Executive summary

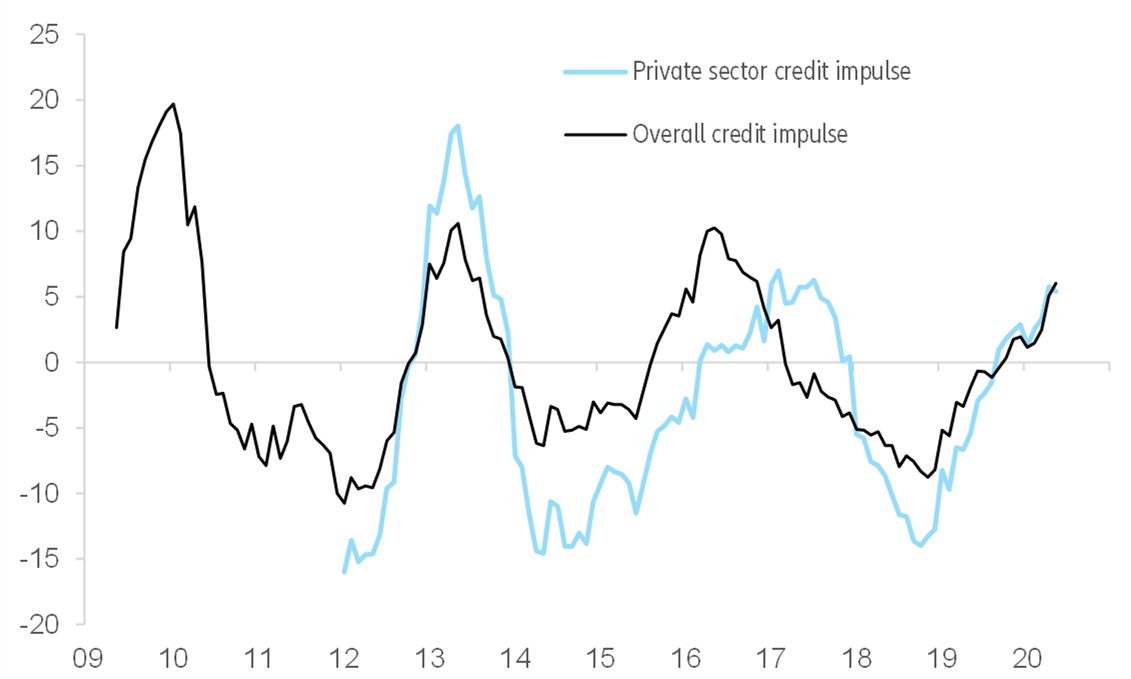

- In China, financial and monetary conditions are clearly easing, as measured by our credit impulse index: as of May 2020, it stood at 6.0pp, up from 1.9pp at the end of 2019. However, the PBOC’s stance appears to be much more prudent compared to other major economies. Monetary stimulus in China currently is one third of that in 2009-10. According to our forecasts, more than 3/4 of monetary easing for this year has already been implemented. As the economic recovery is on track, the PBOC is likely shifting from a proactive to a wait-and-see stance.

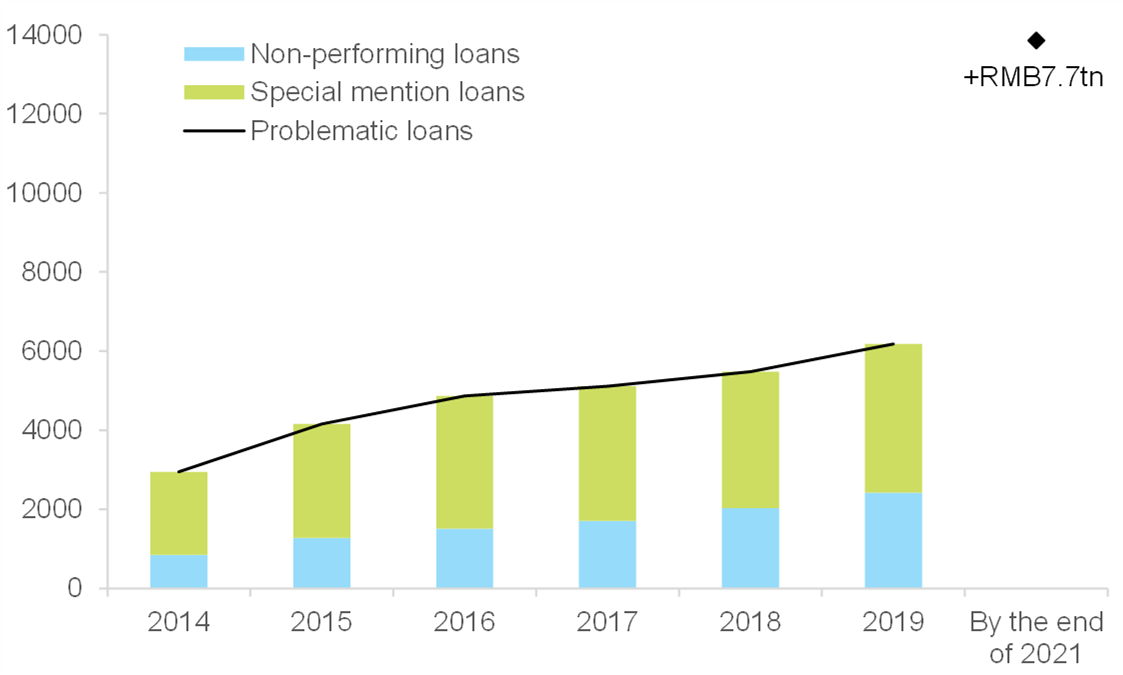

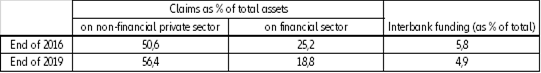

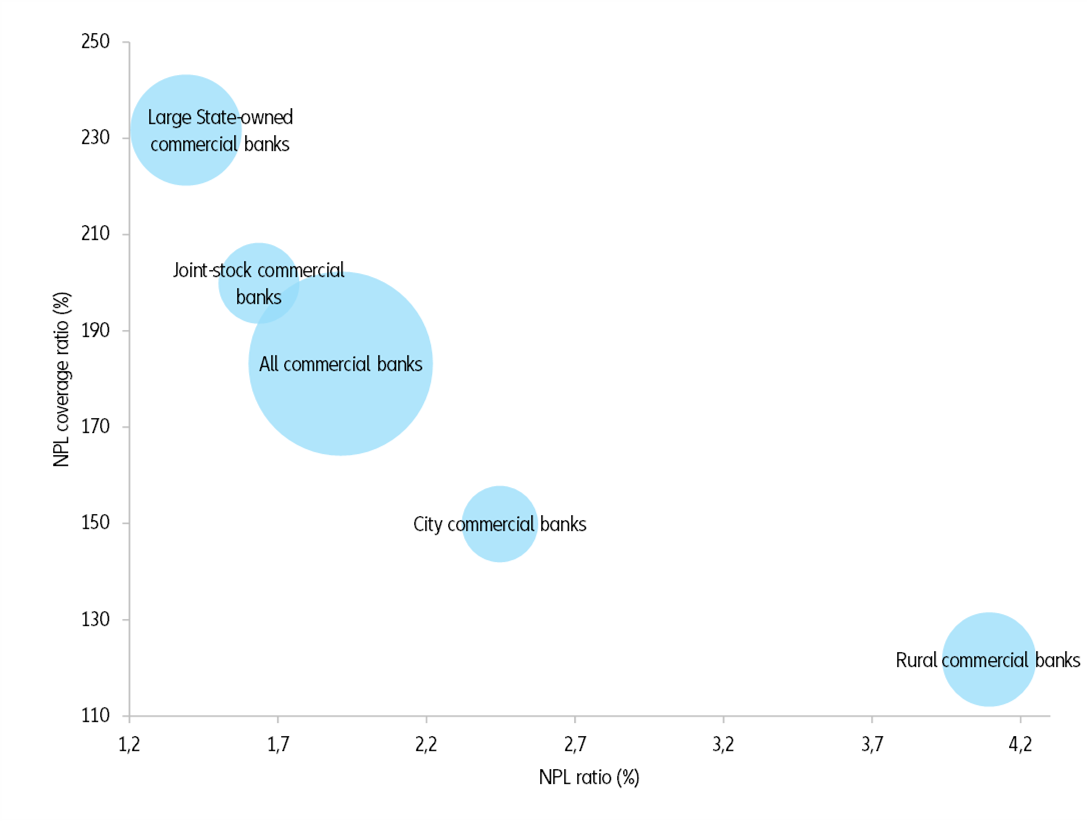

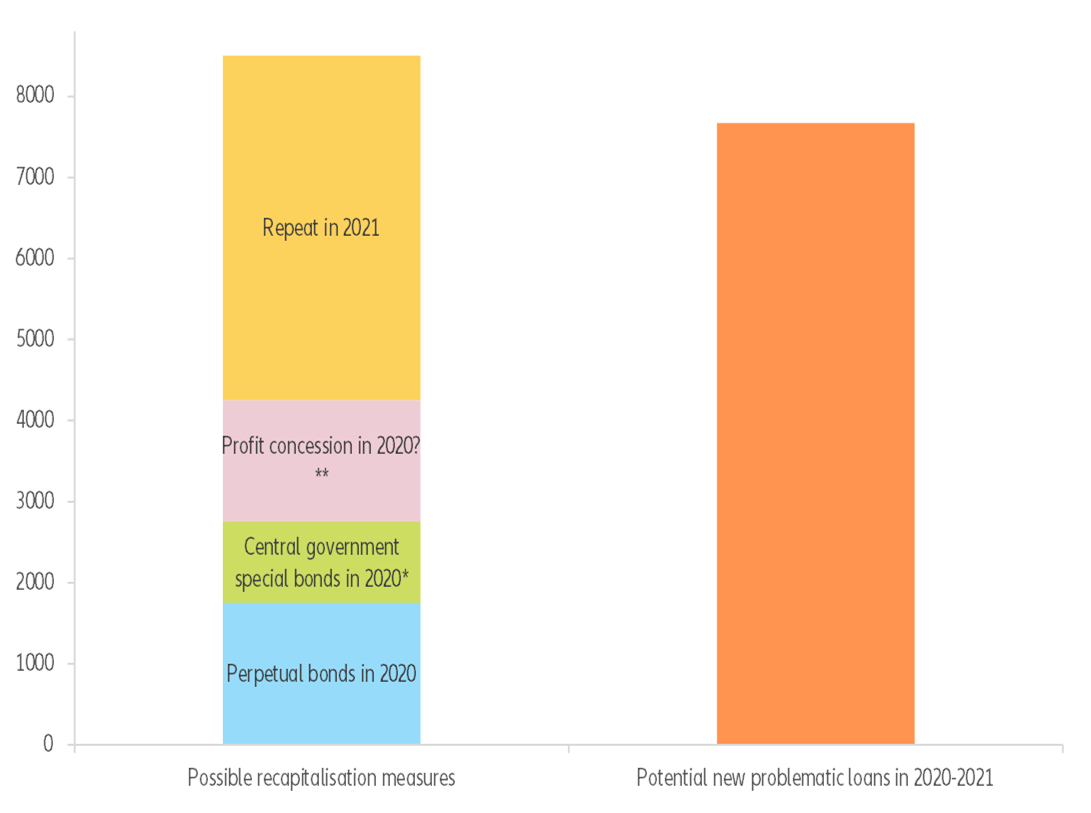

- The ongoing credit easing amid the Covid-19 shock will worsen banks’ asset quality. We estimate that by the end of 2021, ‘problematic’ loans could increase by +124% (+RMB7.7tn) compared to the end of 2019. We find that recapitalization tools available to banks (e.g. perpetual bonds, central government special bonds, profit concession) are enough to cover potential losses incurred by these problematic loans. The financial de-risking campaign launched in 2017 managed to improve China’s overall bank asset quality and reduce systemic risk, making a systemic event unlikely in the short term. That being said, individual non-systemic failures among smaller city-level and rural banks, like in 2019, are still likely.

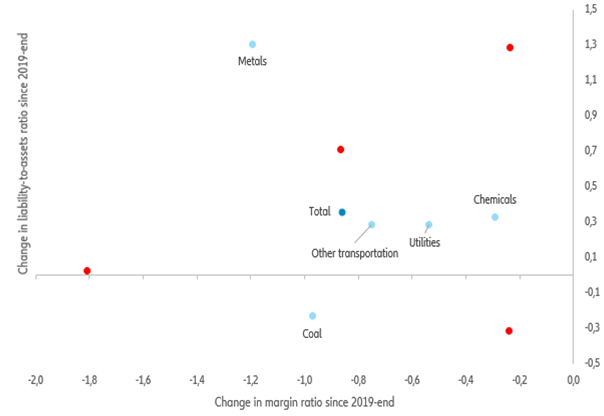

- What does this mean for companies? While we expect GDP to come back to its pre-crisis level in early 2021, and GDP growth at +7.6% for the full year, we forecast insolvencies to increase by +40% over 2020-21 v. 2019. Deteriorating credit quality will significantly push the number of zombie companies higher, mainly in the automobile, textile and agrifood sectors. These sectors have seen declining profitability and rising indebtedness since 2015.

Monetary stimulus is one third of that in 2009-10

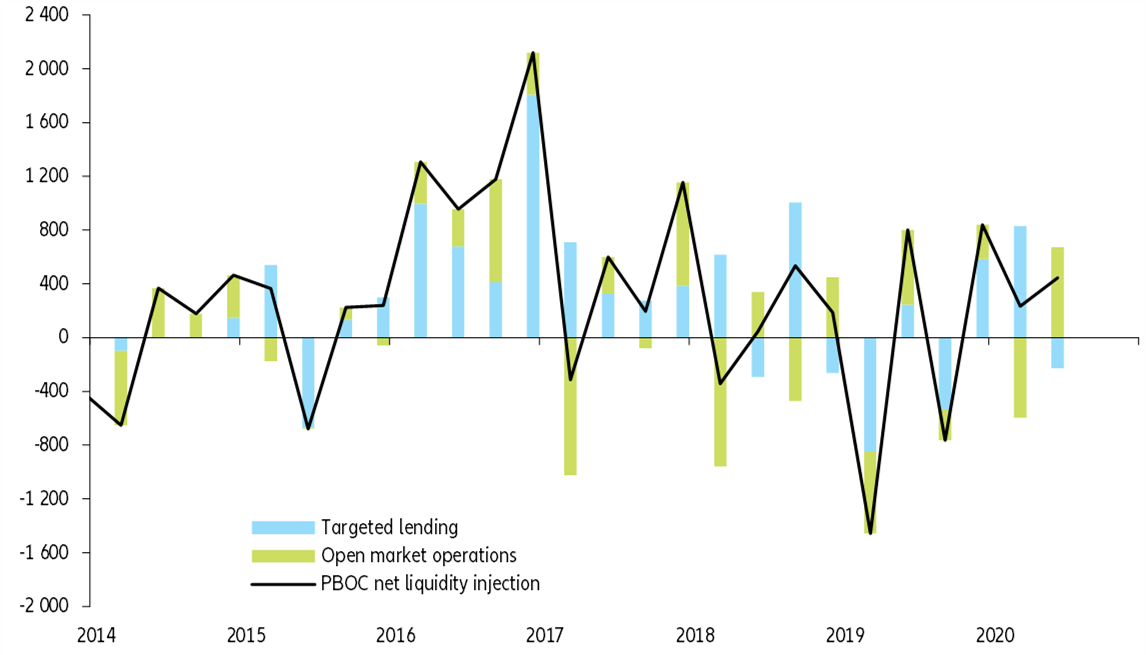

The Covid-19 pandemic and its related lockdowns have resulted in an unprecedented shock to the global economy. Central banks across the world have been quick to react, increasing funding and injecting liquidity. While the global response has been synchronised (differing from previous crisis reactions in recent history), the intensities differ. In China, financial and monetary conditions are clearly easing, but the central bank’s stance appears to be much more prudent compared to other major economies. More precisely, we expect the balance sheet of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) to expand by +5% of GDP in 2020, compared with +14% for the U.S. Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank.

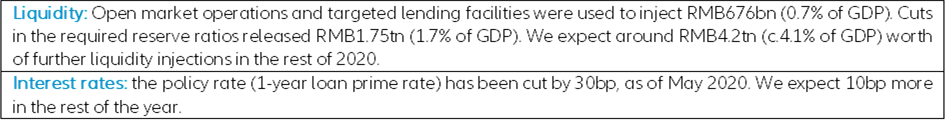

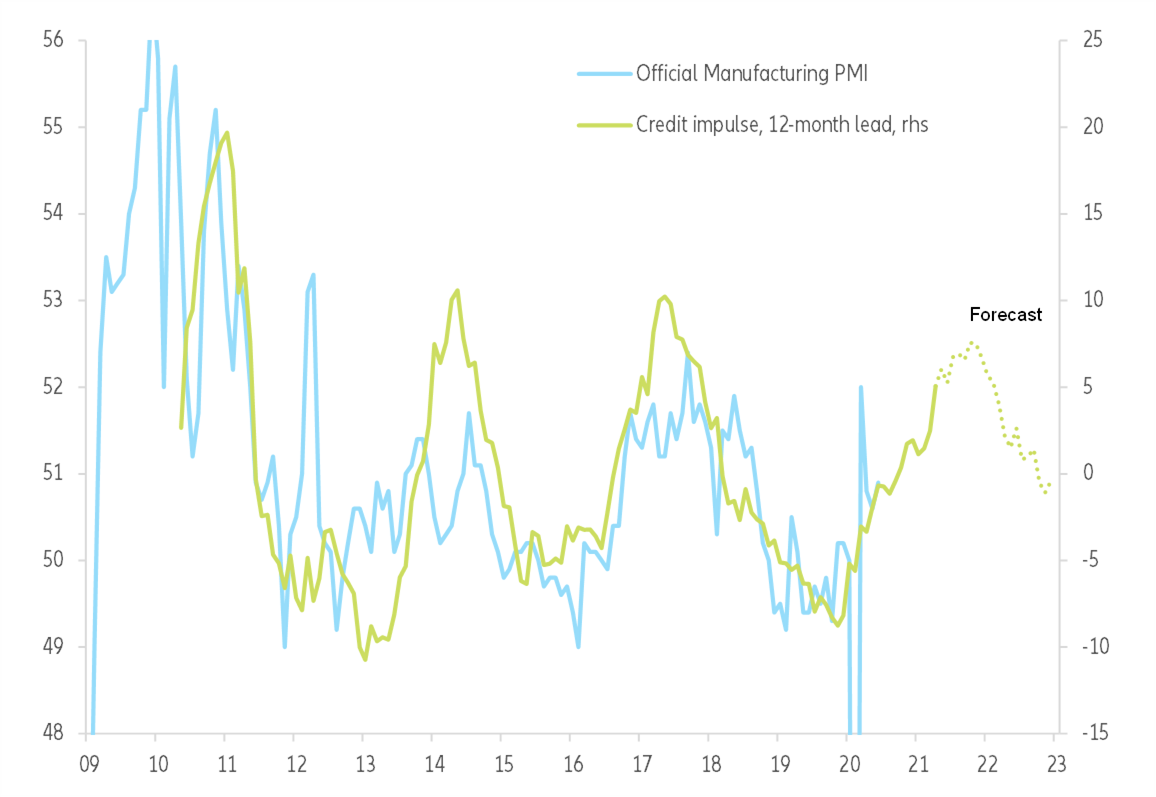

In the U.S. and the Eurozone, the yearly expansion of central banks’ balance sheets is the fastest observed in recent history. The situation is different in China. We have built a proprietary credit impulse index to better gauge the efficiency of monetary policy, and compare it with previous rounds of stimuli. This index is defined as the change in new credit issued as a share of nominal GDP. For credit data, we use the monthly aggregate financing data published by the PBOC (in particular bank loans, shadow-bank financing, bonds and stocks) and government bonds data. Our credit impulse index has a predictive power on cyclical economic indicators, exhibiting in particular a 12-month lead on the official manufacturing PMI.

The PBOC used the many tools at its disposal to ease the monetary policy (see Table 1). As of May 2020, our credit impulse index stood at 6.0pp, up from 1.9pp at the end of 2019 (see Figure 1). This improvement was driven by an acceleration in bank loans, stocks and corporate and public bonds issuance. After two years of decline, driven by regulatory tightening, shadow-bank financing is now rising again, but at a slow pace.

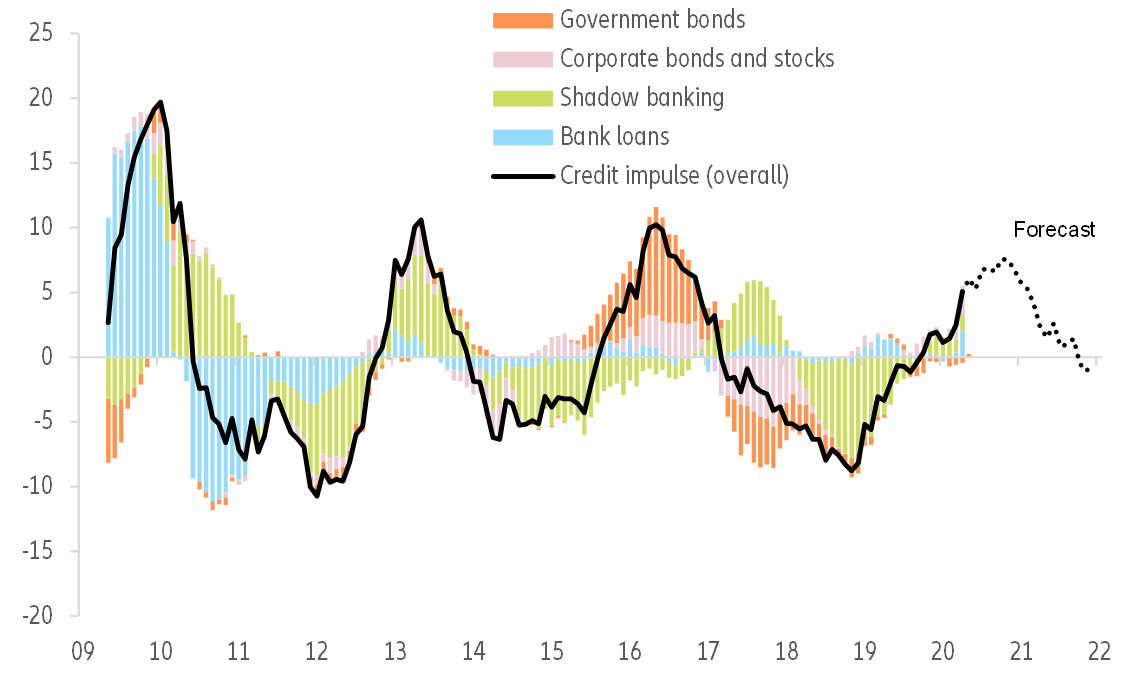

Table 1: Main monetary policy measures in 2020