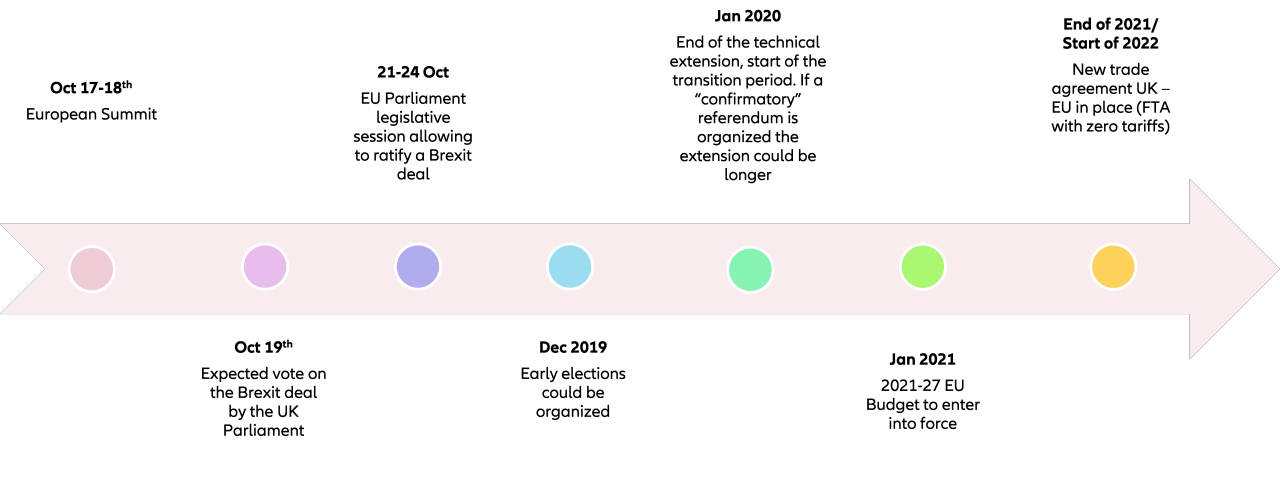

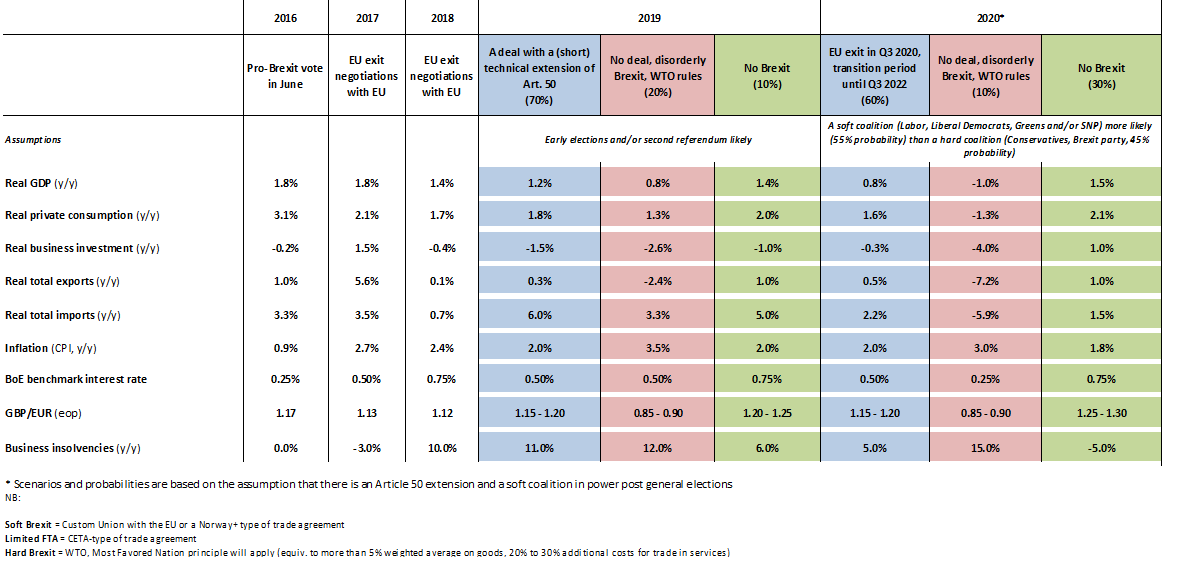

- A Brexit deal with Europe, but limited time for ratification could require a (short) technical extension. On 17 October, the European Commission and the UK government managed to agree on changes to the Withdrawal Agreement and the Political Declaration ahead of the EU Summit. The Heads of State need to approve it (likely) before it is ratified by the UK Parliament on 19 October (tough but not impossible) and by the EU Parliament next week during the plenary session (likely). The deal lowers the uncertainty (-0.3pp of UK real GDP growth per year since 2018), and should progressively help the UK return to “business as usual”. However, mind the risk of early elections by the end of Q1 2020 and/or a second Brexit referendum.

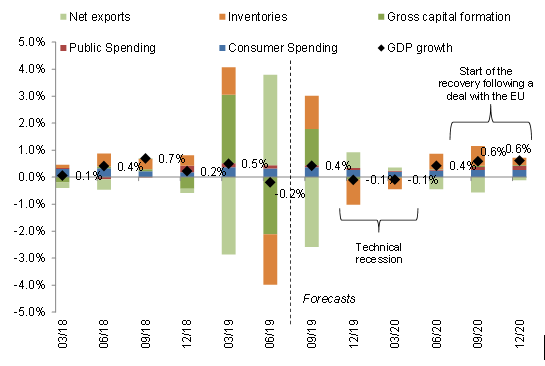

- In the short-term, the deal will not help the UK avoid a technical recession. In the medium-term, a soft Brexit (zero tariffs) would depend on a successful set up of the technical details related to the dual-customs system between Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The unwinding of contingency stockpiling will still shave off -1.5pp of real GDP growth over the next two quarters. Hence, we expect GDP to fall by -0.1% q/q in Q4 2019 and Q1 2020. A recovery is expected thereafter, with quarterly growth reaching +0.6% q/q on average in H2 2020. Higher volatility, with a limited rise in uncertainty, can be expected during the transition period, which should last until end 2021, after which growth should return to pre-referendum levels (+1.7%).

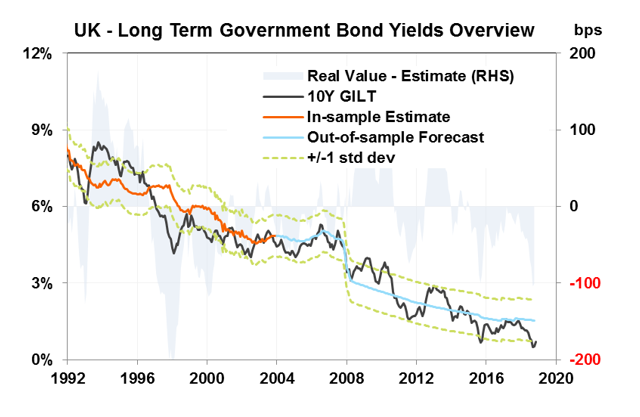

- What does this mean for markets? The deal, even with the ensuing technical extension, should be positive for the FTSE 250, which is domestically oriented (+5%). The sterling should continue its rally (1.20 vs the EUR by year-end) since it was almost the only Brexit risk barometer. Movements in long-term government bond yields should remain limited and temporary (room for a +40bp short-lived increase in the long-end of the rates curve). Despite the temporary volatility, the global ultra-low rate environment should keep the long-end of the UK gilts curve below fair value (1.5%).

- What does this mean for corporates? Lower uncertainty, given that the probability of a no-deal scenario has significantly reduced. We expect the rise in business confidence to boost domestic investment, which contracted over the past two years. Foreign investment should also gain momentum. Labor shortages should reduce and support corporates’ margins. For Europe, the cost of uncertainty (-0.2pp of real GDP growth per year) will slowly fade away but we expect a negative base effect on Eurozone exports due to frontloading of imports from the UK ahead of the previous Brexit deadline of 31 October.

An earlier-than-expected Brexit deal with Europe, but limited time for ratification could require a (short) technical extension. On 17 October, the European Commission and the UK government managed to agree on changes to the Withdrawal Agreement and the Political Declaration ahead of the EU Summit. The Heads of State need to approve it (likely) before it is ratified by the UK Parliament on 19 October (tough but not impossible as some Labor MPs could give support) and by the EU Parliament next week before the last day of its plenary session on 24 October (likely). With the limited time available, the UK government might be forced to ask for a technical Brexit extension until early 2020. Once the Withdrawal Agreement and the Political Declaration are ratified, the UK will kick-off of the 21-month transition period (until end of 2021). This will also see the start of negotiations on the future trade agreement with the EU, which is planned by both sides to be a “comprehensive and balanced Free Trade Agreement” that will “ensure no tariffs, fees, charges or quantitative restrictions across all sectors with appropriate and modern accompanying rules of origin and ambitious customs arrangements.”