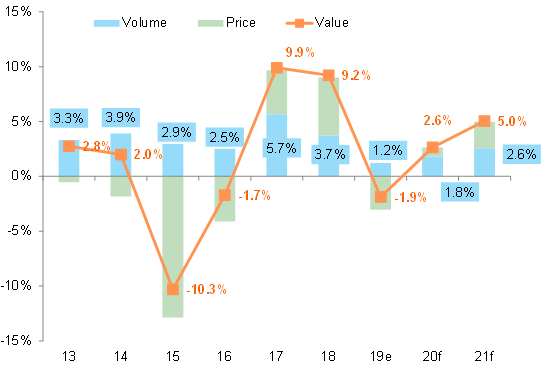

Domestic sectors will continue to outperform. The decoupling between supply and demand will prevail on the back of the very expansionary stance of monetary and fiscal policies, which primarily benefit domestic demand. Domestic-driven companies (services and construction for example) will outperform those companies generating profits abroad or relying on globally integrated supply chains. This decoupling will impact non-residential investment, which will turn out to be less resilient than consumption in developed economies, being exposed to protectionism and persistently high uncertainty. The U.S. elections in particular will incite companies to adopt a wait-and-see approach in 2020. The erosion of profits at a global level will explain this muted level of growth in investment and represents the main driver of another important move of decoupling, i.e. between fundamentals and market prices. We expect the automotive sector to stabilize in 2020-2021. However, any recovery in the automotive sector hinges on a revival of the Chinese market, which is experiencing a deep trough. A lack of outlook visibility remains for now. New significant disruptions of the car industry are likely. Like the car industry, other sectors are likely to suffer from increasingly tight regulations for the protection of the environment. The energy, steel, air and maritime transportation sectors are the most exposed to regulatory shocks.

We do not expect a shift in the low volatility regime as the dampening effect of unconventional monetary policy prevails. Political risk will remain the main volatility driver which implies a high probability of recurring short-term news related spikes. The divergent perception of risk between markets for risky assets and safe havens is likely to persist. On the one hand, risky assets, like equities, corporate bonds, emerging markets equities and bonds are not priced for a deterioration of current economic and political conditions. On the other hand, safe-haven assets like sovereign bonds in the developed world are not priced for an improvement of the economic and political environment (real yields are low or negative, inflation expectations remain stubbornly subdued). Against the backdrop of moderate but stable growth rates, continuing subdued inflation expectations, and dampening effects of unconventional monetary policy, the upward potential for yields on U.S. and euro government bonds remains limited. In a context of the wait-and-see posture of investors linked to the U.S. elections and progressive erosion of profits, the global equity market is expected to register an inflexion in its upward (monetary-driven) trend.

The Dollar depreciation (-4%) is expected to support EM assets. Low inflation, a monetary-based safety net for growth, a context of long-lasting low interest rates nurturing risk appetite and more fiscal support to come are pointing at an environment that is traditionally favorable to emerging assets. The latter could outperform in 2020.

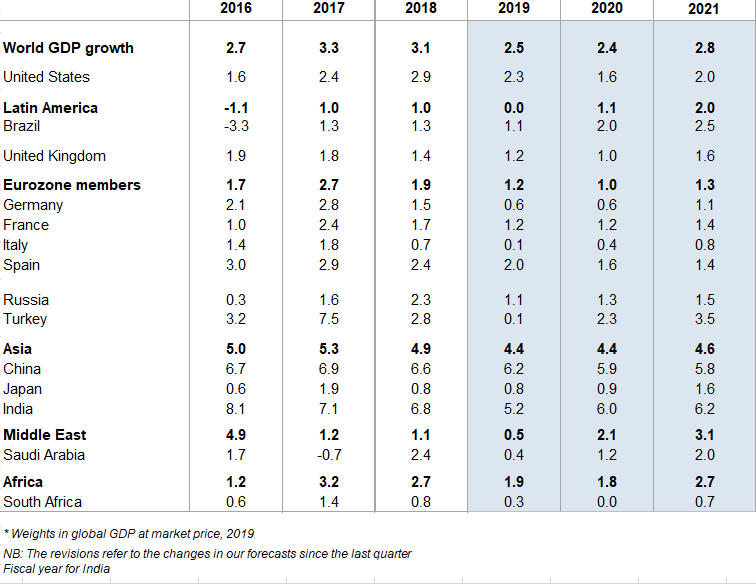

The economic environment will remain challenging across all regions

In the U.S., no matter the Presidential election outcome, more fiscal spending is likely

The resilience of the U.S. job market was an element of surprise to us in 2019 as we were expecting tangible signs of weakening in hiring intentions of manufacturers in particular, who were experiencing a significant deceleration of activity (the ISM manufacturing PMI has evolved below 50 since July 2019). Two elements can explain this resilience:

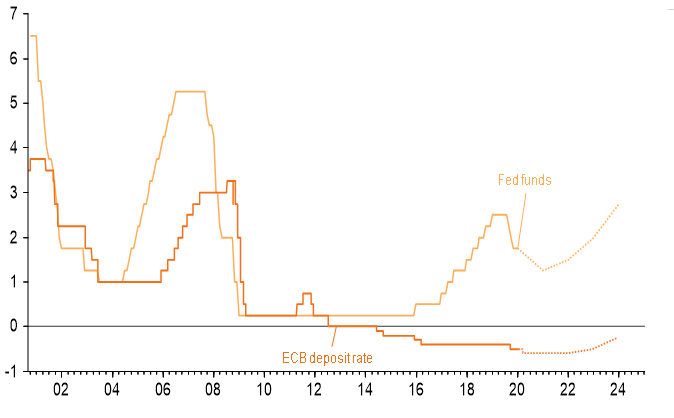

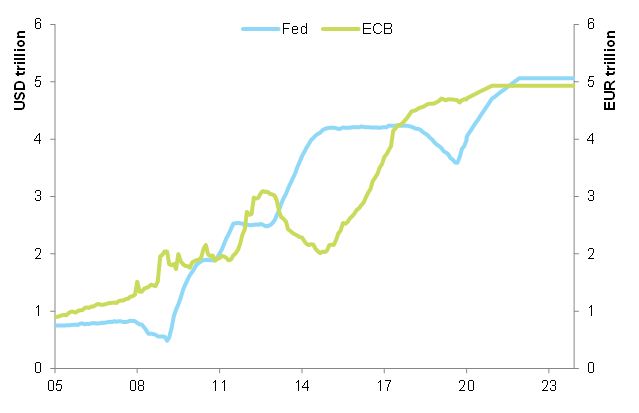

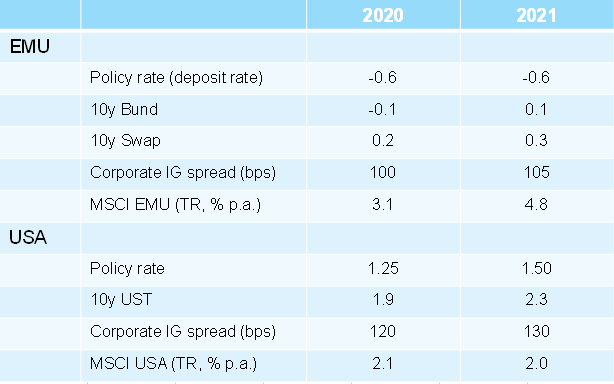

The Fed swiftly reacted to the shock of uncertainty by rapidly interrupting its cycle of monetary policy normalization (from the end of 2018), operating rate cuts as early as 2H19 and reinjecting liquidity from September 2019 onward. We expect one rate cut in March 2020 alongside a further deceleration of the economy. The Fed will adopt a wait-and-see approach thereafter. In 2H21, the Fed could implement two rate hikes when there is evidence of a stronger footing of the U.S. economy.

The fiscal policy represents another element explaining the resilience of the U.S. economy. Initially, we thought that the high degree of polarization in the U.S. political class was likely to trigger a government shut-down as the Congress is the final decider on budgetary issues. The opposite was actually true as Democrats and Republicans agreed on July 2019 on a bi-partisan agreement on higher caps for government spending. Instead of automatic procedures imposing severe reductions in fiscal spending, a supplementary spending amounting to USD300bn was agreed for the fiscal years of 2019 and 2020, neutralizing the debt ceiling constraint until mid-2021. From 2021 onwards, we expect even more expansionary initiatives on the fiscal side, which will maintain the U.S. deficit between -4.5% and -5.0% of GDP in the coming years.

This activism, currently visible at the level of U.S. economic policies explain why we a see a lower probability of recession in 1H20, even if we persist to think that growth will be particularly low at this time. We expect +1.6% in 2020 from +2.3% in 2019. In 2021, the macroeconomic scenario will be determined by the outcome of the 2020 Presidential elections. We attach for now a probability of 55% to a victory of a (centrist) Democrat, as President Trump’s economic policy turned out to be at the disadvantage of segments of his core electorate such as farmers (which insolvencies have rapidly increased following Chinese retaliations) and manufacturers, while mobilization of Democrats will be high. U.S. GDP growth should be back close to +2% in 2021 due to even more accommodation on the fiscal side.

The slowdown of the Chinese economy is not over

We expect GDP growth at +5.9% in 2020 and +5.8% in 2021, after +6.2% in 2019. Such growth rates should still allow the leadership’s goal of doubling 2010’s GDP by 2020 to be met. The policy mix is supportive, but the aim is to manage the slowdown, not reverse it. External trade should remain under pressure, given the still tense relationship with the U.S.. On the domestic side, we struggle to see positive catalysts. Consumers are facing a deteriorated labor market, and they are unlikely to receive another fiscal boost as in 2018-19. Infrastructure investment should continue to be supported by the fiscal policy, but the impulse in 2020 should be smaller than in 2019. Manufacturing investment growth is likely to continue moving sideways, as credit growth is only stabilizing. The housing sector, which has been the bright spot for most of 2019, has been showing signs of softness in the past few months. Housing policies have remained tight, as authorities seem more concerned about affordability.

The monetary and fiscal policies are likely to continue providing support to the economy in the coming year, but in a prudent way, given structural constraints. We expect 2.7% of GDP worth of fiscal support in 2020 (compared to 5.7% over 2018-2019), mainly through the increased quota of local government special bonds aimed at infrastructure investment. On the monetary side, we expect 30bp worth of cuts in the Loan Prime Rate, and 150bp worth of cuts in the Reserve Requirement Ratios. The bigger concern for the central bank in our opinion should be on financial stability: several bailouts this year have raised concerns regarding the Chinese banking sector, especially smaller banks. Pressure on these banks could in turn be transferred onto smaller companies and consumers in smaller cities, raising questions on the efficiency of monetary policy transmission.

Activity is showing signs of bottoming out in the Eurozone

There are increasing signs of green shoots in the Eurozone economy that suggest momentum will bottom out in the final quarter of 2019. Leading economic indicators, however, do not point to a sharp rebound. For one, industrial production will only see a gradual restart as inventory levels – despite an already notable correction – remain at elevated levels. Moreover, Eurozone export growth will only see a moderate pick-up as global trade momentum remains subdued and downside risks around trade and Brexit continue to loom large. Lastly, while cyclical headwinds may be gradually fading, structural challenges, including lingering protectionism but also the ongoing slowdown in Chinese GDP growth, will continue to weigh on Eurozone economic activity.

Just as unlikely as a swift v-shaped recovery, though, is a recession scenario for the Eurozone. We expect the consumer to save the day, thanks to the favorable labor market situation and robust wage growth. A fiscal bazooka is unlikely, given the relatively low recession risk, but a fiscal impulse to the tune of 0.5ppts should boost disposable income in both 2020 and 2021. Overall, domestic demand will nevertheless decelerate, thanks to a notable slowdown in investment activity as the recovery remains moderate and capacity utilization rates in industry are now close to or below long-term averages in most Eurozone countries. Overall, we expect GDP growth to register at +1.0% in 2020 and to only moderately pick up in 2021 to +1.3%.

In 2020, the ECB will remain under pressure to adopt a more accommodative policy stance as inflation – at 1.2% in 2020 and 1.5% in 2021 – will fail to reach the target of below but close to 2%, the economic recovery proves gradual at best and the Fed implements a further rate cut in H1. As political considerations around healing divisions in the ECB’s governing council make an increase in monthly asset purchases less feasible, we expect the ECB to opt for a further 10bp cut in the deposit rate to -0.6% in H1 2020. Monthly QE purchases meanwhile continue at the current pace of EUR20bn before being wound down by end-2020. In 2021, the more robust economic upswing and the ongoing increase in core inflation to 1.4% will allow the ECB to remain on hold under the assumption that the ECB’s comprehensive strategy review to be completed in late 2020 does not call for a higher inflation target.

Germany will remain the Eurozone laggard

Even though the German economy narrowly avoided slipping in recession, this is hardly any reason to celebrate. In view of the cautious outlook for global trade and the automotive industry and lingering elevated political uncertainty surrounding trade and Brexit, mini GDP growth rates at best can be expected in the coming quarters. Leading indicators point only to a tentative stabilization in industry so that the risk of another negative quarterly GDP growth reading or a technical recession remains elevated in 2020. Only the more pronounced acceleration in global trade in 2021 will put the German economy on a more robust footing. Domestic demand will continue to be the backbone of the German economy. Private consumption and investment in construction will remain key drivers of economic growth in 2020 and 2021, but gradually loose some steam in line with the slowing labor market. Fixed investment will largely stagnate in 2020 and stage a gradual recovery only in 2021 as export growth is picking up more markedly again.

Fiscal policy will remain very supportive, but a larger stimulus package is only likely if the German economy experiences a more pronounced setback. For both 2019 and 2020, we expect GDP growth of only +0.6% for Germany, and therefore about half the rate as for the Eurozone as a whole, after which GDP growth should rise to +1.1% in 2021.

The consumer will continue to drive France’s growth in 2020

In France, we expect fiscal support (additional EUR 9bn in 2020) to balance the impact of negative external (trade, low growth in Germany, Brexit) and domestic shocks (pension reform). All in all, GDP growth should remain stable at +1.2% in 2020 as in 2019, but with winners and losers. Household spending should increasingly drive growth but should be biased towards durable goods (housing, household equipment). The prolonged strike following the pension reform represents the biggest downside risk to our scenario as it would cost as much as -0.2pp of real GDP growth in Q1 if prolonged until March.

Growth dynamics in Italy will remain weaker than in the Eurozone amid fragile political stability

With economic activity bottoming out in Q1 2020, we expect real GDP growth to reach +0.4% over the whole year. With wage and employment growth losing momentum, the impulse from private consumption remains moderate. Investment has been surprisingly resilient over the year despite trade disputes und political uncertainty. But the investment cycle seems to have peaked now. As sentiment indicators remain at depressed levels and capacity utilization decreases, we expect lower GCFC growth in 2020. Thanks to their sectoral and geographical orientation (less China and UK, less automotive, more final goods), Italian exports proved rather resilient last year.

In 2020, however, this resilience might be challenged with external headwinds persisting, possibly spreading also to consumer goods. As to public finances, we still expect a rising debt-to-GDP ratio as average interest rates on government debt still exceed nominal GDP growth, while at the same time the primary surplus continues to be reduced. With the new coalition acting in a more conciliatory manner towards EU institutions, we do not expect a renewal of last year’s budget conflict. But given the fragile situation of the government coalition, political uncertainty is still going to weigh on economic activity in Italy. Although we expect the negative impact to weaken, political developments must be watched closely. The regional elections in Emilia Romagna taking place in the end of January will be the next critical moment.

In Spain, the new government would bring fewer business friendly reforms

After two elections and eight months of political deadlock in Spain, PM Pedro Sánchez was finally able to secure a simple majority in Parliament (by a margin of only two votes) and will now form a government.

We expect an improved outlook for consumer-oriented sectors and small companies, along with potential longer-term benefits from productivity gains due to higher spending on education. However, competitiveness will be reduced in the short term, and higher labor costs could indent profit margins (to below 40% of value added, down from a peak of 44.3%); in addition, we expect the construction and services sectors to be most negatively impacted by a higher minimum wage; banking and energy by higher taxes and the real estate sector by rent control.

In consequence, we still expect a gradual deceleration of GDP growth in Spain from +2% in 2019 to +1.6% in 2020 and +1.4% in 2021. Higher purchasing power due to accelerating salaries and social spending will be a modest buffer for private consumption, amid the slowest job growth since 2014 and an increasing savings ratio. Decreasing competitiveness in an uncertain global trade environment should slow exports. But significant progress on structural reforms and climate-related investment could help growth accelerate again in the medium-term.

The hardest is yet to come for the UK: the trade deal with the EU, and not before 2022. Mind pockets of volatility again!

In the UK elections, the Conservative Party won a solid majority of 74 seats - the party's largest since Thatcher’s election in 1987. This will allow them to “get Brexit done” in 2020, reducing the uncertainty in the UK economy. Risks of early elections are rather low in the next three years. As a result of lower uncertainty and higher fiscal spending, we revised on the upside our 2020 growth forecast for the UK from +0.8% to +1.0% and we expect growth to continue to recover into 2021 (+1.6%). Stronger domestic demand would be positive in a context of slowing company turnover growth. However, downside pressures on prices should prevail, given the still “above normal” levels of inventories post contingency stockpiling throughout the year. We expect business insolvencies to slow down to +3% in 2020, after +6% in 2019. In 2021, a moderate fall of -2% is likely. However, the hardest is yet to come: the trade deal with the EU is unlikely to be completed before 2022, given the challenges of implementing the border controls in the Irish Sea.

Emerging markets should see a stabilization in growth in 2020

Emerging Markets are still experiencing a growth slowdown, and this slowdown is broadening from export-oriented economies already hit by the trade recession to major EM such as India, Russia and South Africa. A prolonged growth slowdown is also highlighting political risk in many areas (Latin America, Africa, Middle East, Hong Kong). At the same time, lower inflation and a leeway to increase fiscal support are letting us expect growth stabilization in the next quarters. More dovishness in terms of economic policy is a pulling factor for capital flows, also attracted by high yields in frontier markets. However, this debt financing may well push debt ratios further to a level that is hardly sustainable in a subset of countries (Lebanon, Zambia, Angola, Argentina).

We expect Asia-Pacific GDP growth at +4.3% in 2019, +4.2% in 2020 and +4.5% in 2021

Soft global growth and the Chinese slowdown are still weighing on the region. There are also idiosyncratic factors at play. In Japan, the economy needs to digest the negative impact of the rise in sales tax implemented in October. The large fiscal stimulus announced in early December (1.7% of GDP of spending over 15-month) and a central bank ready to ease further if necessary should provide buffers. In India, growth has disappointed so far in FY2020, but the bottom should be behind us. The government should announce supportive fiscal measures that will help anchor the recovery. In the export-oriented economies, policymakers are reacting at different degrees. South Korea is proposing a record budget for 2020, while Hong Kong has announced supportive measures worth less than 1% of GDP. Taiwan expects a balanced budget in 2020, and Singapore has much room for fiscal support but has not announced concrete measures yet. In ASEAN, there is room for monetary support given relatively subdued inflationary pressures. Fiscal leeway is available in Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand but less so in Malaysia and Vietnam.

Annual GDP growth in the Emerging Europe region as a whole is forecast to pick up from +1.9% in 2019 to +2.1% in 2020 and +2.4% in 2021

There is limited monetary policy leeway in the region as interest rates are already low, except for Russia and Turkey, but most countries have fiscal policy leeway, given moderate budget deficits and public debt, and are likely to step up stimulus in 2020, if and as needed. As a result, there will be a divide between domestic and external demand, with the former being the main growth driver and the latter being affected by the still weak global trade environment. Growth in the 11 EU member economies will continue to moderate in 2020, as this sub-region is behind the curve, and stabilize in 2021. Turkey should continue its gradual but bumpy recovery path after the 2018-2019 crisis and recession, while annual growth in Russia will remain subdued at around +1.5%.

In Latin America, 2020 will be the seventh consecutive year of below 2% growth (excluding Venezuela). In 2020, weakness in investment should persist due to high political uncertainty, which hampers confidence and partially limits the transmission of monetary policy easing. The region is squeezed between investor demands for sound fiscal accounts and a continuation of reforms on the one hand, and consumers asking for social spending and redistribution on the other. While monetary policies have eased, there is little fiscal policy leeway to support growth overall. In 2021, while we see the recovery firming (+2.5%) due to higher global demand, risks could come from the U.S.’ monetary policy tightening. Countries where reforms will have stalled will be at risk.

Brazil’s outlook and risk picture is improving (+2% growth next year, after +1% this year) on the back of stronger domestic demand and exports that benefit from a lower exchange rate; higher business confidence after the pension reform approval and monetary policy easing should act as facilitators. While we expect a tax simplification law next year, the window of opportunity for reforms has narrowed. Mexico’s fundamentals remain sound, but growth is stalling (+0% this year, +1% in 2020), since domestic uncertainty halts the investment cycle. 2021 could be a pivotal year as the president prepares his “recall referendum” and legislative elections are scheduled. Argentina’s economy will contract again next year and risks will remain elevated for companies: the country should not avoid another default, and policies of the new government could fail to convince investors. In Chile, companies will face increasing risks as activity slows abruptly and 2020 proves a very busy political year. Expect more social protests, an uncertain business environment and a wait-and-see mode for investment. Lastly, Colombia’s social protests could slow activity and the recent constitutional blow to the center-right government’s tax reform should weaken business confidence

African economies will continue to experience in 2020 a protracted growth slowdown, particularly the biggest ones such as South Africa (+0%), Algeria (+0.5%) or Nigeria (+1%). In these commodity driven economies, a poor ability to reform has exposed the economy to a depletion of key outputs (mining, oil, gas, and power, depending on the economy). Overall, there is a high likelihood that country risk will deteriorate since subsidies will be increasingly hard to finance in deficit economies adding to difficulties already observed (Algeria, Tunisia, Sudan, and Zimbabwe). In all these economies, debt will increase and become high in some of them (Sudan, Angola, Zambia mainly) At the same time, long-term growth bonanzas will continue to support growth, such as increasing access to power particularly in West and East Africa.

Growth in the Middle East will pick up from just +0.1% in 2019 but remain subdued at +1.4% in 2020 and +2.1% in 2021. OPEC+ agreed oil output cuts are expected to remain in place throughout 2020 and will, combined with low oil prices, continue to curtail growth in the GCC. Even if we don’t expect a full-fledged war, The confrontation between Iran and the U.S. is likely to remain high over the coming months. Iran will remain subject to sanctions and in or close to recession in the next two years. Iraq and Israel should be the strongest economic performers in the region as new production facilities for oil and natural gas, respectively, will come on stream. Lebanon is stagnating and facing a prolonged political and economic crisis that could result in devaluation, rising non-payment incidents and a sovereign debt default over the next two years. Political risk is not abating and poses a significant downside risk to our modest growth forecast.