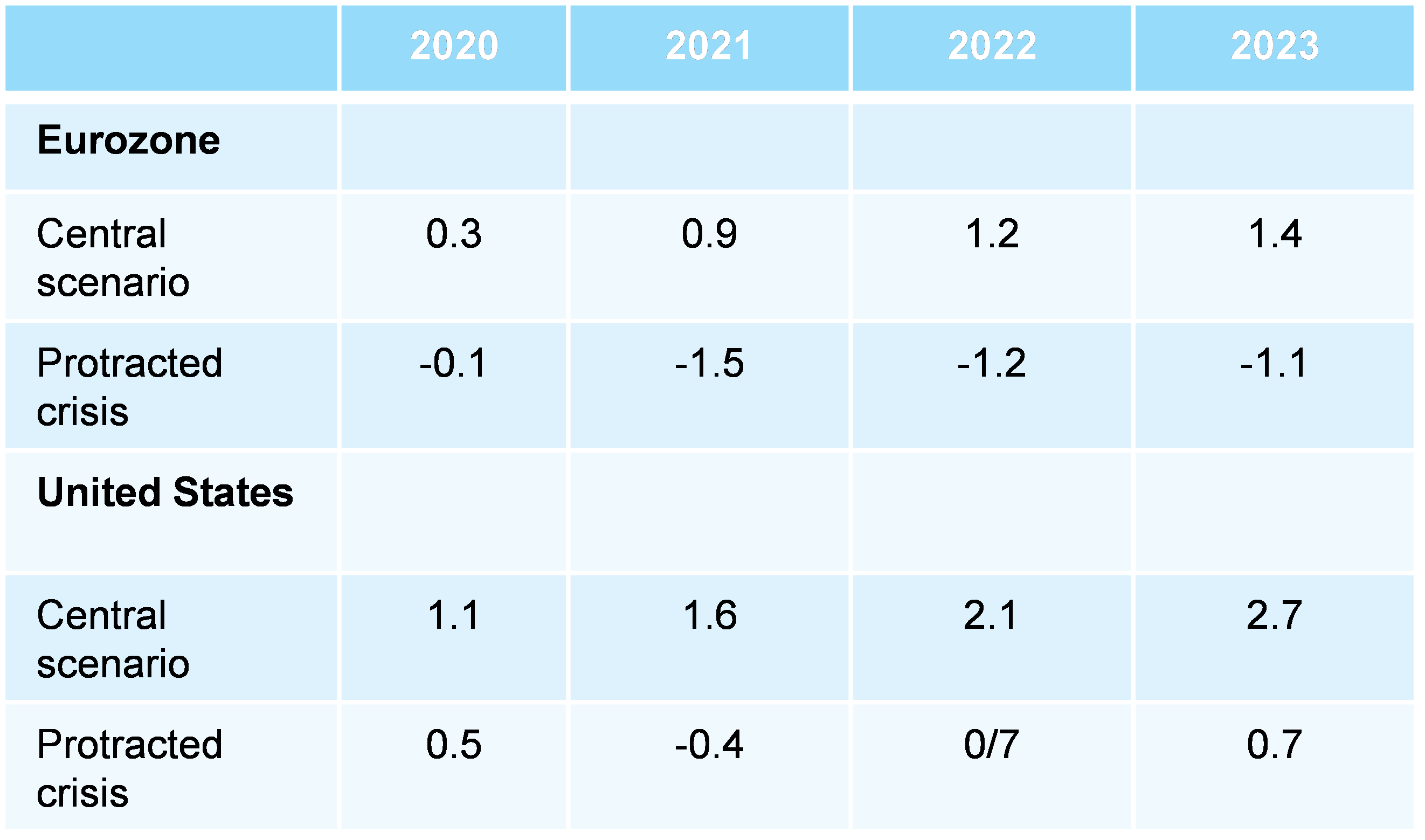

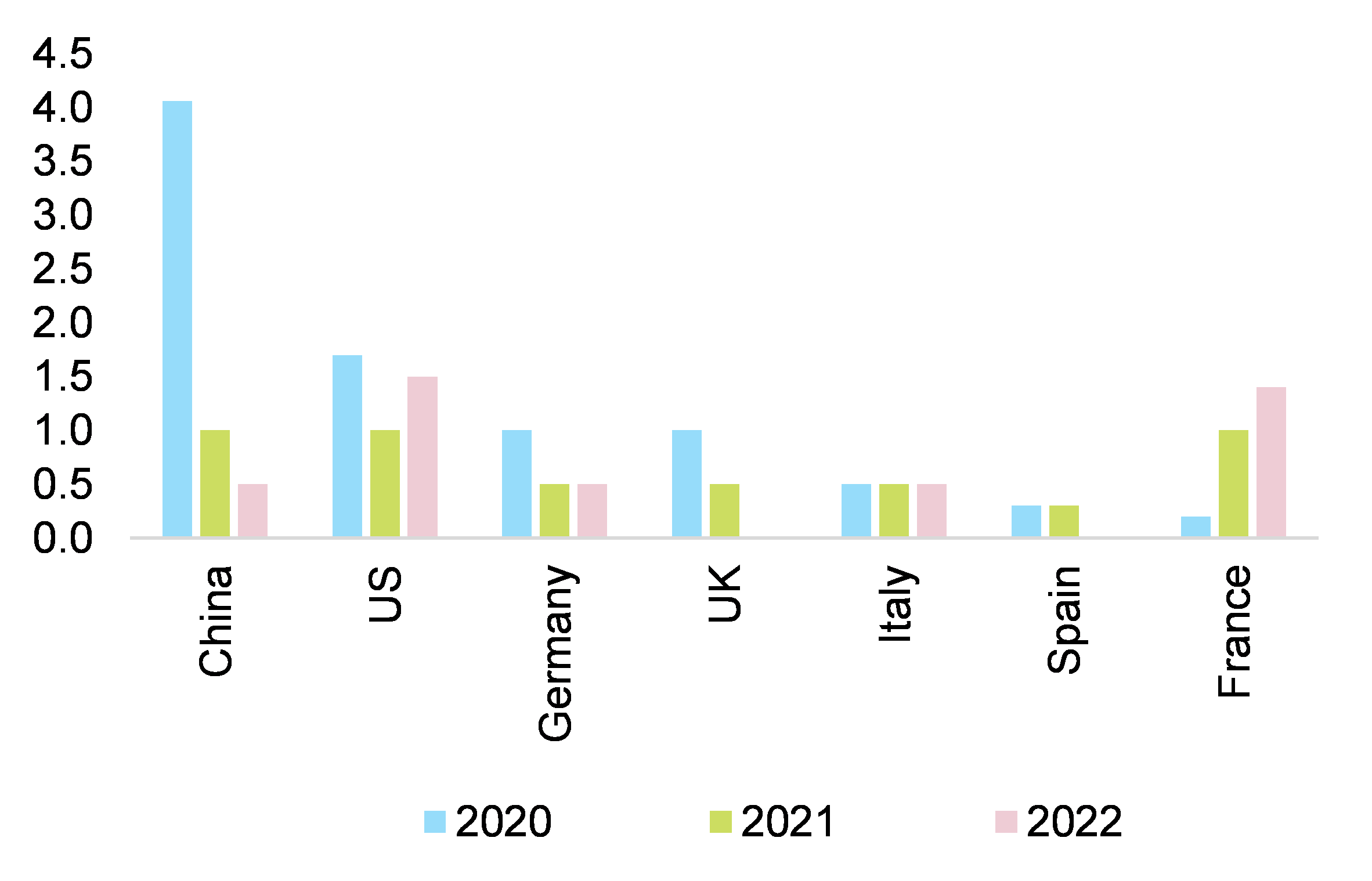

- Stop-and-go containment measures confirm a return to normal in 2022. After strong post-lockdown catch-up effects, we expect the recovery to slow in Q4 2020 and Q1 2021 as distancing measures tighten again and ongoing job shedding keeps spending and investment in check. Therefore we lower our GDP growth forecasts for 2021 to +4.6% (vs. +4.8% expected in June), following a contraction of -4.7% in 2020. Q2 data has already confirmed diverging recovery paths, with China and its Asian trade partners, Germany and Brazil outpacing the rest of Western Europe and the U.S. The sharpest trend reversals in activity should be visible starting in Q4 2020 in Europe (mainly Spain, France and the UK), the U.S. and in Emerging Markets such as Brazil and Mexico. In this context, the gradual phasing out of temporary policy measures designed to support companies will lead to a major trend reversal in business insolvencies, with a +31% increase expected by the end of 2021.

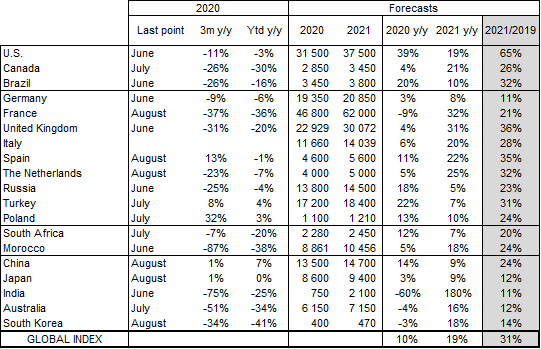

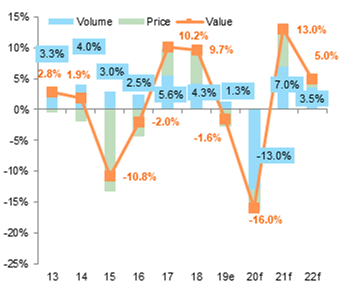

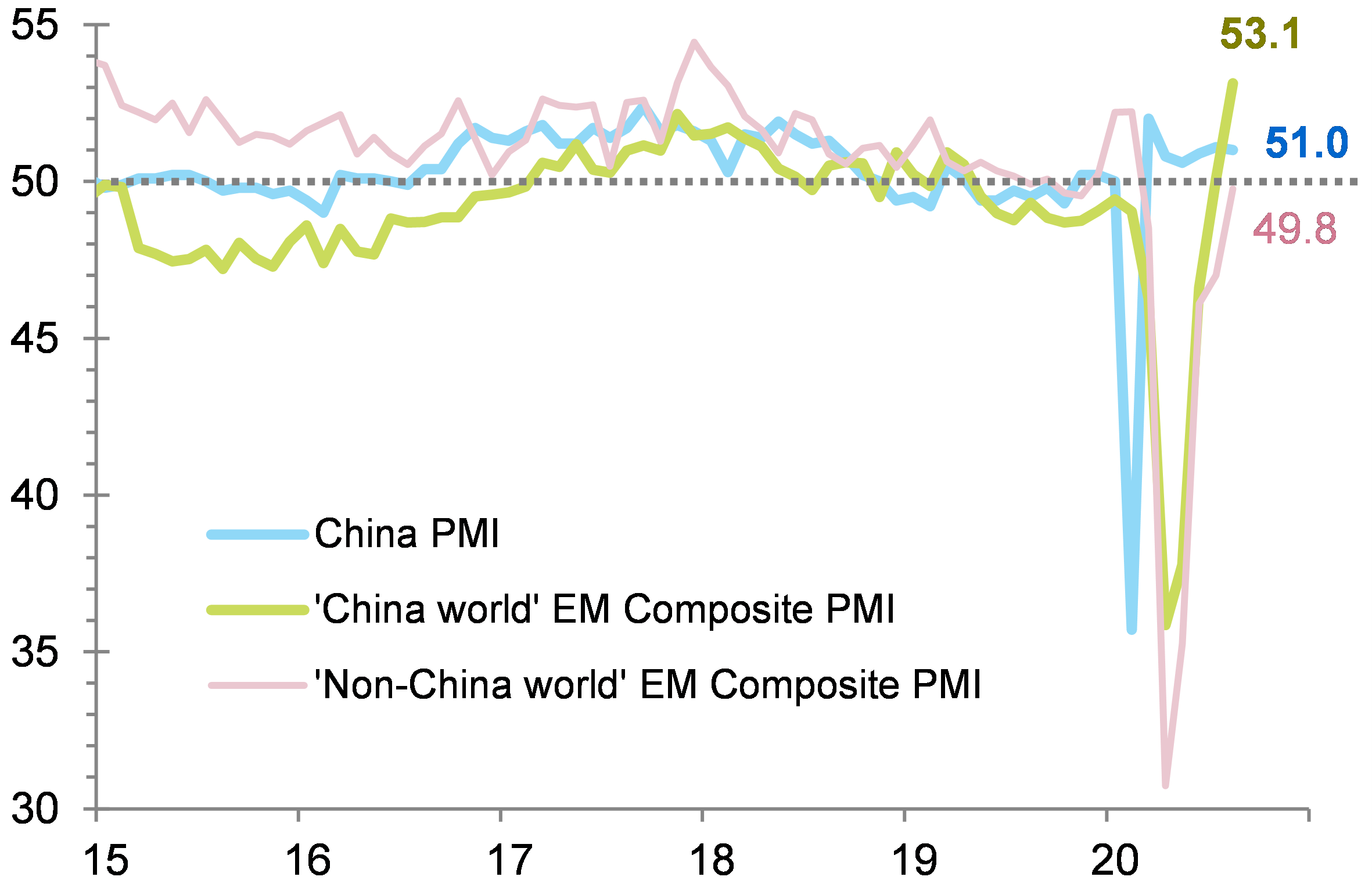

- A dual recovery for trade, consumers and investors. First, despite a stronger-than-expected recovery in goods trade worldwide, the U.S. and Western Europe are trailing China, Emerging Asia and Eastern Europe’s export recovery. In 2020, we forecast a fall in global trade in goods and services by -13% (vs.-11% in 2009) in volume terms, leading to USD4tn of trade losses. In 2021, we forecast a +7% technical rebound but expect a return to pre-crisis levels only in 2022 as services continue to struggle and calls for de-globalization emerge. Meanwhile, a loss of purchasing power for the most fragile households will be hard to recover. The asymmetric exposure to job losses meant young, less qualified and part-time workers were hit the hardest, implying a K-shaped or “dual” recovery in consumer spending ahead.

- Political risk could be back like a boomerang. Odds for a no-deal Brexit have risen to 45%, while the U.S. elections are paving the way for a new fiscal cliff and a judiciary dispute at the end of the year. In 2021, the tech war between the U.S. and China, tensions in the Mediterranean Sea and the U.S.-Russia dispute will remain top of mind. The risk of policy mistakes for Emerging Markets that loosened their fiscal discipline to fight the crisis will rise in 2022: anticipations of higher U.S. rates should materialize then and debt sustainability worries could trigger pressures on EM currencies.

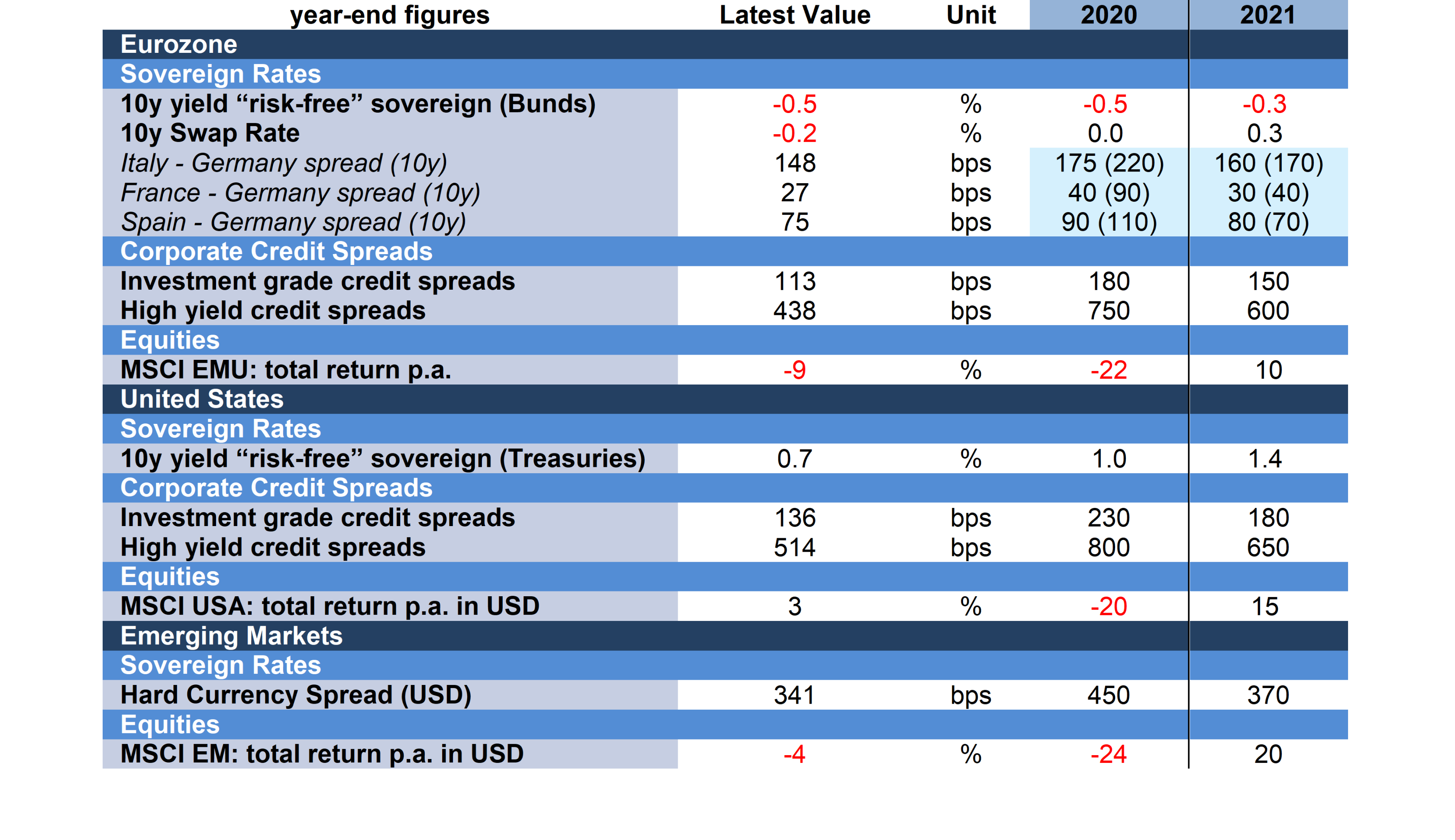

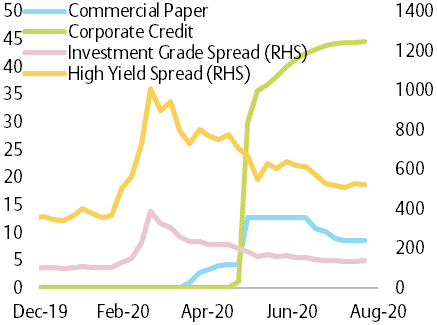

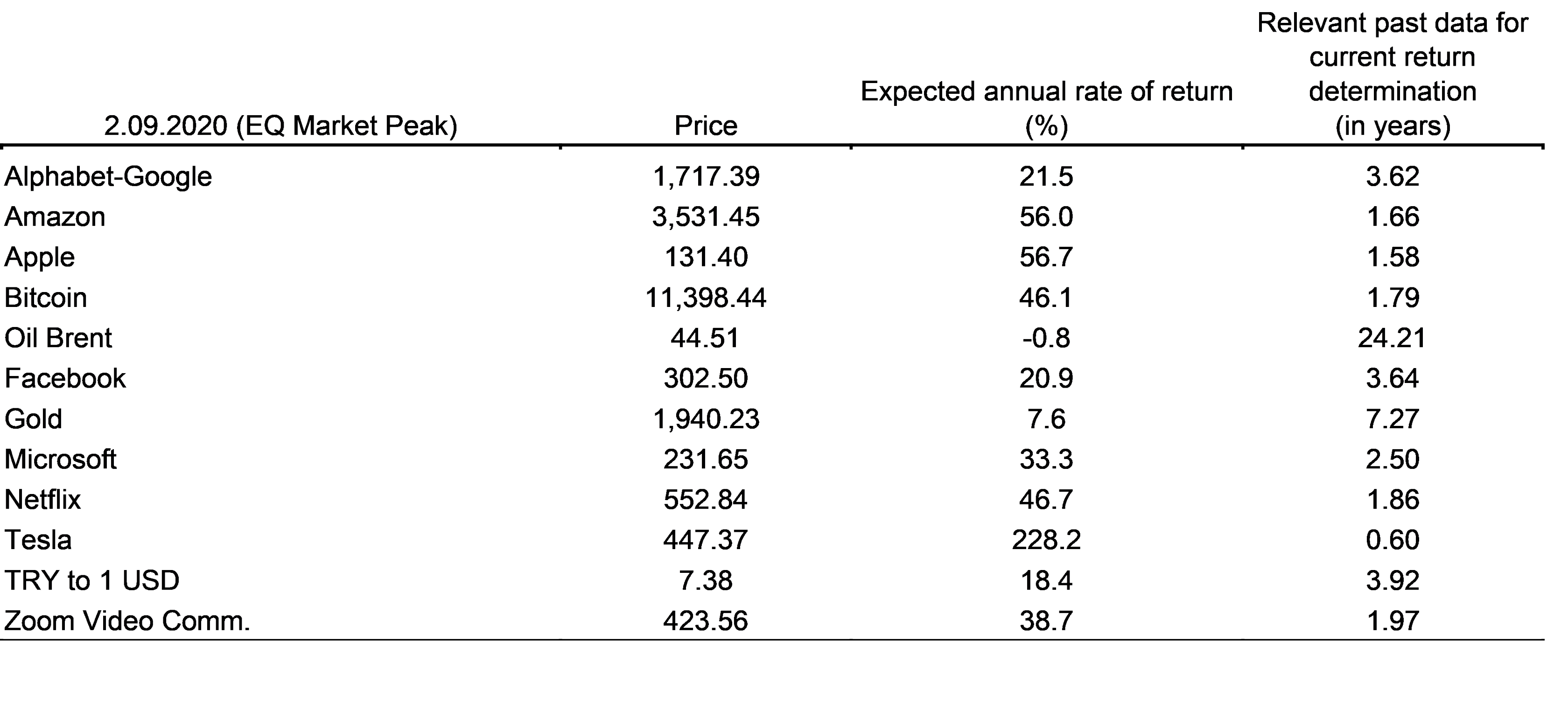

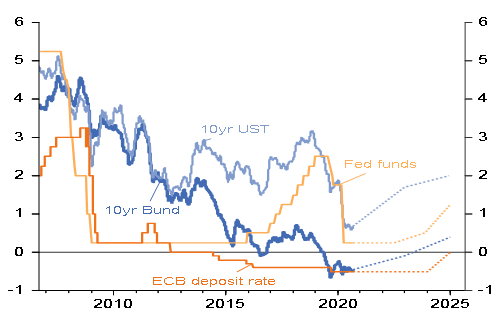

- Not the time to take risks. In the current market environment, it is important to consider that there is greater economic uncertainty now than at the beginning of the year, despite the current monetary and fiscal policy mix, as well as more geopolitical risks and tighter valuations. In this context, equity markets show a persistent detachment from fundamental determinants, making the recent rally hardly justifiable. Because of that we still expect the equity market to underperform in 2020 and to start a muted rally in 2021. When it comes to corporate credit, both investment grade and high-yield corporate spreads look too tight. As in equities, corporate credit markets remain detached from fundamentals on the back of the central banks’ perpetual put option. Hence, we expect corporate spreads to converge towards higher values due to higher than expected market volatility and increasing default rates. Lastly, with the short-end of most developed countries’ sovereign yield curves anchored by their respective central banks, we expect a timid curve steepening towards the end of 2020 and 2021. This gradual increase in term premium will occur on the back of higher inflation expectations and a halt in the recent decline of real yields. On the other hand, long-term Emerging Market sovereign spreads look overbought. The combination of this extreme bullish positioning and the current market fragility is a perfect combination for EM assets to become a victim of a second “risk-off” rotation in the wake of a second risky-assets market correction.

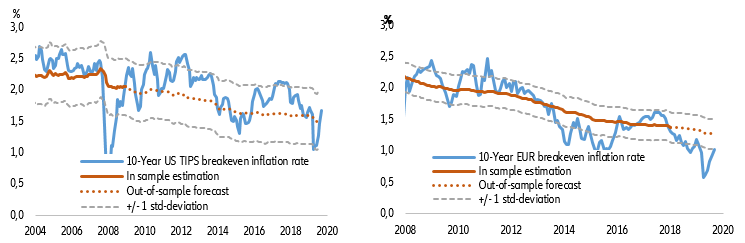

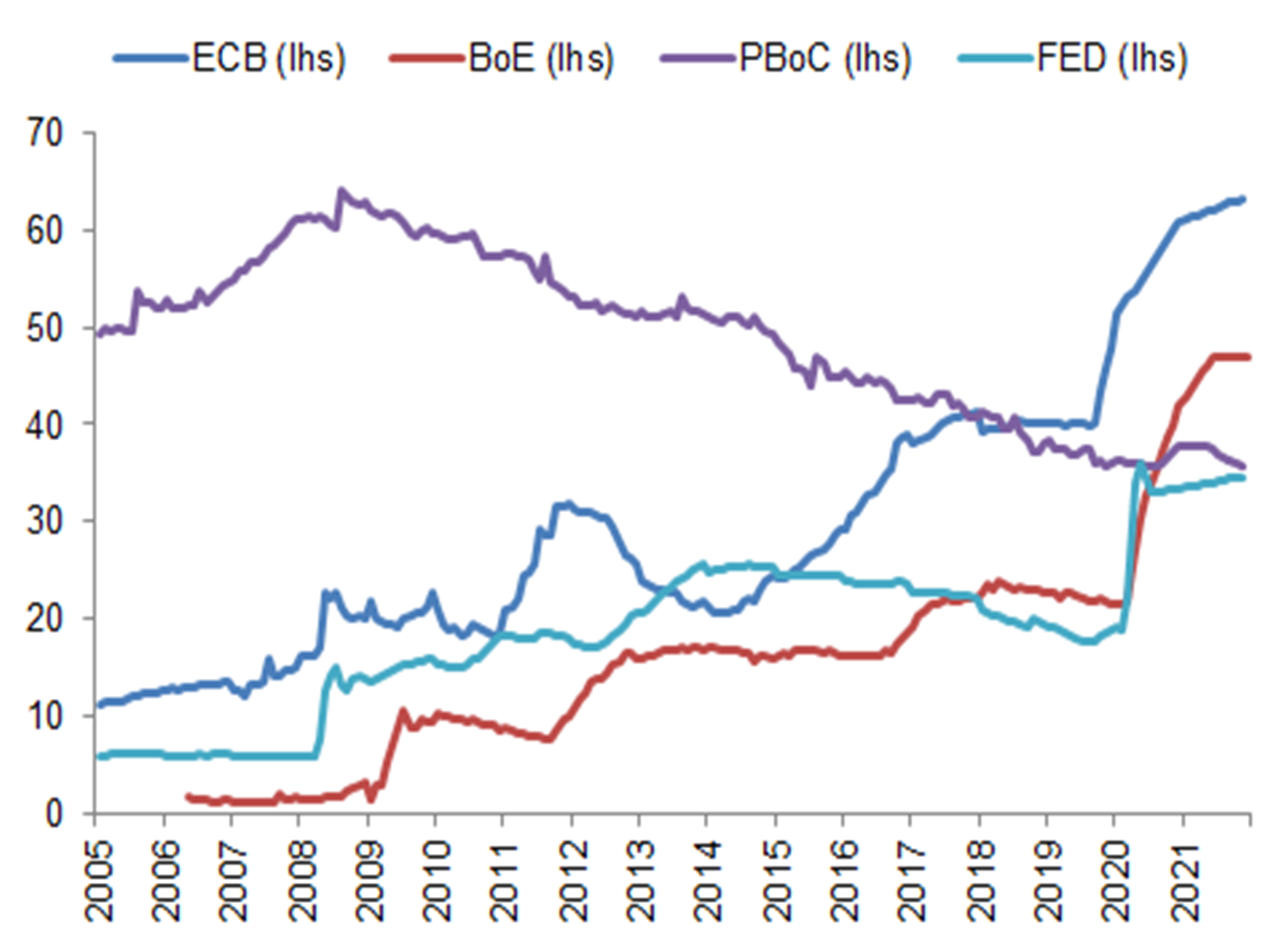

- Fiscal and monetary policy: The devil is in the details. EU member states agreed on issuing common debt to boost the recovery in a historical move. Yet the different natures and spending calendars of fiscal policies will matter: countries focusing on (short-term) demand (Germany, U.S., China etc.) could see a faster recovery than those betting on supply (France). Some countries still need to do more (Spain, Italy, the UK). In the immediate crisis aftermath, inflation is likely to remain muted despite these policy impulses; we see it moderately and temporarily overshooting in the US starting in 2022. On the monetary policy side, we expect an acceleration of the U.S. Fed’s securities purchases in H1 2021, with a tapering of its QE program to only start from mid-2022 and a first rate hike in Q3 2023. The ECB should announce an additional EUR500bn in Quantitative Easing in December 2020.

- Scarring effects? Covid-19 has changed the rules of the game for economic growth and capital markets. First, the fight for regional primacy will lead to a regular “weaponization” of technology, trade, currencies and payment systems. Second, the balance between the state and markets will change, to the disadvantage of the latter. And as the state gets more and more entangled in the private sector, market dynamics for innovation will get weaker while the number of zombie companies rises. Private players in social security – such as life insurers – might be pushed against the wall. The growing role of the state also has ramifications for monetary policy. High (unsustainable) debt levels will force central banks to backstop sovereign and corporate bond markets to ensure favorable refinancing conditions. In the end, these ultra-expansionary monetary policies may strip markets of their ability to price and allocate resources appropriately and encourage excessive risk-taking by both debtors and investors. However, every cloud has a silver lining: Covid-19 has showed how quickly change is possible; it is a welcome break-up of encrusted structures and a boost to digitalization. The way we work has changed for good. Future work will see more remote working and flexible team structures but less business trips. Finally, it has also raised society’s risk awareness, including for low-probability, high impact tail risks. The upshot: More demand for and better pricing of risk cover. This should be a boon for insurers – if they are able to offer comprehensive and simple solutions.

A stop-and-go approach until the return to normal in 2022

Q2 data confirmed an unprecedented contraction in global GDP (-6.1% q/q vs. -7.0% q/q expected by us) after the Covid-19 shock, close to four times worse than the 2009 trough and double the Q1 contraction. However, some countries were hit much harder than others due to differences in lockdown intensity and in the structure of their economies (share of services vs. manufacturing): France (81% of pre-crisis GDP level), Italy (83%), the UK (78%) and Spain (77%) were much more impacted than the U.S. (90%), Germany (88%) and the Netherlands (90%).

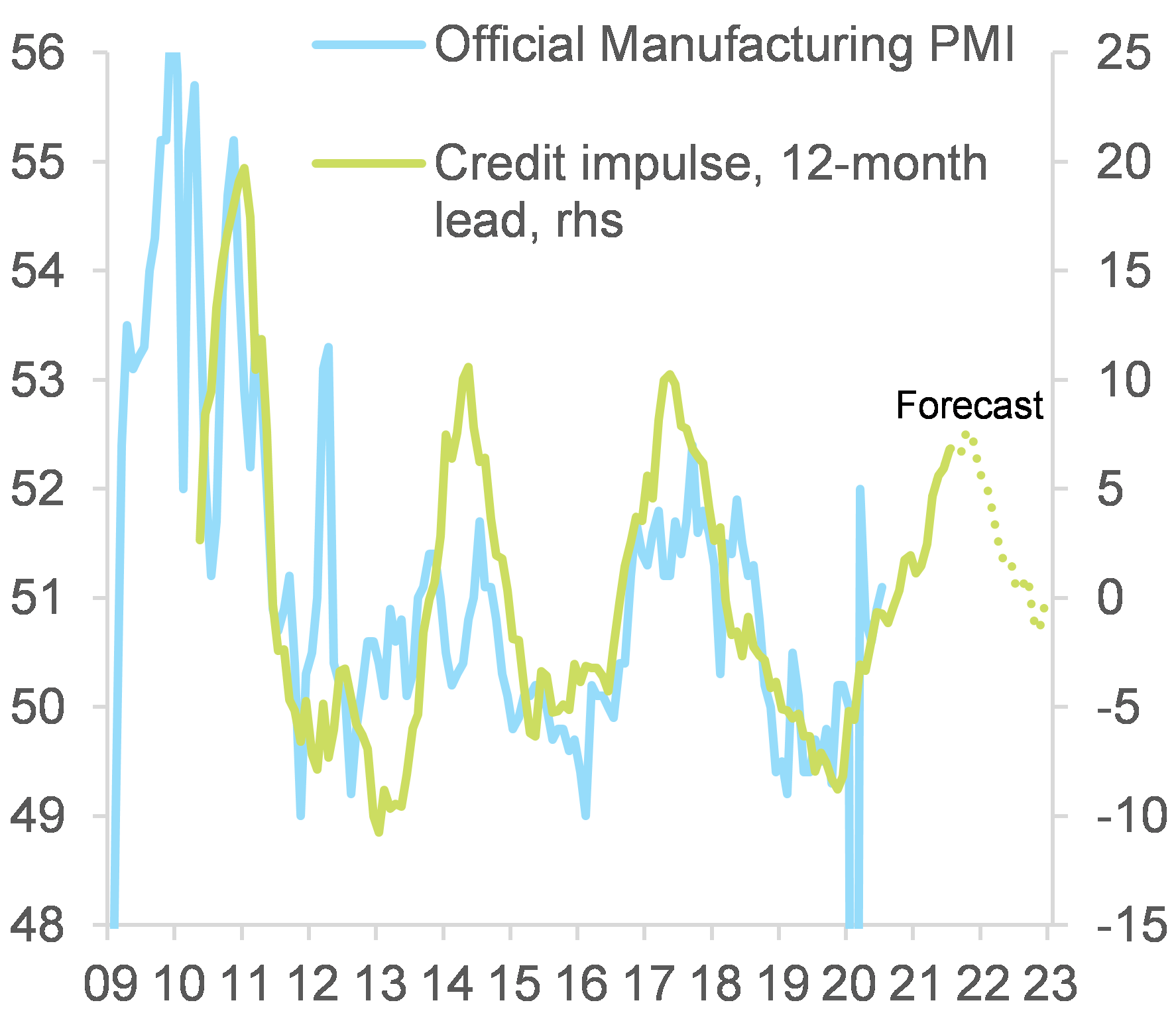

During the summer, de-confinement strategies gained traction, allowing several positive surprises in the economic data, notably for order books, the residential market and retail sales, thanks to pent-up demand post-lockdown. On the industrial side, global production stood at -8% y/y in June (after a trough at -16% y/y in April) and confidence in the manufacturing sector reached pre-crisis levels. This confirmed our call of a faster return to pre-crisis levels for activity in the manufacturing sector (vs. services).

However, we think the recovery will lose steam in Q4 on the back of tighter sanitary restrictions and the ongoing job shedding, which will keep spending and investment plants in check.

We remain in Phase 2 of the Covid-19 crisis, which means re-opening will remain divergent and dependent on the evolution of the sanitary crisis. Back in April we identified four different phases of the Covid-19 crisis. During phase 1, characterized by the urgency of monetary, fiscal and sanitary measures, real activity suffered heavily from the lockdowns, as mirrored by the sharp contraction of GDP across countries. Now, we are in phase 2, characterized by more targeted and progressive sanitary restrictions in response to rising infections, with persisting threats of a lockdown in countries where the second wave materializes. Hence, the recovery is expected to soften in Q4 and in some cases transform into a W-shaped one. We expect the highest trend reversal activity in Q4 in Europe (France, Spain, UK) and in the U.S.

Phase 3 of the Covid-19 crisis: Transitioning towards normalization, with a stop-and-go approach until the end of 2021. During phase 3 (from Q4 2020 until end-2021), we expect a succession of tighter and targeted sanitary restrictions, followed by periods of easing. This stop-and-go trend in stringency will continue until end 2021, assuming a vaccine would be widely available from September 2021 and that at least 6 months would be needed for vaccination campaigns. While it will not freeze the new investment cycle, it will hamper it, causing asymmetries across countries due to heterogeneous initial conditions, different sized stimuli, variable re-confinement strategies and unequal potential access to potential vaccines. Phase 3 will also see the implementation of new fiscal stimulus packages but a slightly lower degree of central bank activity, keeping the global economy below pre-crisis levels until end-2021.

Still some way to go until we reach the fourth and final phase of the Covid-19 crisis: What would it take for a full normalization by 2022? We assume a finalization of vaccination campaigns in mid-2022. From the beginning of 2022 onwards, vaccines should be available at a large scale for the most advanced countries in this race (Russia, China, UK and the U.S.) and be progressively distributed to the rest of the world. In line with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) own assessment, the full distribution of a vaccine at a global level could be completed by the end of 2022. In this context, stringency indices should return to their minimum levels and 80% of global GDP will be back to pre-crisis levels. However, we should not underestimate the risk of a possible temporary disruption in the transportation sector during the global vaccination campaign. In fact, vaccine delivery could mobilize half of the global transportation capacity for several months.

Figure 1 – Real GDP forecasts, %