Executive Summary

- Record-high inflation in advanced economies is turning up the heat on central banks. With average wages set to rise significantly in 2022, they face a difficult choice: overlooking the overshoot to protect the post-Covid recovery or tightening quickly to stave off a potential wage-price spiral that would add fuel to the fire.

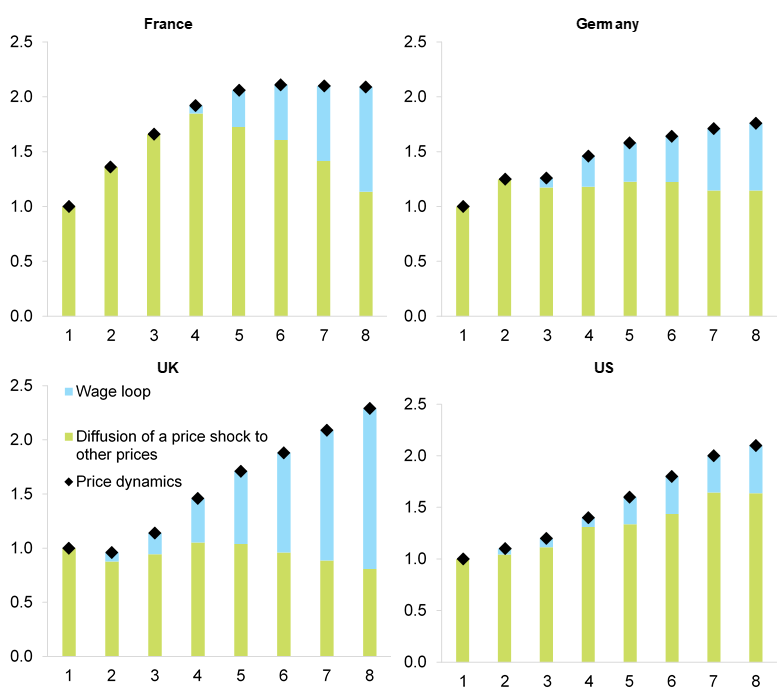

- While we expect inflation to recede by 2022 as pandemic-related disruptions ease, if we were to experience sustained rising prices, the UK and France could be most at risk of a wage-price loop materializing in end 2022 and 2023, respectively. We find that, in this risk scenario, the wage-price loop could push inflation up by +3pp in the UK and +1pp in France by end-2023..

Record-high inflation in advanced economies is turning up the heat on central banks. With average wages set to rise significantly in 2022, they face a difficult choice: overlooking the overshoot to protect the post-Covid recovery or tightening quickly to stave off a potential wage-price spiral that would add fuel to the fire. After having remained near zero over a decade, record-high inflation in advanced economies puts central banks under strong pressure to act. Due to buoyant demand and persistent supply bottlenecks, end-2021 (year-on-year) inflation reached a record high of 7% in the US but also 4.9% in the Eurozone, 5.6% in Germany, 5.1% inthe UK and 3.4% in France. After being concerned about “too low” inflation over the past decade, central bankers are now facing a new dilemma. Should they tighten monetary policy rapidly and strongly to revert an inflationary spiral with a looming wage-price loop? Or should they overlook the inflation overshoot for now to avoid tightening too early and too much, which could stall the recovery as the Covid-19 crisis turns endemic .

The interaction of goods and labor markets will play a key role in maintaining or amplifying the inflationary momentum. A wage-price loop is composed of two phases: First, the initial price shock being transmitted to wages, followed by a potential feedback effect from wages to inflation as firms adjust their prices to compensate for rising wages and costs.

Several factors set the stage for a wage acceleration in 2022: rising price pressures, the indexation of wage increases to inflation but also difficulties in recruitment (negative supply shocks or insufficient supply capacity to meet rising demand, eg. due to skill mismatches, limited geographic mobility and the structural transformation of the global economy after the crisis). Higher salaries to attract workers in tight sectors and composition effects (as low-skilled/less-productive workers who have lower salaries tend to lose their jobs first) will also come into play. In addition, the expected continued decline of unemployment rates (i.e. closing output gaps) will build upward wage pressures. In this context, stronger wage increases are more likely this time around compared to the period after the 2008 global financial crisis..

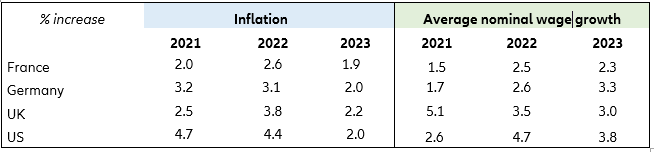

While we expect inflationary pressures to recede in the second half of 2022, stronger average wage growth is likely in the US (+4.7%) and the UK (+3.5%), while France and Germany should both see wage growth of +2.5% on average (Figure 1). In the US and UK, this reflects the greater flexibility of labor markets but also a changing labor force composition (declining share of low-wages during the sanitary crisis), the drop in the participation rate (especially in the US) and labor shortages (more pronounced in the UK after Brexit).

In France, wage growth will follow inflation in 2022 while in Germany it will be more moderate.The historical decomposition of our VAR analysis (see Appendix) shows that in France the moderation of nominal wages largely contributed to decceleration of inflation as of 2011, but the situation is likely to reverse with a significant cath up in wage acceleration, looking ahead. The quasi-generalized wage increase agreement in the French banking sector in 2022 –for the first time in 10 years – is one exemple among many others.In Germany, where wages tend to be negotiated in line with economic and productivity developments, there is less room for such a catch-up effect. After a decade of wage moderation under Harz IV reforms, nominal wages showed already a persistent and positive contribution to inflation dynamics in Germany as of 2011.

Figure 1 - Our baseline inflation and average wage increase projections (% increase y/y)