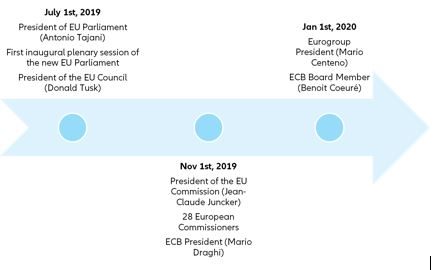

- In a few months, all the faces of Europe will change: the European Council President, the European Commission President and Commissioners, the European Central Bank President. These appointments will be impacted by the results of the May 2019 European elections, after which, for the first time in 40 years, a Grand coalition - spanning the European People's Party (EPP), the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) and the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe and Renaissance (ALDE & R) is needed to govern. Eurosceptic parties fell short – by a small margin – of a minority blocking representation (33.33%). The strength of the Greens (almost 10% of seats) suggests they will be the swing force. They could look to partner with mainstream parties in order to have a bigger say in the EU reform agenda. Given that a higher share of Green voters are under 30, mainstream parties could also be inclined to accept them, which could bring the governing coalition to more than two-thirds.

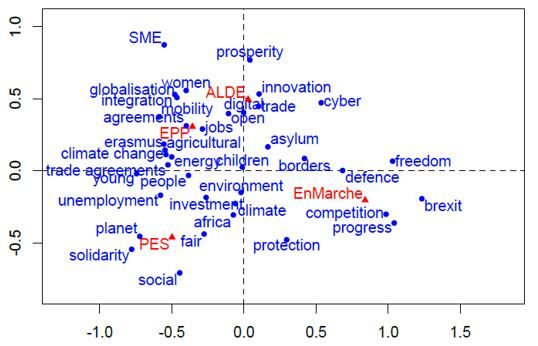

- Looking at the manifestos, we expect the newly formed Commission to focus on purchasing power and social policy; security, defense and climate change over the next five years. This three-party agenda could also be supported by non-traditional parties. On the other hand, business-friendly reforms, and bolder, yet dividing, policy blocks for Europe do not appear to be on top of the list.

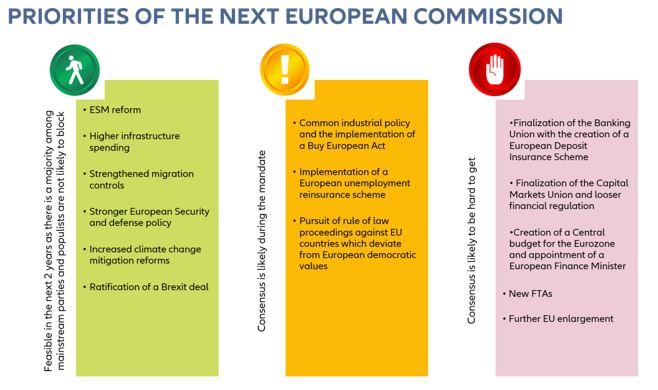

- When looking into the details, we identify three clusters of priorities for the next Commission:

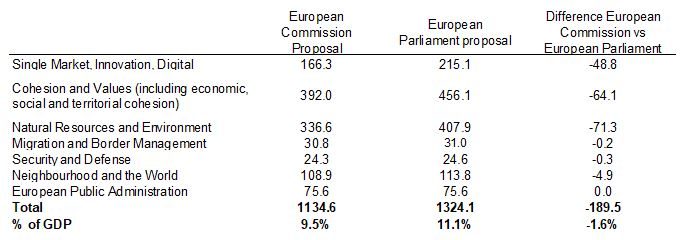

- First “easy breezy” topics which should get wide-ranging support in the first half of the 5-year mandate. This includes the reform of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM); higher infrastructure spending; strengthened migration controls; stronger European security and defence policy; increased climate change mitigation reforms and the ratification of a Brexit deal.

- Second, “mixed feelings” topics, which are not yet on the agenda but the US-China rivalry and mounting populism could help prioritize and get support in the second half of the 5-year mandate: a common industrial policy (CIP) including the Buy European Act, an unemployment reinsurance scheme, and proceedings against EU countries which deviate from European democratic values.

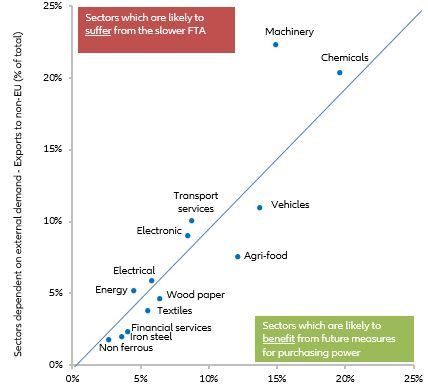

- Last, “hard-to-pass-without-a-miracle” topics during the 5-year mandate, in the context of a fragmented European Parliament: the European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS) allowing to finalize the Banking Union; the Capital Market Union (CMU) and less financial regulation; new Free Trade Agreements (FTA); a central budget for the Eurozone with a dedicated common Finance Minister and further EU enlargement.

A new political cycle

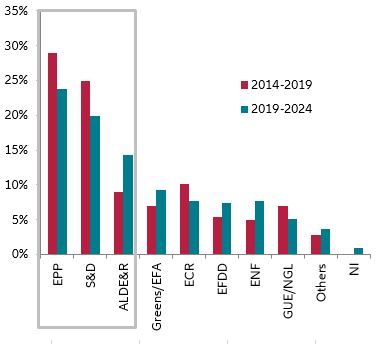

For the first time since 1994, over 50% of citizens voted in the European elections held in May 2019. But the results point to a fragmented EU Parliament, requiring a mainstream three-party Grand coalition to govern for the first time in 40 years, opening up a new political cycle. Hard populists won around 32% of the EU Parliament in the May 2019 elections, falling short of the blocking minority of 33.33%. Overall, hard populists (affiliated to parties) won less than 10 additional seats in the EU Parliament compared to 2014. But far-right parties are in the driving seat. As the current coalition (EPP + S&D) fell short of its absolute majority (44% of seats vs 54% in 2014, see Figure 1), a Grand coalition among the three mainstream parties which obtained most of the votes should be formed in the coming weeks (EPP + S&D + ALDE&R). Pro-European parties will have to cooperate much more closely to avoid a policy standstill in the years to come. The strength of the Greens (almost 10% of seats) suggests they will be the swing force as they are viewed as pro-Europe and social measures, but against new Free Trade Agreements, for example. They could look to partner with mainstream parties in order to have a bigger say in the EU reform agenda. Given that a higher share of Green voters are under 30, mainstream parties could also be inclined to accept them, which could bring the governing coalition to more than two-thirds.

Figure 1 – Distribution of EU Parliament seats by political group