- In 2020, the CFA Franc is turning 75 years old. The currency, used in two African regions, is backed by the French treasury and pegged to the Euro. Though the 2014 commodity price slump revealed vulnerabilities, the situation is not comparable with 1994, when the CFA Franc was devalued by -50% in Western (WAEMU) and Central (CEMAC) CFA Franc areas. Yet, divergence among members calls for cautious optimism about the stability of the currency.

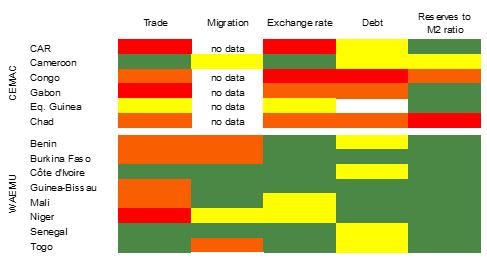

- Looking at today’s trade integration, mobility of the workforce, currency misalignment, debt sustainability and buffers of foreign exchange reserves in the zone (Optimum Currency Area criteria), we find that:

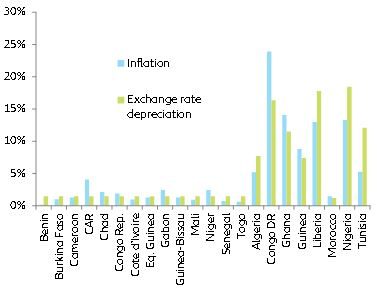

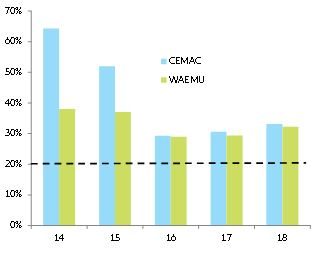

- The CEMAC area is under pressure. Our model shows intra-zone trade is -USD200mn below what common borders, language and currency should provide for. There is evidence of currency overvaluation in the region (mainly in CAR, Gabon and The Republic of the Congo) as a result of lower oil prices. This has led to an increase of public debt and a fall in the foreign reserves-to-M2 ratio below the 20% threshold in Congo Rep. and Chad. In spite of these fragilities, a breakup or devaluation in the next five years is unlikely. If oil prices were to fall to USD 30/bl for long, the area would not be able to avoid a devaluation, but a breakup will remain unlikely. CFA Franc membership is an institutional fix that grants price stability to its members. Any exit would be a political choice, not an economic one.

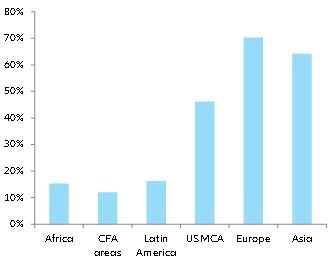

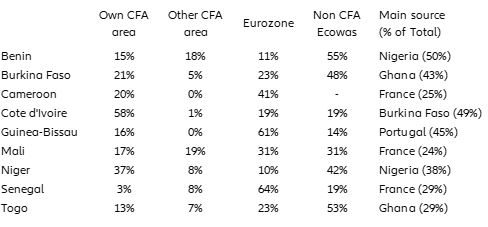

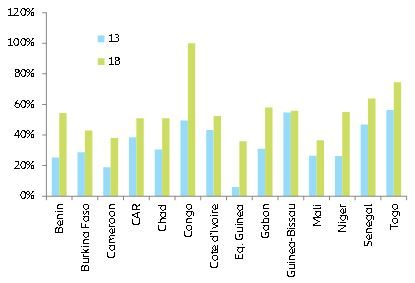

- The WAEMU area is under control. Public debt has increased but remained manageable, the CFA Franc parity does not look overvalued and the level of reserves is adequate. However, members are not making the most of the monetary union, since intra-zone trade flows look below what a monetary union would grant in five out of eight countries. The ECOWAS trade agreement and the ECO currency project with neighboring Anglophone countries like Ghana and Nigeria are game-changers. Yet, the CFA Franc may well celebrate its 100th anniversary before the ECO replaces it.

Does the CFA Franc still do the job?

The CFA Franc is a common currency arrangement established in 1945 that holds for two distinct areas in Central and Western Africa. Each area is organized through a fixed exchange with the Euro and a compensation account ruling that half of collective foreign reserves are deposited into the Banque de France.

Over the years, the arrangement allowed its members to avoid the recurrent depreciation pressures faced by peers (Ghana, Nigeria, for eg.) and to mutualize foreign reserves in order to use them when in trouble. While CFA Franc countries have performed better in terms of inflation stability, concerns have been raised as a result of lower commodity prices and (particularly for oil and metal exporters) lower growth since 2014. In this context, we analyze whether a significant depreciation of the CFA Franc is possible, and whether a breakup scenario is conceivable.

Obviously, exchange rate topics are often too sensational and things need to be examined with objective criteria. We propose in this paper to analyze the CFA Franc country members according to the following list of topics: Trade relationship, labor mobility, consistency of the exchange rate level, fiscal and debt convergence, and monetary convergence (See Figure 1 for summary).