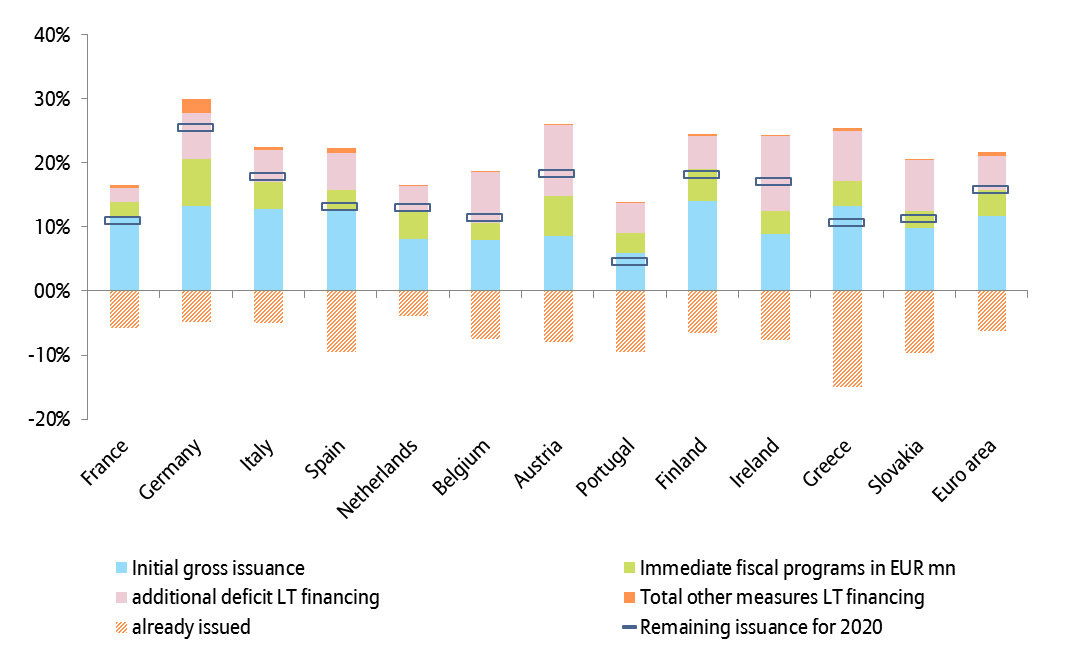

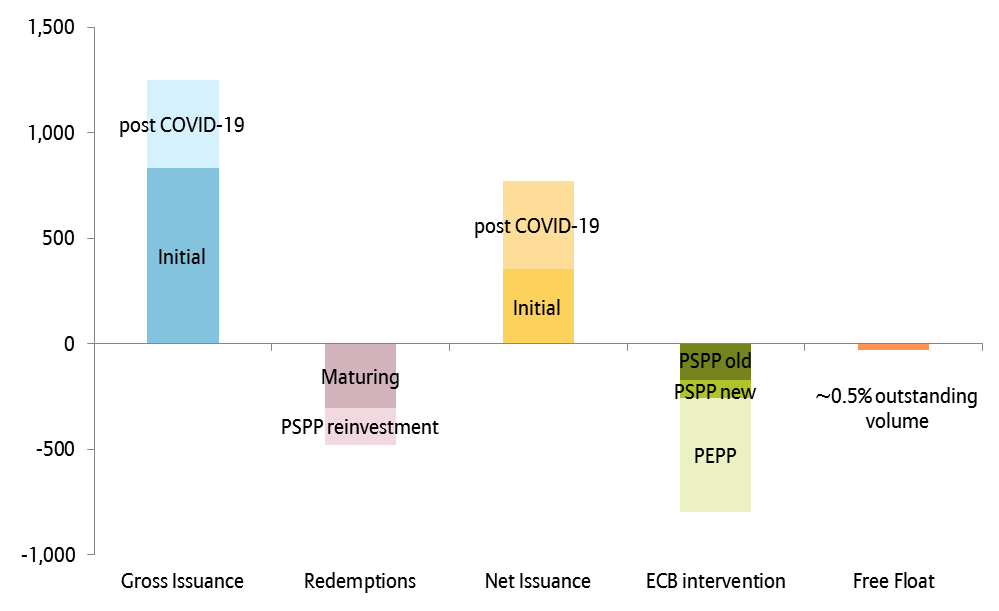

In response to the Covid-19 crisis, gross financing needs could amount to EUR800-900bn for the Eurozone, and only part of it will be covered by the issuance of long-term bonds. Next to state guarantees — depending on how much they translate into actual financing needs — these needs include discretionary spending (investments, tax cuts etc.), and additional expenditure on social security (automatic stabilizers). As a result, public deficits will increase. In Germany, we expect the deficit to reach 7% of GDP, in France 11%, in Italy 13.6%, and in Spain 7.8%. In addition, countries are expected to maintain their mix of short- and long-term funding: short-term debt instruments account for an average of 50% of total issuance in the Eurozone. The already revised funding plans of some sovereign debt agencies show a tendency to align the additional issuance of long-term bonds with the level of discretionary spending, while the planned issuance of short-term instruments seems to be more in line with the level of additional deficits linked to automatic stabilizers. Governments’ expectations of a temporary shock in 2020 followed by a significant recovery in 2021 contextualize the adopted strategy: to minimize the costs of transitory deficits using short-term financing. After all, the very short end of the yield curve is in negative territory for almost all euro countries.

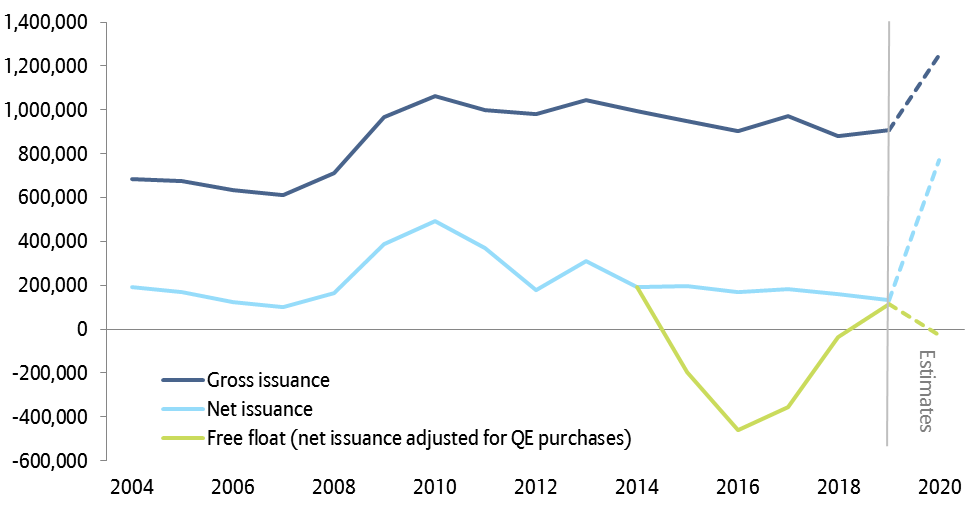

For this year we expect a gross issuance of long-term government bonds of EUR1250bn, of which EUR450bn are attributable to the Covid-19 crisis. This corresponds to an increase by 40% compared to last year and 50% compared to the initial funding plans. By the end of April, 35% of this volume had already been placed on the market, in line with the average completion rate of the last five years. Thus, despite the massive fiscal support programs, governments have not yet been tapping the bond market hastily. However, there are considerable differences between countries. Portugal and Spain in particular have engaged in significant frontloading, while Germany and Italy are lagging behind their usual issuing speed.

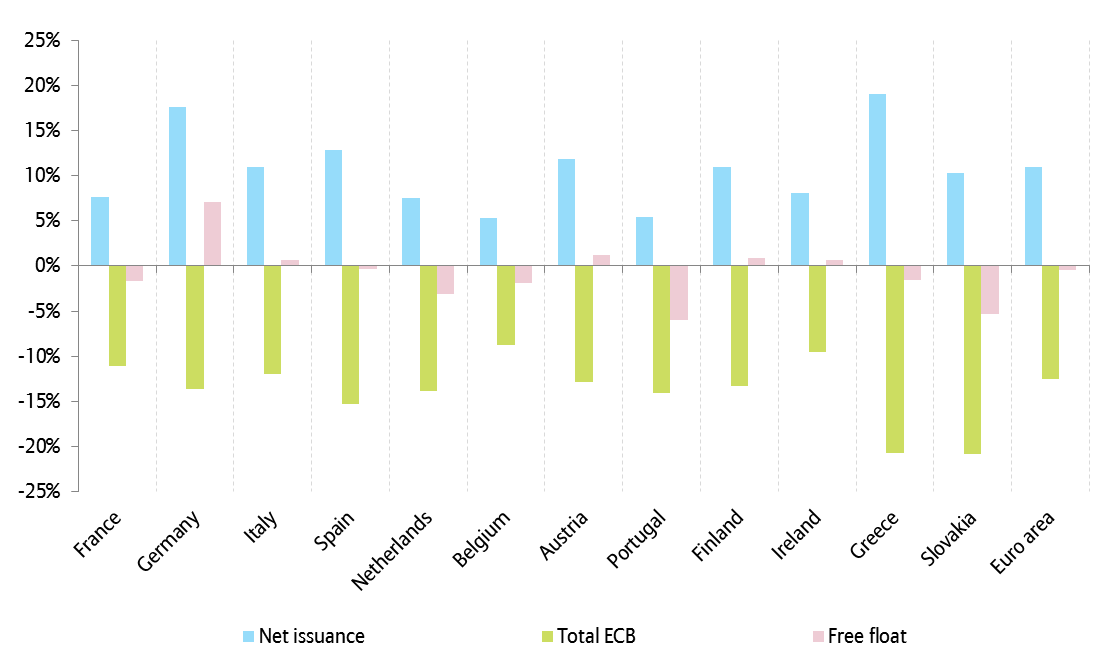

This massive increase in gross issuance might suggest a significant expansion in the supply of long-term euro government bonds. Indeed, after accounting for redemptions, the outstanding amount would rise by EUR770bn this year (net issuance). This would represent an increase of 11% of the outstanding volume. Again the situation varies greatly from country to country. While the increase in Germany and Greece is close to 20%, it is below 5% in Belgium or Portugal.

Figure 1 – Gross issuance of long-term government bonds in 2020

(estimates, in % of amount outstanding)