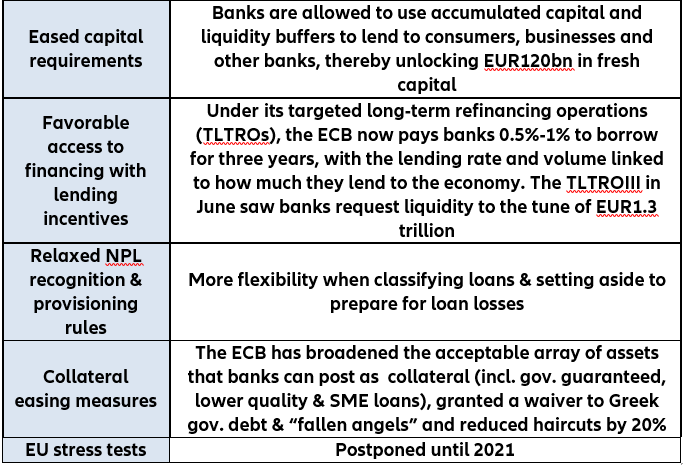

Figure 1: Covid-19 banking sector support measures

Figure 1: Covid-19 banking sector support measures

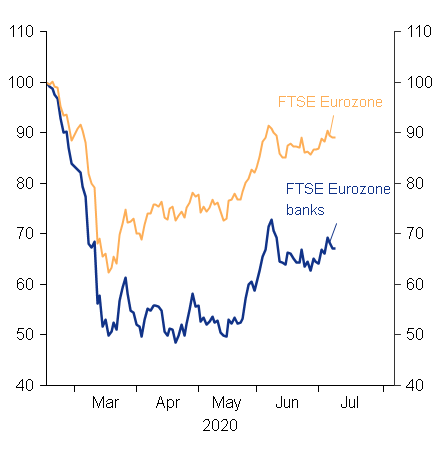

Who’s afraid of credit risk? Unprecedented policy support may not be enough to shield European banks from the real economy’s woes. The day will come when the banking sector will have to face the reality i.e. that amid the sharp economic downturn and the expected gradual recovery, non-performing loans are bound to increase notably. The market valuations of hard-hit banks amid the Covid-19 outbreak, which have only participated in the financial market recovery to a limited extent, provide a glimpse of the sector’s exposure to second-round effects.

Figure 2: FTSE Eurozone vs. FTSE Eurozone banks, Index: February 17=100)

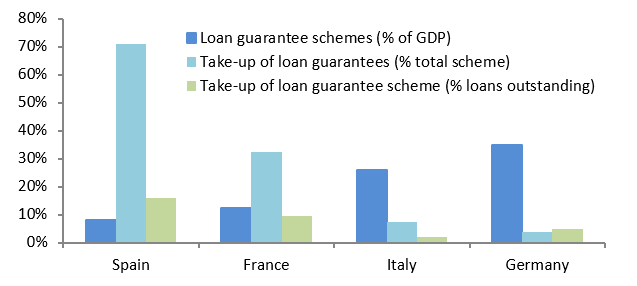

Figure 3: Public loan guarantee schemes in perspective

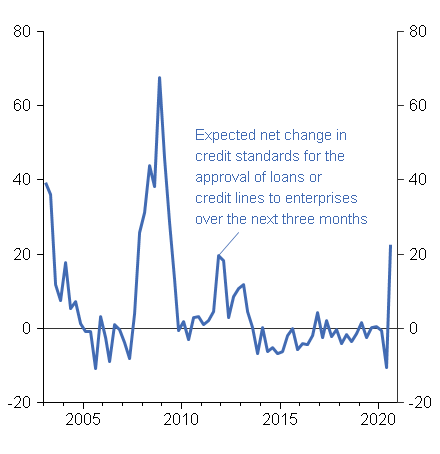

Expected credit tightening in the second half of 2020 highlights emerging risk of a credit crunch. Banks’ expectation of “a considerable net tightening of credit standards on loans to enterprises” as soon as the third quarter of 2020, as expressed in the Q2 ECB’s bank lending survey, should serve as a warning shot to policy makers to not pull the plug on support measures too early.

Figure 4: ECB bank lending survey – Expected net change in credit standards for the approval of loans to enterprises over the next three months

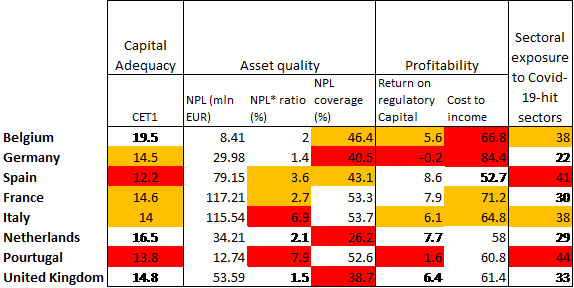

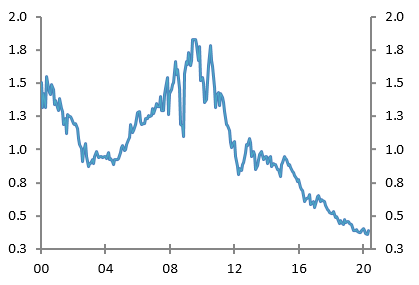

Most banking sectors were already fragile before taking a hit from the Covid-19, the result of excessive risk-taking in a decade-long historically low interest rate environment. Our stock-taking exercise reveals various pockets of vulnerabilities (in terms of capitalisation, asset quality, profitability and sectoral exposure) that have emerged over the past few years in the Eurozone banking sectors:

Capital Adequacy: Spain, Italy and Portugal fair less well although the aggregated capitalization levels of their sectors remain above the regulatory thresholds (slightly below 12%).

Asset quality: France and Italy boast the largest total amounts of NPLs in Europe, though this is partly explained by the size effect for France. Turning to the NPL ratio, it is higher than the European Banking Authority, indicative benchmark of 5% in Italy and Portugal. Regarding the provisioning of NPLs, the Netherlands and the UK happen to have the weakest coverage of NPLs, which exposes their banking systems to a sudden deterioration of asset quality.

Profitability: Germany is by far the worst performer in terms of profitability and cost efficiency, despite the long-lasting consolidation efforts of the sector. Return on equity is also weak in Portugal, while Belgium stands out with weak cost-efficiency. As low interest rates are becoming the ‘new normal’, these countries could face rising pressure to adapt their business models to remain profitable.

Exposure to Covid-19 hit sectors: Banks in Portugal and Spain have the largest credit exposure to those sectors that we expect to be hit the hardest by Covid-19, including transportation & storage, accommodation & food service, art, entertainment & recreation, retail & wholesale, industry and construction . In the final quarter of 2019, these sectors already boasted large NLP ratios at the EU level: construction reported the highest NPL ratio (15%) while accommodation & food services as well as arts, entertainment & recreation also had elevated NPL ratios (9% and 8%, respectively).

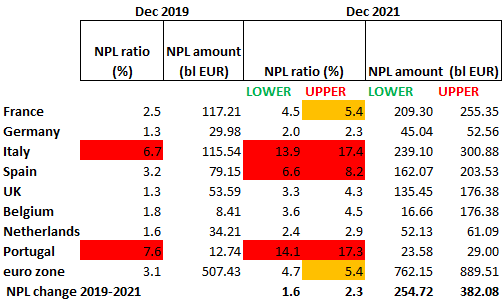

Figure 5: Banking sector soundness indicators (as of December 2019)

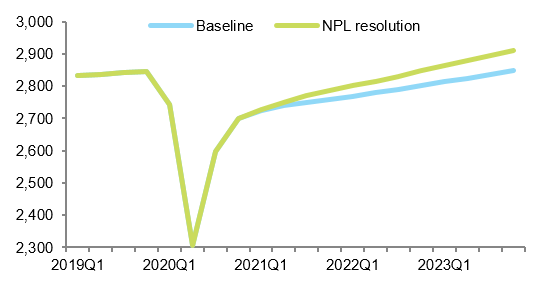

The deterioration of asset quality after Covid-19 is likely to impede banks’ willingness and ability to lend to the economy, which in turn risks delaying the start of the new investment cycle in 2021. Watch out for the usual suspects, including Italy, Portugal and Spain – particularly on asset quality – but also for Germany and Belgium on profitability. The Covid-19 crisis will worsen the above-mentioned vulnerabilities, in particular due to the deteriorating quality of loan portfolios in the hardest-hit sectors. According to our estimates, the Eurozone NPL ratio could rise back to post-GFC peaks – albeit staying below levels last seen during the 2012- 2013 Sovereign Debt Crisis. Based on our macroeconomic scenario and using the EBA stress test elasticities, we expect the Eurozone NPL ratio to increase from 3.1% in Q4 2019 to 4.7%-5.4% by end 2021. This would put between EUR255-380bn of additional NPLs (2.1-3.2% of 2019 Eurozone GDP) on Eurozone banks’ balance sheets by end 2021. Put differently, the resulting increase in sour loans would offset three years of progress made in reducing the Eurozone NPL ratio from 5.1% in end 2016 to 3.1% in end 2019. The deterioration in asset quality amid rising insolvencies would surely push banks to tighten credit conditions in 2021 in Italy, Portugal and Spain, but also in France. Further, deteriorating loan quality is likely to put bank profitability under pressure in Germany, Belgium and Portugal.

Figure 6: NPL loss simulations (2019-2021)

What is needed to avoid banking sector trouble? A European bad bank is certainly not for tomorrow, unless the protracted crisis scenario materializes, with the Eurozone NPL ratio rising to around 20%, so that national governments will remain firmly on the hook for now. What will policymakers be ready to do to support the banking sector in dealing with sour loans, after actively encouraging risk-taking? Public loan guarantee schemes are likely to be extended to 2021 in most Eurozone countries; meanwhile the ECB is likely to boost its support to the banking sector as soon as its September meeting by raising the tiering multiple (to shield more of banks’ liquidity), further sweetening the terms on TLTRO loans and/or including “fallen angels”, bonds that have lost their investment grade status, in its asset purchase programs.

But what structural remedies could be applied? Reports that the ECB is looking into setting up a European bad bank have fueled hopes that Europe has learned its lessons from the Eurozone debt crisis and is getting ready to tackle looming banking sector woes proactively. Under the circulating proposals, a TARP-style bad debt fund would issue bonds that commercial banks would buy in exchange for NPL portfolios. These bonds in turn would be eligible to be posted as collateral with the ECB to attain more funding.

However, don’t hold your breath for a European bad bank: Even though we deem it the most optimal response to quickly clean the European banking sector of NPLs, and in turn tackle the risk of a credit crunch, progress is unlikely to be swift:

- For one, the debate will probably fail to advance as it is deemed premature by policymakers as long as the extent of the Covid-19 related outfall for the banking sector remains highly uncertain.

- Moreover, the ECB could not do it alone, but would need other institutions such as the European Stability Mechanism to enter the scene to act as guarantors. While the ESM is already able to recapitalize banks, the right to purchase NPLs would probably require a treaty change. Expect a resumption of the risk-sharing vs. risk-reduction debate, compared to which negotiations around the EUR750bn Next Generation EU recovery fund – which is limited in size and duration – should look like a walk in the park.

- Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, the likely heterogeneous impact of Covid-19 on national banking sectors implies that shoring up the necessary political support will be a challenge. After all, our calculations suggest that NPL ratios in the big five Eurozone countries will remain in single-digit territory (with the exception of Italy), suggesting that the problem will remain one for national balance sheets and bad banks to digest. The downside here of course is that pressure on already fragile public finances would intensify further, - in Italy, the increase in the NPL burden is equivalent to 10% of 2019 GDP - which in turn is likely to reinforce the sovereign-bank doom loop. Hence in countries that look set to register the sharpest increase in NPL ratios and already boast stretched public finances, the risk of a credit crunch is particularly high. Only in a protracted crisis scenario, in which Eurozone GDP still registers -22% below pre-crisis levels and the NPL ratio explodes to 18.0% - 25.4% by end-2021 – with one in four loans going sour – we think the pain threshold may be reached for policymakers to opt for an EU bad bank.

Avoiding a credit crunch should be the number one priority for policymakers in the short run but don’t forget long-standing structural issues. European policymakers are right to take unprecedented action to limit banks’ short-term pain in the current situation, given the sector’s pivotal role in supporting the recovery. But we see the risk that, in an ‘extend and pretend’ move, public support schemes and regulatory relief measures will simply be prolonged, but the underlying structural weaknesses of the sector remain unaddressed. Don’t forget that national elections are looming in Germany next year and in France in 2022, hence there may be little appetite to ‘lift the rug’ i.e. for a painful banking sector clean-up in the short-run. But such complacency to face reality comes at a non-negligible cost: Without greater policy ambitions, in bank-centric Europe nothing less than the region’s economic growth prospects are at risk, particularly as progress on a Capital Market Union remains largely elusive.

Figure 7: Relative performance Stoxx Europe 600 banks versus S&P 500

Senior Economist

Senior Economist