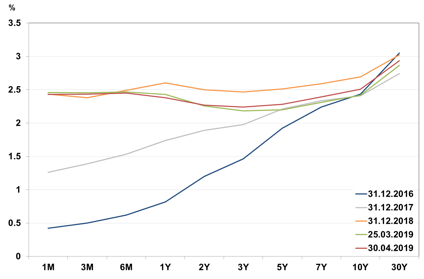

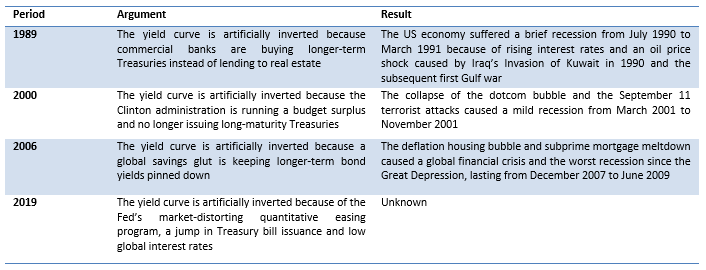

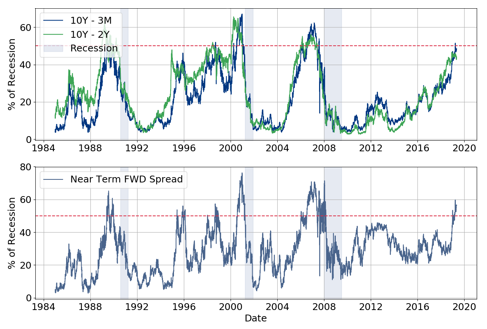

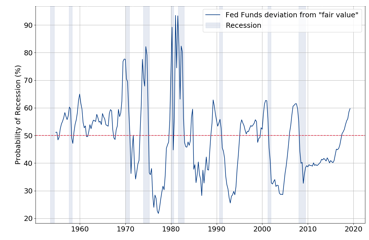

- In March 2019, the spread between the long and short end of the U.S. yield curve entered into negative territory, sparking concerns about an economic downturn ahead. For the past 60 years, each U.S. economic downturn has been preceded by a yield curve inversion. While some may argue that this time it is different, our calculations show that implied recession probabilities range between 43-60%, hinting towards a very likely economic correction in the near future. Timing is however unknown.

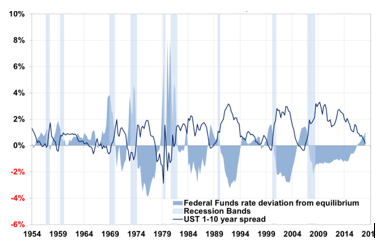

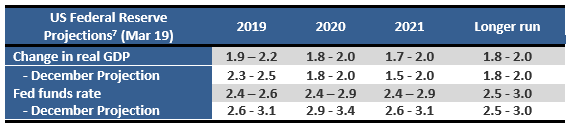

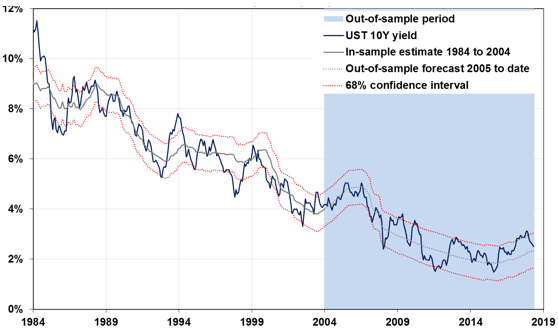

- Our long-term yields proprietary model shows that the current flat shape of the yield curve is likely to stay. Additionally, the current anchoring of the short end of the curve by the Federal Reserve at 2.5% plus the implicit stickiness of the long end of the curve, fairly valued at 2.5%, hints at the possibility of further yield curve inversion. The warning signs derived from the current and future shape of the yield curve suggest that a US economic downturn is probable. Investors need to look towards a downside risk-managing investment strategy.

Beware of the yield curve

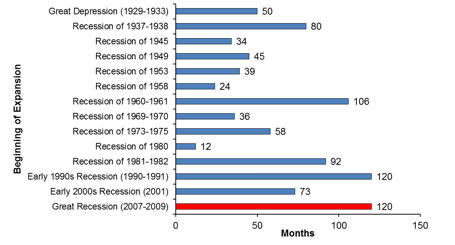

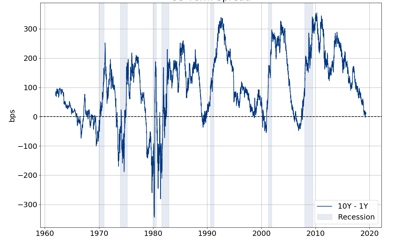

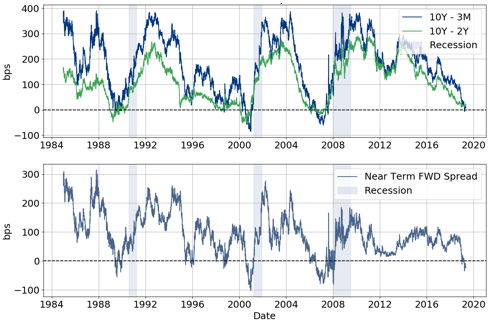

The US economy has just matched the longest cycle ever recorded in modern times (Figure 1). In this context, market participants are increasingly watching for a turning point, focusing on the inversion ofthe U.S. yield curve (i.e. when long-term treasury yields are lower than short-term treasury yields) as an indicator of the future economic outlook. For the past 60 years (earliest data point), an inversion of the yield curve heralded each economic downturn in the U.S. (Figure 2).

Figure 1: United States economic cycles