Executive summary

- Market-based long-term inflation expectations – as revealed by index-linked bonds or inflation swaps – tend to concur. They are meaningful because capital markets participants are incentivized to price them as accurately as possible: more directly than other agents, they have skin in the game.

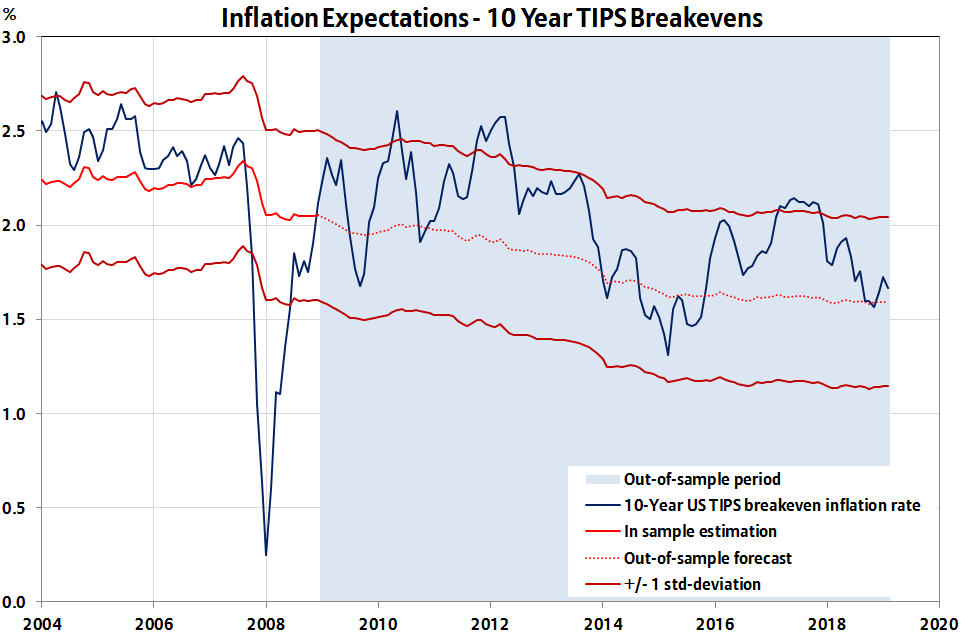

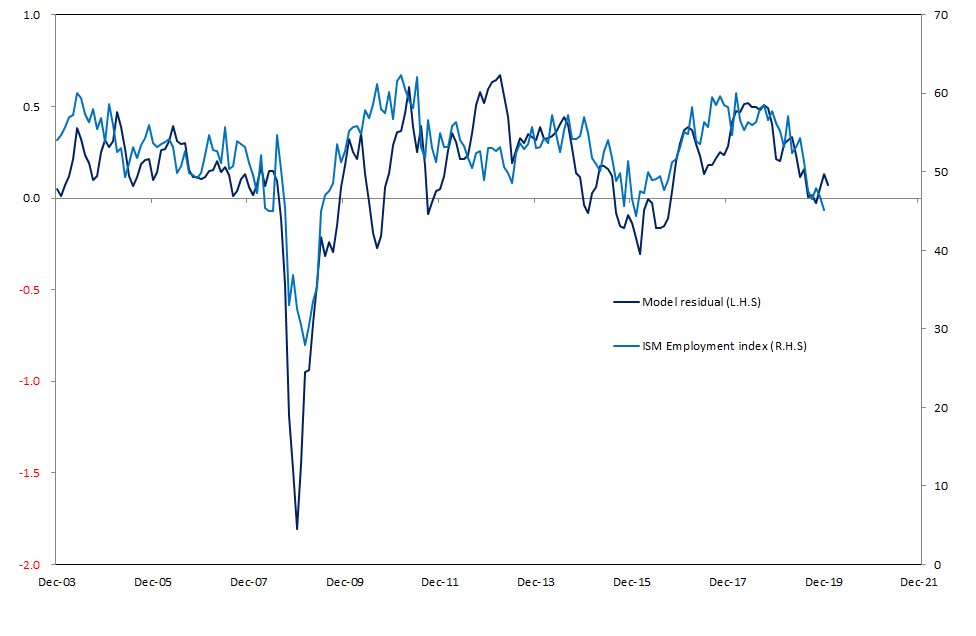

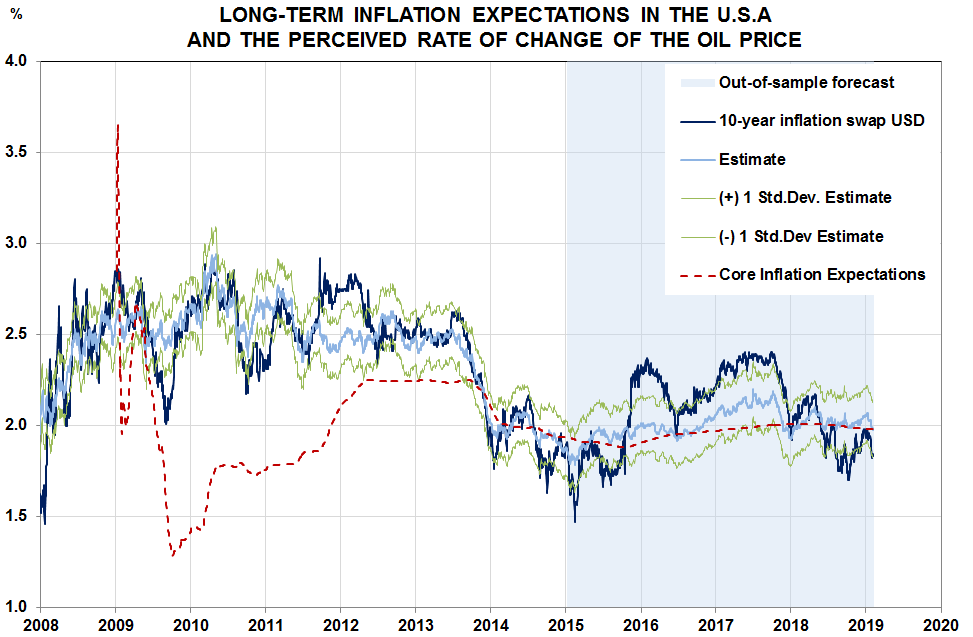

- Market-based inflation expectations have two components: on the one hand, a long-term, adaptive (or backward looking) component, which is linked to the perceived (or cyclically-adjusted) rate of inflation and, on the other hand, a short-term, rational (or forward-looking) component, which can be proxied mainly by the ISM employment index and secondarily by the oil price. As the adaptive component exhibits some inertia, it holds both the rational component and inflation expectations on the leash.

- At their current level, which is close to fair value, inflation expectations no longer present investors with any kind of safe bet. For this to happen again, transient cyclical forces must first pull them away from fair value.

- As the cyclically-adjusted rate of inflation is currently rather inelastic, it would take quite a dramatic and persistent inflation surprise to have a material, structural impact on market-based inflation expectations. Given the current low elasticity of the anchor of market-based inflation expectations and the stability of core inflation expectations, any tightening of monetary policy is likely to be cautious.

Inflation expectations matter

Inflation matters for at least two reasons, first, because it forces transfers of wealth between debtors and creditors, second, because - by blurring the information contained in relative prices - it makes economic calculus more difficult. But, inflation expectations matter even more, because they are liable to reinforce any inflationary process by altering people’s behavior.

Extreme conditions, be it acute deflation, like in the US during the Great Depression, or hyperinflation, like in Germany in the early 1920’s, or stagflation, like in the 1970’s, provide us with a magnifying glass: they highlight how expectations of rising or falling prices can amplify inflationary or deflationary dynamics through positive feedback loops.

This explains why inflation expectations nowadays play such a central role in the conduct and explanation of monetary policy. Knowing that Central Banks pay attention to inflation expectations, financial markets also do so.

But this is easier said than done, for inflation expectations are not directly or easily observable. Nor is it straightforward to understand what drives them. The purpose of the present investigation is to shed some light on these two issues.

Inflation expectations are best revealed by those who have skin in the game

Initially and for a long time, surveys have been the only way to gauge people’s inflation expectations. But the answer given to a survey very much depends on how questions are asked. Furthermore, people don’t necessary put their money where their mouth is.

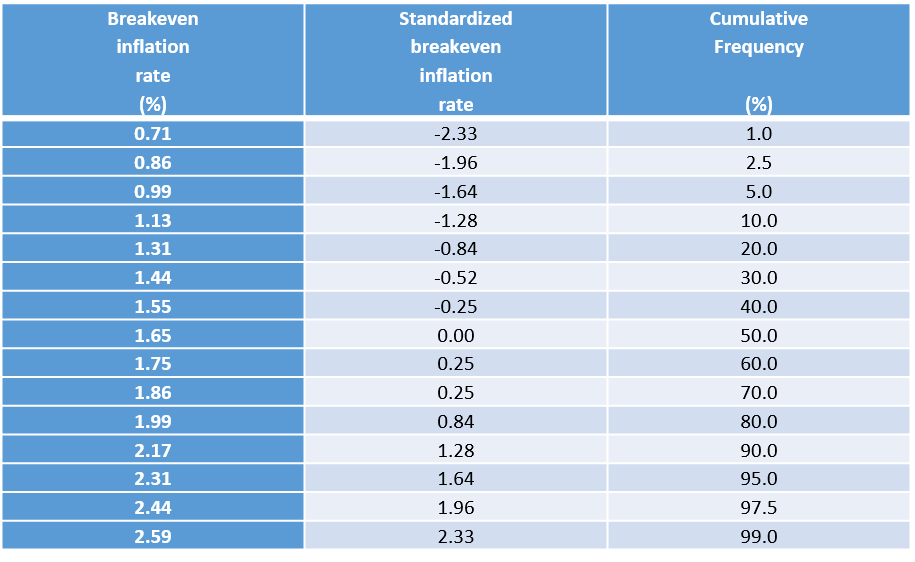

These are two strong reasons to turn to financial markets, more precisely to inflation-linked bonds, to elicit inflation expectations. Such bonds, also known as linkers, are indexed to inflation so that the principal and interest payments rise and fall with the rate of inflation. In them are embedded implicit market-based inflation expectations, which one can derive from an arbitrage relationship between bonds bearing a fixed nominal rate of interest and inflation-linked bonds. The breakeven inflation rate is indeed the difference between the yield of a nominal bond and an inflation-linked bond of the same maturity. For example, the nominal yield on a 10-year UST is (at the time of writing, i.e. January, 31st, 2020) 1.52%, while the indexed or real yield on a 10-year UST linker is only -0.14%. For the linker to return as much as the nominal bond, inflation must run on average at at least 1.66%a year (=1.52-(-0.14)) over the next ten years. The breakeven inflation rates are very much the same across maturities.

So far, so good. But what if nominal yields or real yields happen to be distorted by some structural factors? Couldn’t these breakeven inflation rates be biased in one direction or the other?

Market-based inflation expectations concur (more or less)…

A worrywart might argue that quantitative easing (QE, i.e. the purchase of nominal bonds by Central Banks) artificially depresses nominal yields. Everything else being equal, quantitative easing would then lower market-based inflation expectations. In plain English, Central Banks would be using a biased weighing scale, could even be tempted to stack the deck, market-based inflation expectations would systematically underestimate inflation expectations. Another worrywart might also argue that, the linkers market still being a rather small one, there is a scarcity or liquidity premium in the linkers’ real yield that artificially depresses it. At least partially, this scarcity would offset the impact of QE.

That the linkers’ breakeven inflation rates should be taken with a pinch of salt is suggested by another, newer category of financial instruments, namely inflation-linked swaps. In an inflation swap, one party pays a fixed rate cash flow on a notional principal amount (the swap rate), while the other party pays a floating rate linked to an inflation index. The latter bets that future inflation will remain below the swap rate. Like in any other swap transaction, an inflation-linked swap involves a limited use of liquidity. The pricing of an inflation-linked swap is therefore less liable to be distorted by QE than that of a linker. Across maturities, the inflation-linked swap rates are currently 20 bips higher than the breakeven inflation rates.

Most importantly, breakeven inflation rates and inflation swap rates have been strongly correlated ever since these two types of instruments have coexisted: in other words, up to an almost constant spread of 30 +/-7 bips, they have been telling the same story in terms of market-based inflation expectations; while their levels have always slightly differed, they have always moved in the same direction and with the same intensity.

… but err more often than not

What does this mean? It means that the relevant question should not be the quest for a perfect measurement of inflation expectations, for it is probably impossible to design. The relevant question is rather to understand what drives the long-term as well as the short-term movements in the somewhat noisy measurements of inflation expectations that financial markets provide.

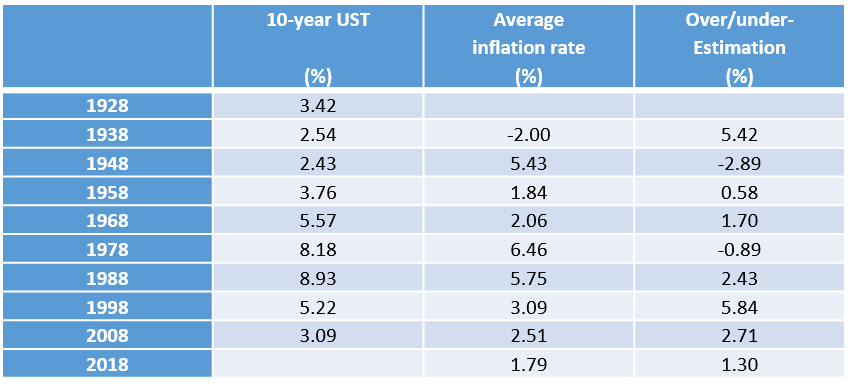

Let us start with the long-term movements. In theory, the buyer of a long-term bond, say a 10-year bond, should have an informed idea of the average inflation rate over the next 10 years. Hence, at the very least, the nominal yield on the 10-year UST should at any time be reasonably higher than the average inflation rate observed during the 10 subsequent years. As shown in Table 1, this has rarely been the case during the last nine decades. To take two extreme and opposite examples, in December 1938, the yield on 10-year UST was 2.54%, while the average inflation rate between 1938 and 1948 turned out to be 5.43%, leaving investors with an ex post negative inflation surprise of -2.89% a year. Conversely, in December 1988, the yield on 10-year UST was 8.93%, but the average inflation rate between 1988 and 1998 was only 3.09%, leaving investors with a positive inflation surprise of 5.84% a year.

In other words, the historical record shows that bond markets have done a poor job at forecasting the long-term trend in inflation. This should not be surprising, because inflation is not a risk, not an unknown unknown; it rather is an uncertainty, for we don’t know what cannot happen five, ten, twenty years out.

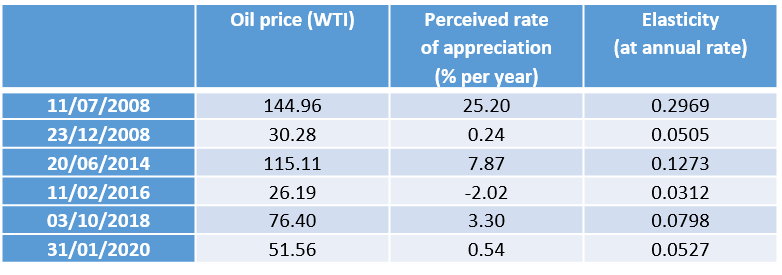

Table 1