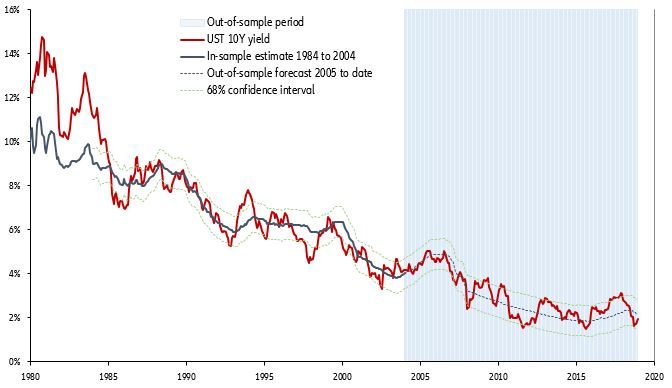

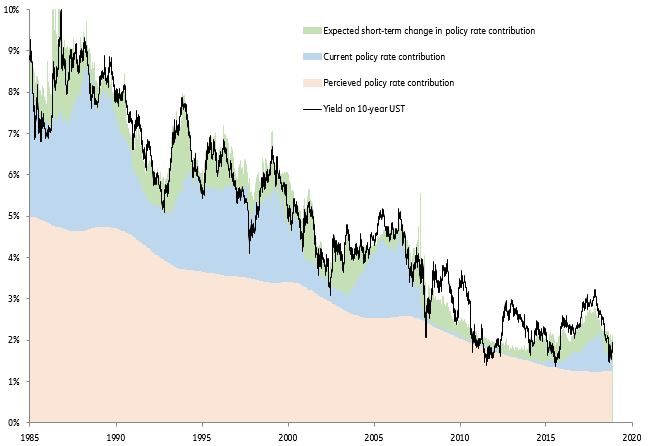

- Long-term nominal bond yields reflect expectations about the future course of policy rates. However, whether these expectations are adaptive or rational, backward- or forward-looking is at the heart of the matter. While there is robust evidence that long-term adaptive expectations are in the driving seat, we find that short-term rational expectations contribute to fluctuations around the trend.

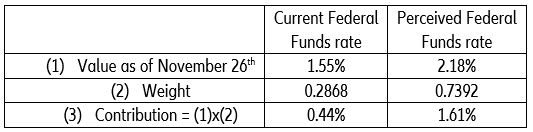

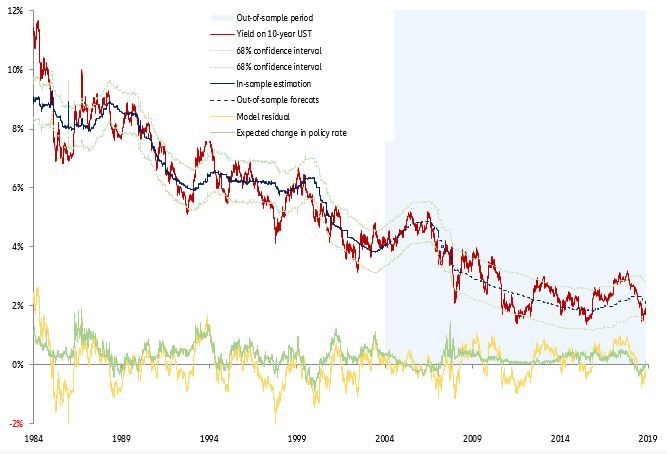

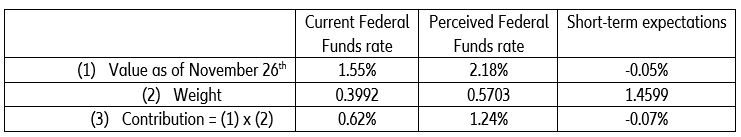

- We present an enhanced model that combines these two types of expectations, allowing us to assess what is already priced in long-term bond yields. As of 26 November, the estimated fair value of 10-year U.S. treasury bonds is 1.79%. Our model shows that 0.62% of that is contributed by the current Federal Funds rate, 1.24% by its perceived value and -0.07% by its expected short-term change (against -0.50% in early September). In other words, long-term adaptive (or backward-looking) expectations about policy rates keep short-term forward-looking expectations on the leash.

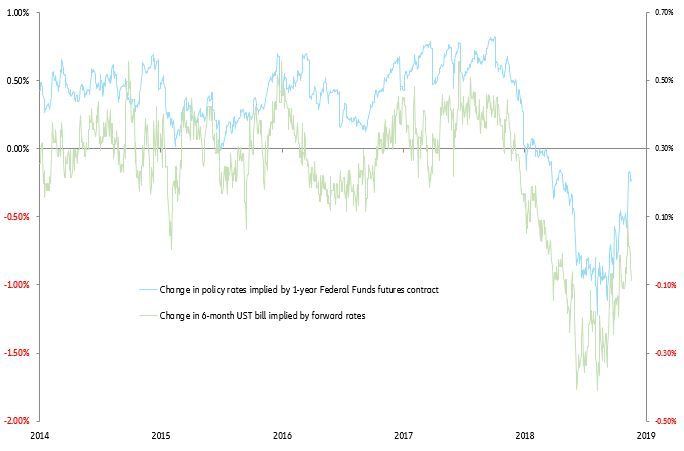

- This was seen in early September, when, having very much bought the rumor that rate cuts were coming, the U.S. bond market sold the news when the FOMC actually cut the Federal Funds target. Expectations about the FOMC’s next moves are now subdued.

- From a valuation point of view, our enhanced model confirms that the distribution of potential outcomes is now not skewed enough to warrant an aggressive positioning of portfolios in terms of duration.

For investors, one challenge is to forecast the future path of monetary policy. Quite another and a perennial one is to assess what is already priced into asset prices, especially bond prices. To answer this question, we look at the case of U.S. monetary policy and the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasuries. There are three reasons for this choice: Firstly, because of the role of the USD in the international financial system, U.S. monetary policy has a global reach and impacts all asset classes. Secondly, over the last year or so, speculation about the Federal Reserve’s next moves has been particularly rife. Finally, if, after many years of unconventional money policy, the Fed reverts to business as usual, its policy rates will again become its key policy tool.

To assess what is already priced in bond yields, we introduce an original analytical framework that blends forward-looking “rational” expectations with backward-looking “adaptive” expectations. We find that the latter trumps the former and keeps them on a leash, suggesting that the current consensus about the course of monetary policy in the next twelve months has little impact on long-term nominal bond yields: In sharp contrast to recent episodes, bond yields are not overly distorted by extreme expectations of tightening (as in October 2018) or of easing (as in September 2019). As a result, this situation does not warrant an aggressive positioning of portfolios in terms of duration.

Long-term nominal yields reflect expectations about the future course of policy rates

Developed capital markets offer fixed income investors a choice between instruments of different maturities and redemption yields. For example, the yield on a 10-year U.S. Treasury bond (1.74% as of 26 November, 2019) is typically different from the yield on a 1-year U.S. Treasury bill (1.59% at the same date), which is in turn typically different from the Federal Funds target rate, set by the Federal Reserve (1.75% at the same date). He who buys a 10-year UST bond today and intends to hold it until maturity locks in a 1.74% rate of interest until November 2029. This only makes sense if, right or wrong, he expects this 1.74% rate of interest to be at least equal to the average Federal Funds rate over the next ten years. If he does not expect this to happen, he is better off keeping his money in an overnight deposit, hoping that the reinvestment risk will benefit him.

But are such expectations rational or adaptive?

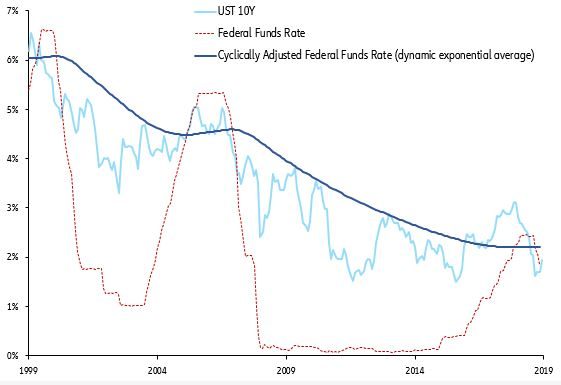

The buyer of a 10-year bond is therefore supposed to have an informed idea about the average level of short-term rates over the next ten years. Obviously, in the current state of our knowledge, this is out of reach. Hence, investors have a plan B: Keynes would say they use a valuation convention, which is to assume that the future will look very much like the past, subject to some adjustments reflecting the surprises that inevitably occur. Like it or not, the nominal yield on 10-year U.S. Treasuries is much more correlated with some historic average of the Federal Funds rate than with its current level. Put differently, long-term rates exhibit much more inertia than short-term rates, even when the Central Bank is quite explicit about its next moves. A case in point, shown in Figure 1, is what has come to be known as Greenspan’s conundrum. In February 2005, after the Fed had been hiking rates by 150 basis points in the nine months since June 2004, Alan Greenspan, the then Chairman of the Federal Reserve, found it puzzling that long-term bond yields had not risen or even fallen.