Historically, monetary and fiscal easing periods tend to be favorable for equity investors as equity tends to generate decent returns in periods of accelerating, but still manageable, reflationary pressures. From a pure fundamental perspective, it can be inferred that as long as the interest rate used to discount future profits rises less than the increase in inflation rates, the net impact of higher inflation on the present value of future cash flows should be positive. Of course, this direct inference assumes inflation as a positive contributor to earnings, that is to say in industrial companies CPI > PPI and that this triggers an acceleration in global consumption and in turn global growth. All in all, it means that as long as inflation is “benign” and that it remains outside tail values, be it “too high” or “too low”, it should support equities.

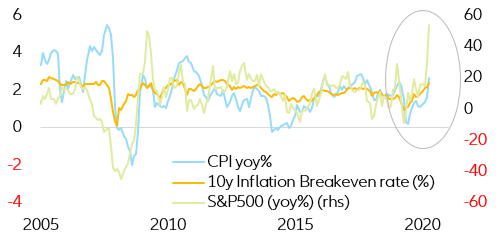

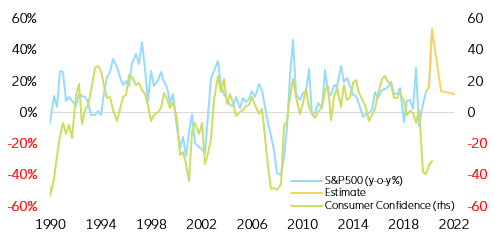

But is realized inflation the relevant metric? By simply eyeballing some inflation vs. equity charts, it can be derived that realized inflation rates, that is to say historical CPI growth rates, tend to lag behind market moves and are not coincident with abrupt market swings. This divergence is not only because of a publication delay but also due to markets front-running inflation. This suggests that the metric has a poor explanatory power for equity market returns from a tactical perspective (especially at the tails of the equity return distribution). Additionally, over long periods, one can observe an inverse U-shaped relationship between equity valuations and inflation rates, meaning that equity multiples tend to be low when inflation rates are “too high” / “too low” and they seem to have a sweet spot in between. This is especially true since extreme inflation scenarios tend to lead to elevated volatility as uncertainty skyrockets and market participants start pricing in a wider range of outcomes. This negative relationship at the tail, i.e. the more uncertain part of the inflation distribution bell curve, has been well documented through history.

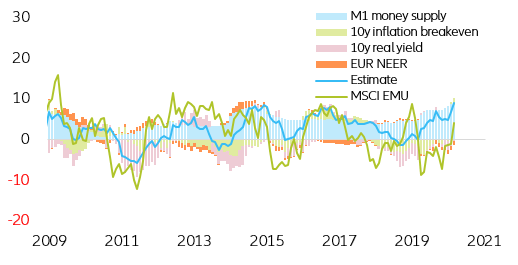

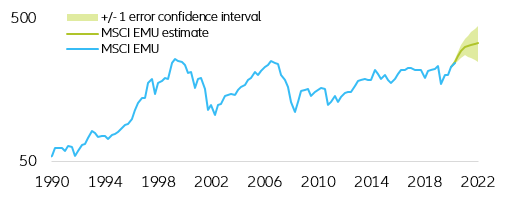

In this context, it is more appropriate to look at market pricing of inflation expectations as the embedded traded nature of this inflation measure makes it reactive to changes in investors’ expectations. With 2020 not being an outlier in this relationship, the extreme market swings in equity markets during the year and especially in 2021 have, as expected, coincided with changes in long-term market-based inflation expectations as market participants traded on increasing reflationary expectations (Figure 1).

Figure 1: US realized and market-based inflation vs equity (in % - y/y%)