At its meeting on 16 September, the last before the election, the U.S. Federal Reserve confirmed our expectations that it will keep rates at 0% into 2023, and let inflation run higher than 2% for an extended period. It was the first meeting since Chairman Jerome Powell’s Jackson Hole speech in which he announced the policy shift to average inflation targeting (AIT) that effectively focusses on pushing inflation up to 2% for an extended period. In particular, the Fed’s statement read “The Committee seeks to achieve maximum employment and inflation at the rate of 2 percent over the longer run. With inflation running persistently below this longer-run goal, the Committee will aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time so that inflation averages 2 percent over time and longer-term inflation expectations remain well anchored at 2 percent. The Committee expects to maintain an accommodative stance of monetary policy until these outcomes are achieved. The Committee decided to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and expects it will be appropriate to maintain this target range until labor market conditions have reached levels consistent with the Committee's assessments of maximum employment and inflation has risen to 2 percent and is on track to moderately exceed 2 percent for some time.”

In fact, the “dot-plot” accompanying the announcement shows that 16 out of 17 Fed members expect rates to stay near 0% through 2022, and that 13 out of 17 members still expect rates to stay near 0% through 2023. The statement also signaled that the Fed is willing to let the labor market run hotter than it would have before. The Fed also made another move towards more accommodative monetary policy, saying that its bond-buying program, which originally was meant to promote the smooth functioning of credit markets, would now also be used to help boost the economy. The new wording read that the bond-buying would “…help foster accommodative financial conditions, thereby supporting the flow of credit to households and businesses.” In the press conference following the announcement Powell said, “My sense is that more fiscal support is likely to be needed. Of course, the details of that are for Congress, not for the Fed. But I would just say there are roughly 11 million people still out of work due to the pandemic and good part of those people were working in industries that are likely to struggle. Those people may need additional support as they try to find their way through what will be a difficult time for them…” Finally, the Fed upgraded its previously overly pessimistic outlook, increasing its forecast for 2020 GDP to -3.7% from -6.5% and lowering its 2020 unemployment projection to 5.5% from 6.5%. Projections for 2021 were also modestly revised in a stronger direction.

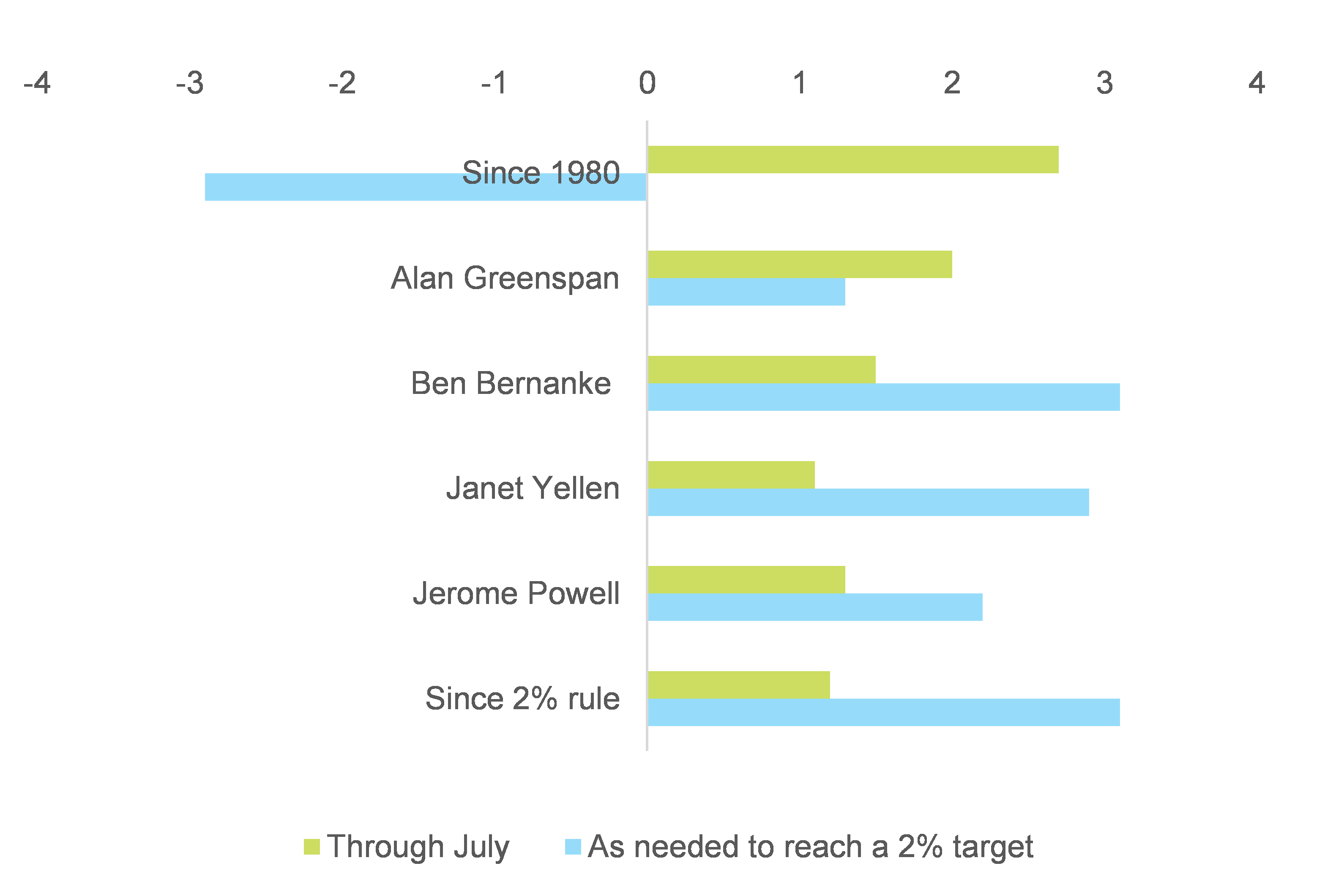

Besides indicating the urgency of supporting growth amid the Covid-19 crisis, the AIT move is a confession of the U.S. central bank's powerlessness in hitting the inflation target over the medium-term. Over the last 20 years, all the FOMC Chairs have constantly failed in hitting the 2% target officially adopted in 2012.

Figure 1: Average inflation performance (through July 2020) of the Fed’s different leaders (%)