Executive Summary

- In response to the Covid-19 crisis, the debt-to-GDP ratio in advanced economies will rise to an all-time high of 130% of GDP this year. At the same time, long-term interest rates are at an all-time low.

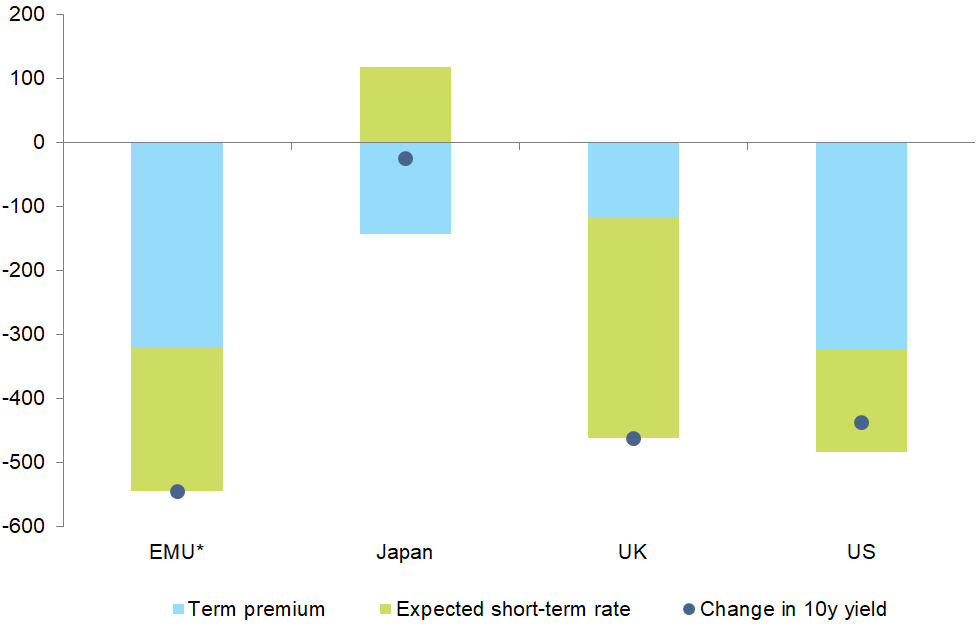

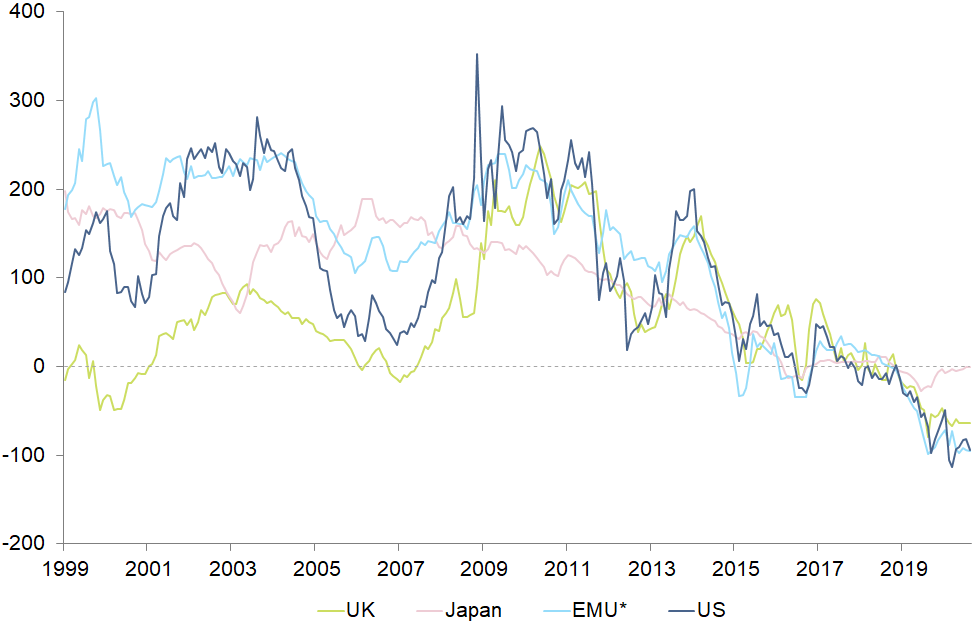

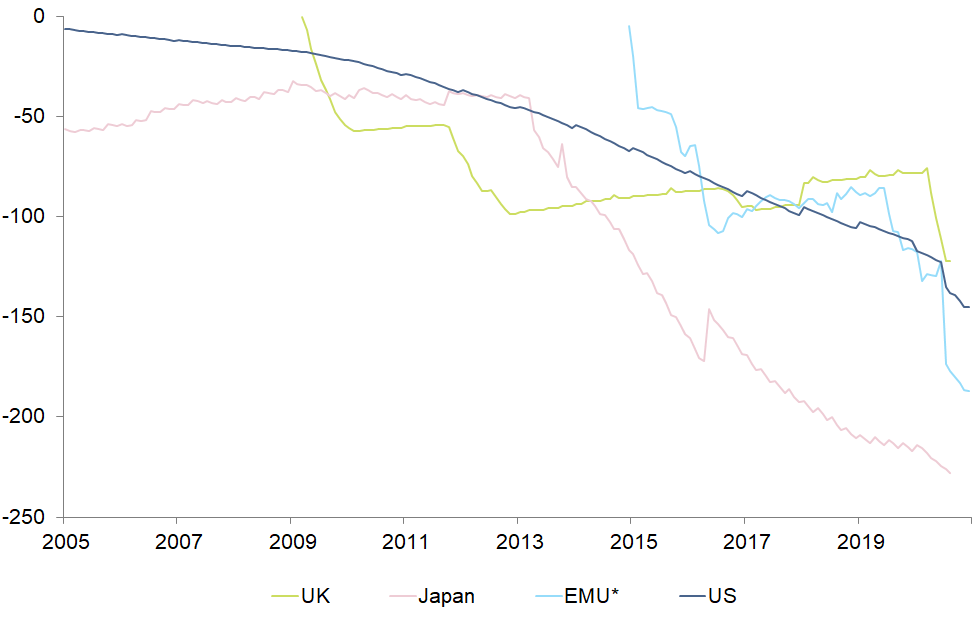

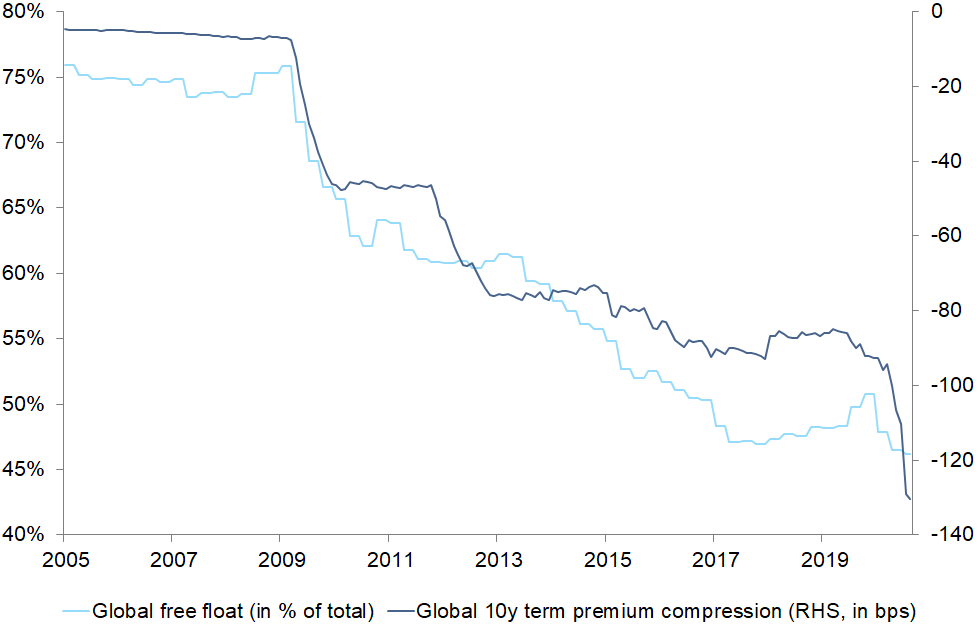

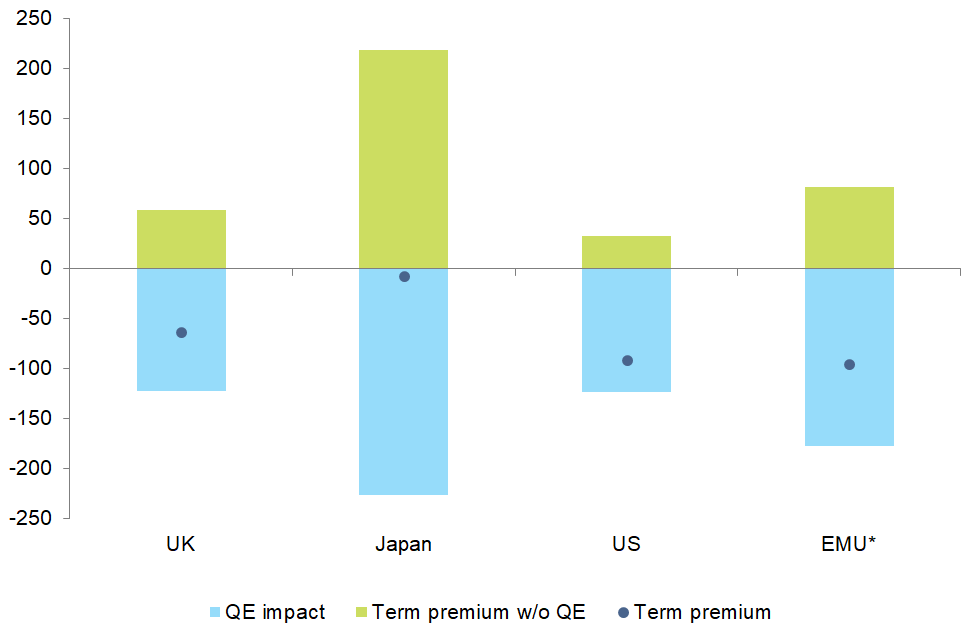

- The decline in long-term interest rates is due in large part to the fall in the term premium. This has now turned negative globally. For the 10y maturity, we estimate the global term premium currently at -60bps.

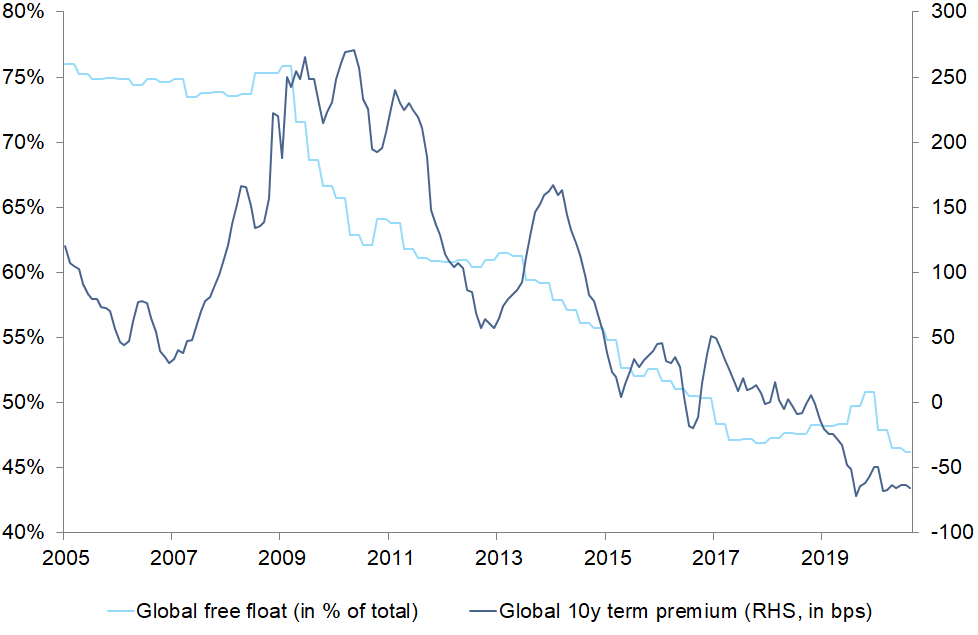

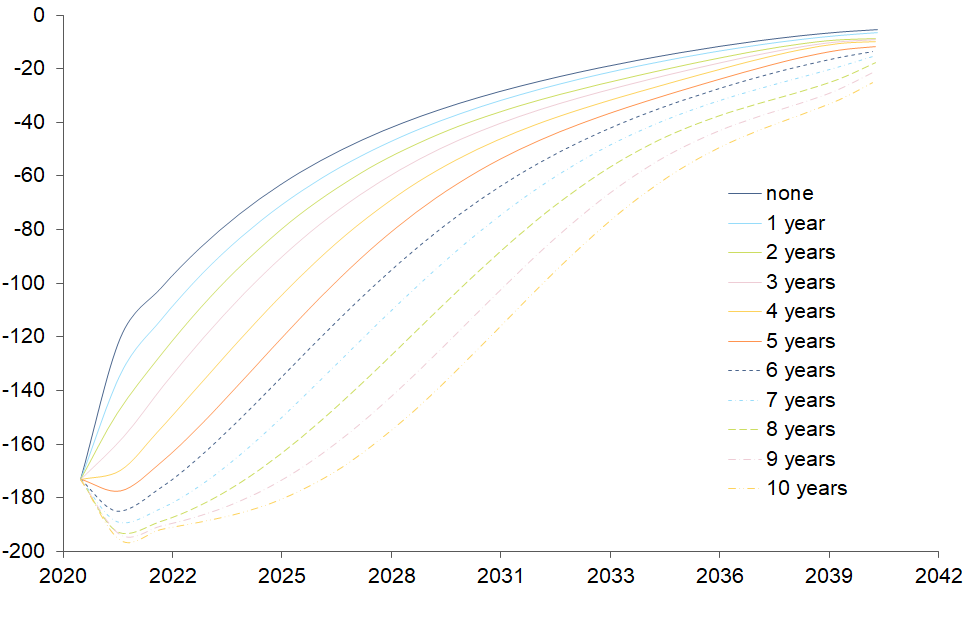

- The inversion of the term premium from a receivable risk premium to a payable safety premium is due to the amplification of unconventional monetary policy (especially Quantitative Easing). We currently estimate the global term premium compression by central banks at -130bps. Depending on the aggressiveness of the current QE programs, it could reach up to -200bps by the end of 2021.

- The yield-dampening effects of the term premium compression are long-term, since QE is followed by a phase of reinvestment.

- This environment presents several challenges for investors, including an increasingly hybrid risk profile of safe government bonds, which reduces their diversification characteristics to risky assets, and the increasing loss of return potential through carry.

- Possible responses are to compensate for the carry return with more duration (i.e. ultra-long bonds) or credit risk, or a more active management style to benefit from short-term dislocations on preferred curve segments.

A puzzle of premia - decomposition of nominal interest rates

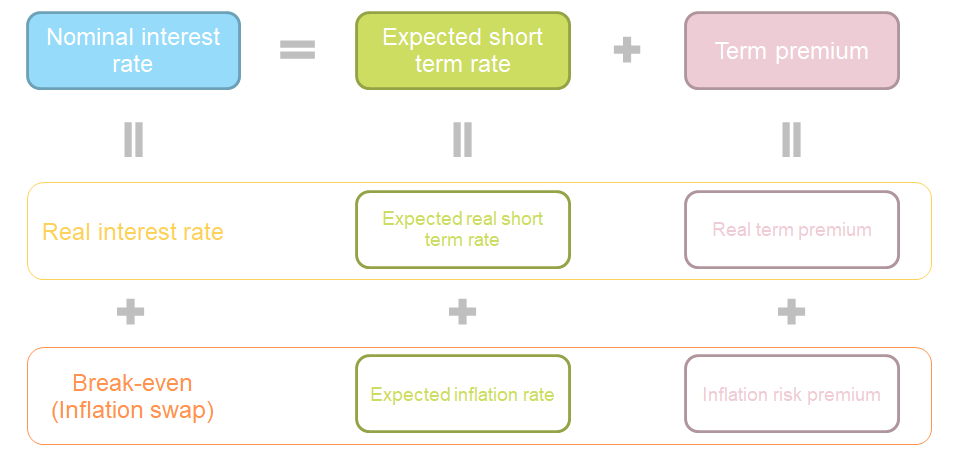

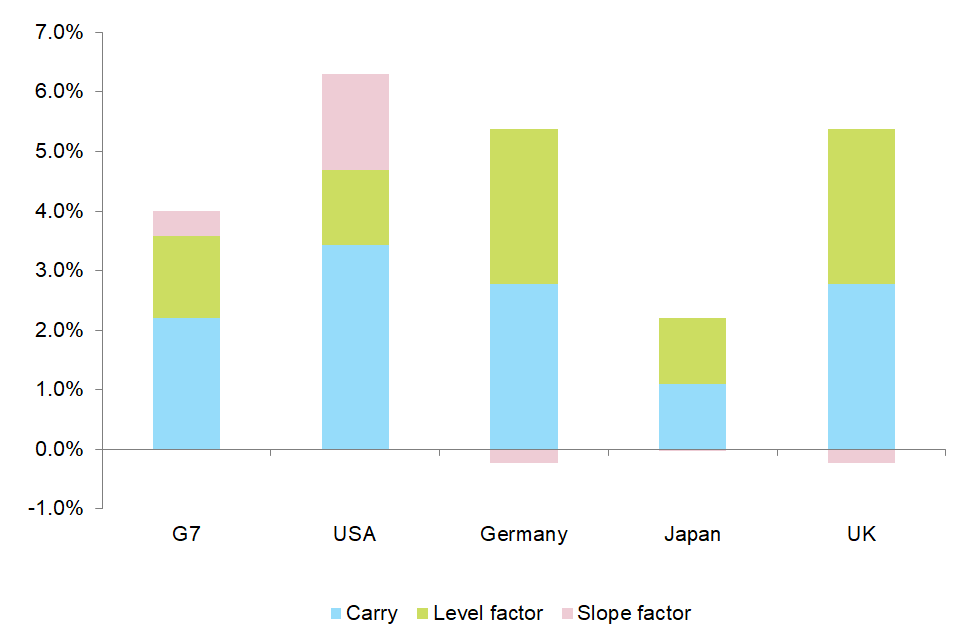

First, we have to break down nominal interest rates. We use a term structure model with two principal components: a level factor (expected short-term rate) and a slope factor (term premium) (see Figure 1). The term premium represents the investor’s risk reward for holding long-term bonds instead of a rolling investment in short-term interest rates. It is not to be confused with the simple steepness. The term premium is a risk premium that arises from the deviation of the actual term structure from a stylized term structure that reflects the so-called expectation hypothesis, which claims that yields on default-free government bonds should equal current and future short-term rates.

Figure 1: Term structure model – decomposition of nominal yields