Executive Summary

- The unadjusted gender pay gap is a snapshot that shows the average differences in pay between all men and all women in the workforce. It stands at 15% in the EU. Reflecting mostly lower participation rates and shorter working lives, the unadjusted gender pension gap is more than twice as high.

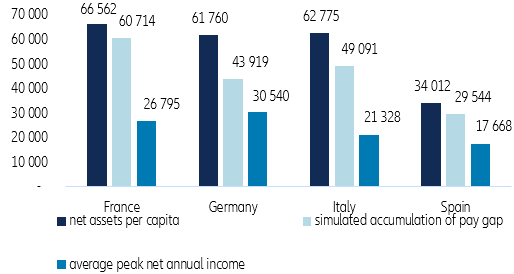

- If the shortfall in women’s income was invested in a 1% annual yielding safe asset over time, we estimate it could generate EUR45,410 on average at retirement age (EUR29,544 in Spain, EUR43,920 in Germany and EUR49,100 in Italy). In France, the sizable divergence in net income by age and gender mean that this sum could be as much as EUR60,714 for women at retirement age.

- In a context of a 3% yielding safe asset, these gender income gaps would amount to EUR71,500 on average in the EU; EUR73,000 in Germany; EUR51,300 in Spain and a hefty EUR94,300 in France, as well as EUR81,300 in Italy.

- Against this backdrop, policymakers need to level the playing field and equip women with initiatives such as raising the wage floor; promoting the return of women to the labor market after maternity leave with increased childcare facilities; longer shared parental leave and/or tax incentives and increasing the representation of women in political and economic decision-making positions.

The gender pay gap and pension gaps are a snapshot that show the average differences in pay between all men and all women in the workforce or in retirement, respectively. There are key factors addressed by the literature that have an influence on Europe’s gender pay gap: career preferences and overrepresentation of women in lower-paid jobs, the lower labor participation rate of women (EU-19: 66.2%) compared to men (77.2%) and shorter working lives (EUW:33 years, EUM: 38 years) due to maternity leave and/or work interruption. Additionally, there is a persistent and uneven concentration of women and men in different sectors in the EU: Three in every ten women work in education, health and social work (compared to 8% of men), which are traditionally low-paid sectors. On the other hand, almost a third of men are employed in the traditionally higher-paid sectors of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM), compared to 7% of women.

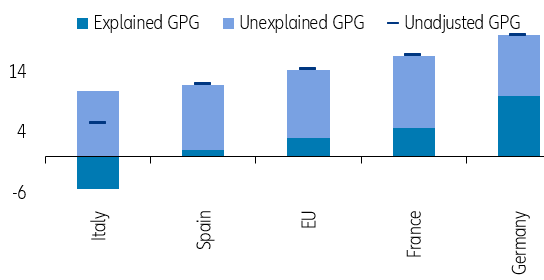

Work and investments by the EU have been implemented to study and measure these so-called “explained Gender Pay Gaps” (see Figure 1). They do not, however, account for the entire pay gap; the so-called “unexplained” factors include statistically unobserved wage determinants of the gender gap such as personal ability, negotiating skills and institutional settings.

Figure 1 – Explained and unexplained parts of the unadjusted gender pay gap (%)

The aim of this paper is to illustrate the economic consequences of these unadjusted income gaps between men and women during their lifetimes in a user-friendly manner. It is not meant to analyse the complex causes that are also complex to disentangle without micro-data.

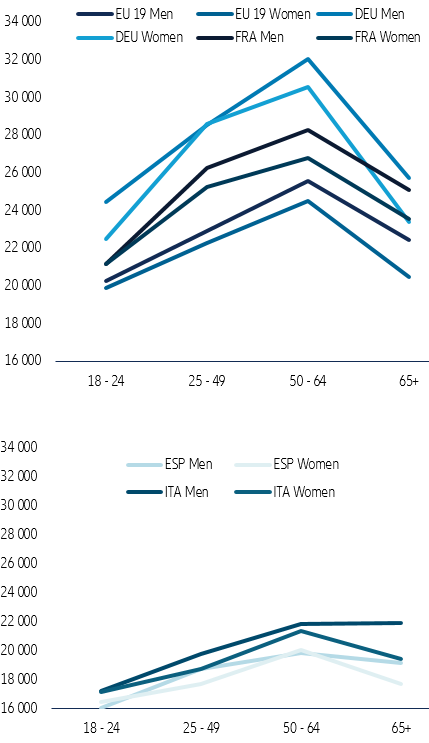

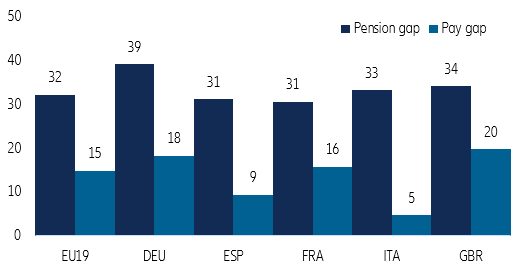

The unadjusted gender pay gap stands at 15% in the EU. Reflecting mostly lower participation rates and shorter working lives, the unadjusted gender pension gap is more than twice as high. Eurostat provides estimates for average net income by age and gender, which we use to draft an average net “lifetime” income profile (see Figures 2 and 3). We find that in most most countries early career income is remarkably similar for both men and women. However, experience and age – on average – mostly pays off for men, as the gap only widens for women. As their careers progress, women start to see a wider income gap, which peaks in the years between 50 and 64. Whether at the core of this issue there is industry choice, maternity or bias, women are systematically earning less than men; living costs, however, are the same for both.

Somewhat surprisingly, Spain and Italy have a lower-than-average pay gap, but this is largely due to the relatively low employment-to-population rates of women (Spain: 56.6; Italy: 49), who are primarily responsible for childcare and elderly care – as well as unpaid work within households. Where women are employed, it is predominantly in skilled occupations with high pay, leading to a smaller pay gap. In other countries, such as Germany, more women work, but often only part-time .

Moreover, women’s working lives are markedly shorter so when reaching retirement age they have less pension contributions, which leads to net income (or the net income pension at this stage) falling steeply compared to men at retirement age as this figure also includes welfare pension benefit for those that didn’t engage in paid labor. This explains the much bigger pension gaps in all countries (see Figure 5). In Spain and Italy, with their low participations rates, the difference between pay and pension gaps is particularly high: In Spain, the latter is more than three times as high; in Italy more than six times.

Figure 2 – Mean net income by gender and age

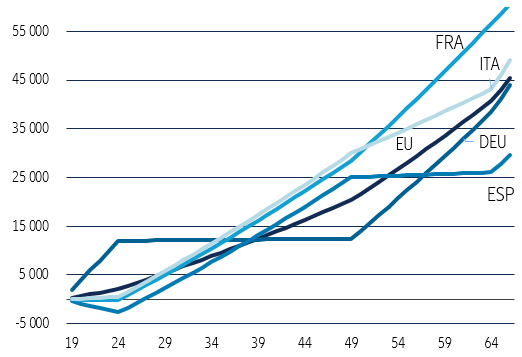

If the shortfall in women’s income was invested over time, we estimate it could generate at least EUR45,410, per woman in the EU. In France, this sum could go up to EUR60,714. To illustrate the shorfall in lifetime income, we run a simulation in which we use the average nominal net income gap between men and women by age. We use a simple compound interest scheme in which we assume an interest rate of 1% compounded annually. This is a very modest discount rate for annual income but it is based in an average bond yield in the EU. With the lifetime earnings’ income profile, we find that if women in the EU-19 were to invest this “income gap” – that they don’t perceive – in a safe asset that yields 1% annually from age 18 until they reach retirement, they would accumulate EUR45,410.

Women in Germany, following this “investment scheme” and taking into account the years that they earn marginally more than men, would have an accumulated lifetime income of EUR43,920 when they reach retirement age. In Spain, as incomes are generally lower for both men and women, at retirement age, they would accumulate EUR29,544 on average.

Women in France start off their careers earning more than men but this quickly shifts and the pay gap widens with age. The difference is so large that if women were to invest this “male bonus” they would accumulate EUR60,714 by the age of retirement.

In Italy, as in Spain, incomes are on average lower than in Germany or France, but even so the gender gap in almost 50 years of working, if invested at 1% annual yield, would mean an additional EUR49,100 at retirement age.

Figure 3 – Pay gap accumulated account for women through the years

In France and Italy, the pay gap translates into around 2.3 years of peak average net income for women. In Spain, the pay gap is around 1.7 years of peak average net income, while in Germany this figure is 1.4. Figure 4 shows our simulation of pay gap accumulation compared to the net financial wealth per capita in each of these countries.

If, however, these gender income gaps were invested at the highest range of safe asset investment (3%), the difference over their careers would be much higher – EU-19: EUR71,500; DEU: EUR73,000; ESP: EUR51,300; FRA: EUR94,300; ITA: EUR81,300.

Figure 4 – Pay gap accumulated account for women

Policymakers need to level the playing field and equip women with as many tools as possible to be as financially and economically resilient as their male peers. These huge accumulated gaps (see Figure 5) suggest that despite herculean efforts to bridge pay gaps in the EU, including paid maternity leave and increased investment in remuneration frameworks, the average inequality of women in the labor market comes with a sizable cost. They contribute to the heightened vulnerability of women in times of income shocks, i.e. unemployment, retirement, pandemics – and even wars. To avoid every recession becoming a she-cession, policymakers need to continue with their efforts to close the gender pay and pension gas,p which could also close the output gap and give a very necessary boost to the economy.

Figure 5 – Gender pay/pension gaps

To promote equal pay, reforms could focus on different areas: Firstly, raising the wage floor – as women are often overrepresented on lower paying jobs and industries, and this would set a minimum standard when compared to the median wage . Secondly, promoting the return of women to the labor market after maternity leave with tried and true measures such as increased childcare facilities, longer shared parental leave, and/or tax incentives. And finally, increasing representation of women in political and economic decision-making positions. Employed women hardly make it to the top: Women accounted for 7.8% of board chairs and 8.2 % of CEOs in the fourth quarter of 2020, according to the EU Commission. Increasing representation of women in leadership positions can help reduce up to 10% of the gender pay gap as manager wages are found to be almost twice that of other employees (in the US).