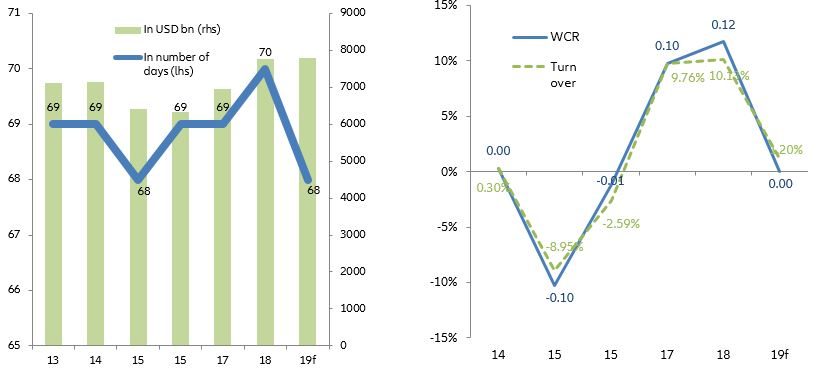

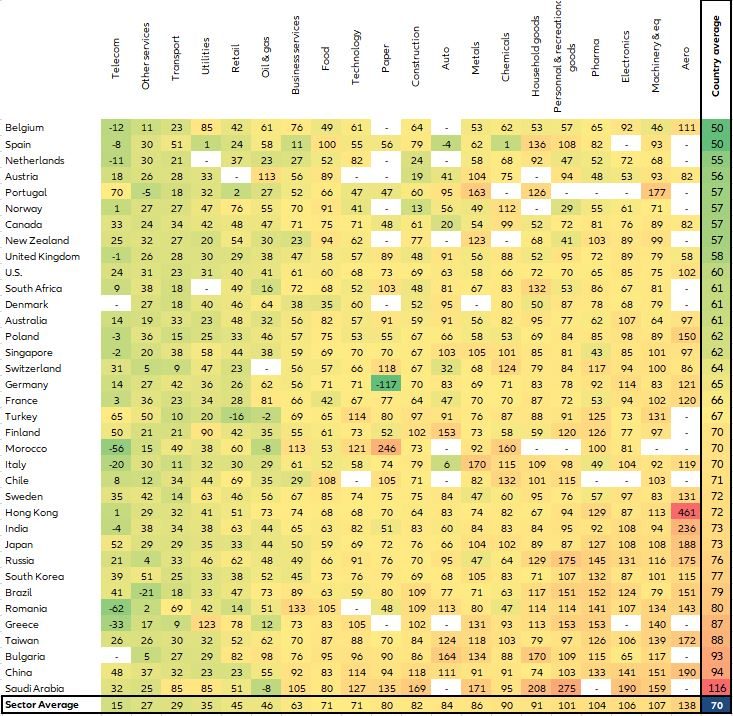

- At a global level, the Working Capital Requirement (WCR) of large companies - a measure of financial resources that companies consume to cover operating costs and expenses, and run their businesses efficiently – has deteriorated by +1 to 70 days in 2018, back to the highest (worst) level since 2012. In value terms, this represents a +12% rise i.e. +USD820bn of additional financial resources were consumed by working capital in 2018 - instead of supporting new product development, modernization, geographical expansion, acquisitions or debt reduction. For 2019, we expect a correction in inventories and a stronger discipline in payment in reaction to lower global growth and higher global uncertainty: this would support a decline in large companies’ WCR (-2 to 68 days).

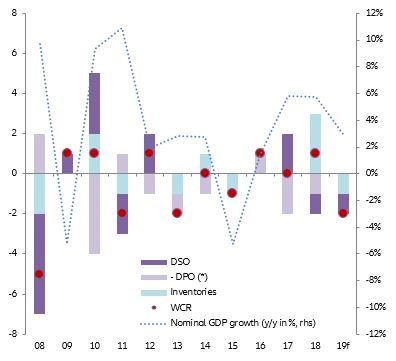

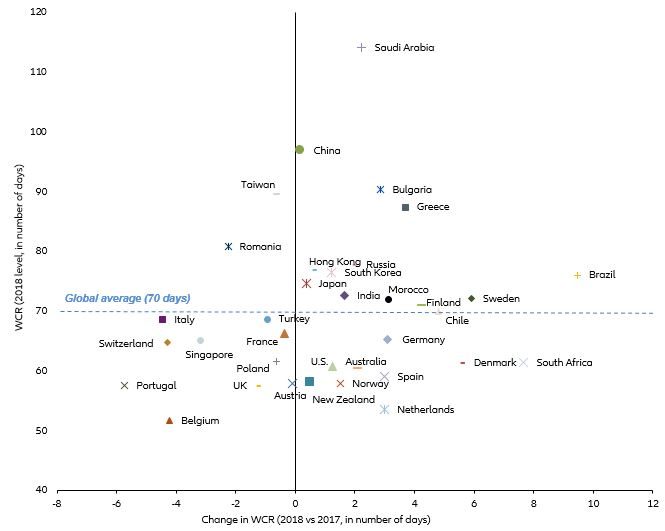

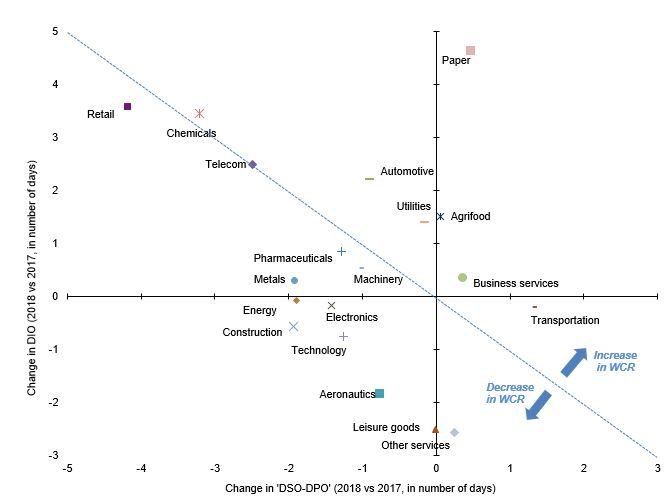

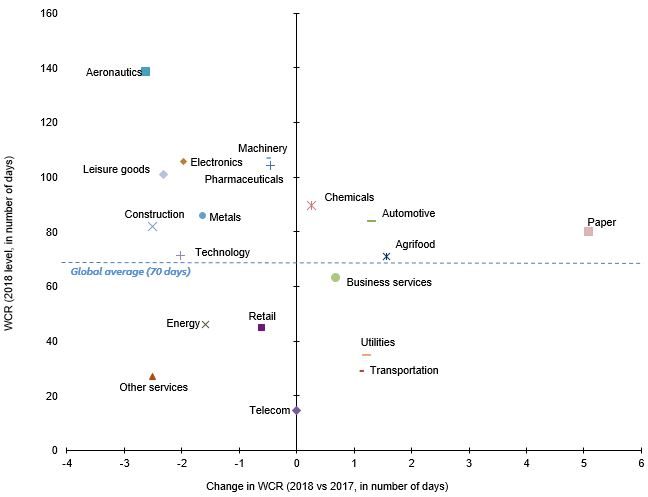

- Most increases in large companies’ WCR were recorded in emerging markets, notably Brazil (+9 days), South Africa (+8) and Russia (+2), - with China as the main exception and the surge in inventories as the key reason. This was accompanied by a strong increase in debt at end 2018: +1pp of GDP in emerging markets in Q4 2018 from the previous quarter. However, advanced economies were not immune, notably the U.S. (+1) and within Europe (+4 days for the Nordics on average, +3 in Germany and Spain). However, several other advanced economies stabilized or decreased their large companies’ WCR through a decrease in Days Sales Outstanding (Japan, the UK) or an increase in Days Payable Outstanding (Italy, France, Portugal). At a global level, the rise in WCR was concentrated in six sectors: agrifood, automotive, household equipment, paper, utilities and business services.

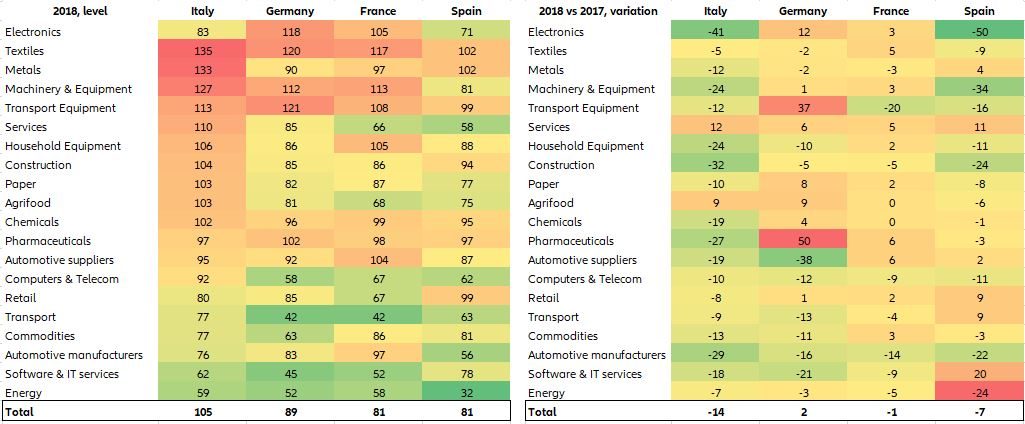

- Looking at Western Europe, Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs[1]) posted better performance in WCR than large companies in 2018. In Italy, SMEs reduced their WCR by -14 days (compared to -4 days for large companies). In Spain, SMEs recorded a -7 days decrease in WCR, while large companies posted a +3 days rebound. WCR slightly improved for French SMEs (-1 day), though it remained stable for large companies. In Germany, WCR for SMEs increased by 2 days and by 3 days for large companies. The highest increases in WCR were registered mainly in sectors which are dependent on external trade (in Germany: electronics, transport equipment, machinery and equipment, paper and agrifood; in France: electronics, textiles, pharmaceuticals and automotive suppliers).

- However, overall SMEs’ WRC remains one month longer compared to large companies. This is notably visible in Southern European countries, with a spread of 37 days and 22 days in Italy and Spain, respectively, against 23 in Germany and 15 in France. In those four countries, six sectors experienced higher than average WCR for their SMEs (105 days in Italy, 89 in Germany, 81 in France and Spain): textiles, transport equipment, machinery, metals, and, to a lower extent, chemicals and electronics.

Global WCR of large companies increased by +USD820bn in 2018

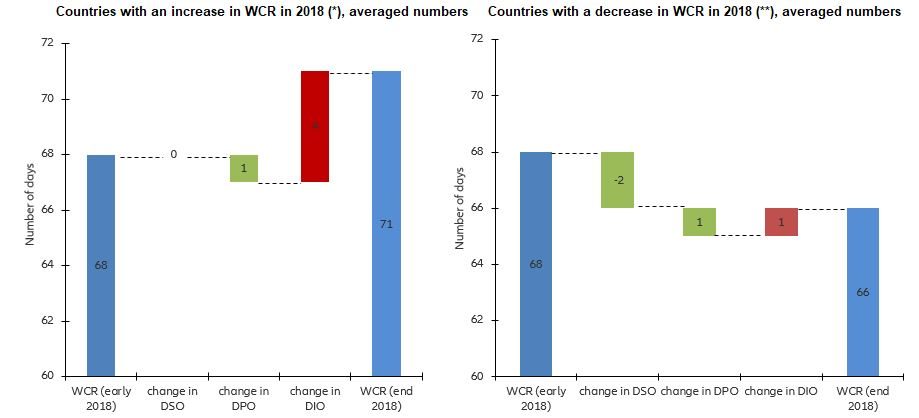

At a global level, the Working Capital Requirement (WCR) of large companies deteriorated by +1 day to 70 days in 2018, coming back to its highest (worst) level since 2012 and pointing to a lower operating cash flow, higher (debt) capital needs and lower profitability of companies. This rise in WCR mainly comes from inventories, which recorded an unusual accumulation (+3 days to 52 days in 2018), reaching a record high over the last 10 years. In the same period, large companies adjusted their payment behaviors by raising supplier terms of payment (DPO increased by +1 day to 47 days) and decreasing customer terms of payment (DSO declined by -1 day to 65 days), a double sign of “self-discipline”, alongside a weakening and uncertain economic outlook. Yet, those adjustments were insufficient to fully offset the accumulation of inventories. While their combined turnover rose by +10% in USD terms, large companies’ WCR reached USD7.8tn, which represents a +12% increase, i.e. +USD820bn of additional financial resources were consumed by working capital in 2018, instead of supporting major objectives such as new product development, modernization, geographical expansion, acquisitions or debt reduction.

For 2019, we expect a correction in inventories both in real terms (volume) and in book value (depreciation), as well as still stronger discipline in payment in reaction to lower global growth and higher global uncertainty, notably on the DSO side (-1 day). This would support a decline in large companies’ WCR by -2 days to 68 in 2019, leading to a stabilization of their combined WCR in value terms (at USD7.8bn) due to the expected increase in global turnover (+3% in USD terms).